Anne Brontë was just a baby when her mother Maria died, with her Aunt Branwell and her older sisters Maria and Charlotte becoming mother figures to her. There were two more women in the young Anne’s life however, and although they may not have been in regular contact they still played a significant part in her life: Anne Brontë’s godmothers, Elizabeth Firth and Fanny Outhwaite.

When Reverend Patrick Brontë moved to his new parish of Thornton, near Bradford, in May 1815 he had a wife and two daughters, Maria and Elizabeth, over the course of his nearly five years in the parish he would have four more children – Charlotte, Patrick Branwell, Emily and Anne.

Thornton, like their next parish of Haworth, wasn’t a straightforward parish – most of the inhabitants preferred the non-conformist Methodist and Baptist churches to the official Church of England, and resented having to pay taxes to the official church as they were then made to do.

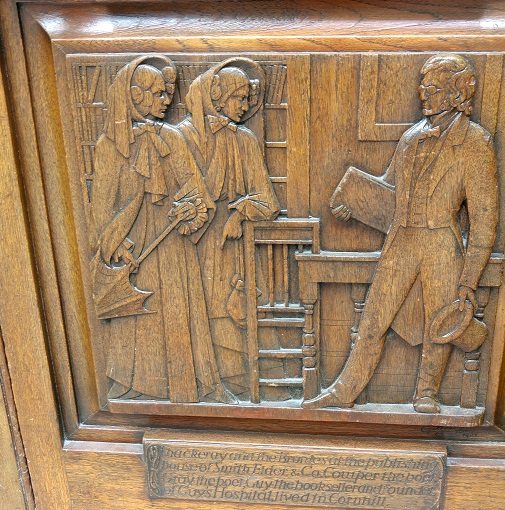

One Thornton family, however, made the Brontës very welcome – the Firths. The Firth family were the undoubted leaders of Thornton society, and lived at the imposing Kipping House to the south of the village, with a view looking over the moors (that’s a picture of Kipping House today at the top of this post).

By May 1815 there were only two Firths living there: John Scholefield Firth and his daughter Elizabeth, then aged eighteen. Mrs. Firth, also named Elizabeth, had died in a tragic accident a year earlier when she was thrown from a horse outside her home. John Firth was a doctor, but a man of considerable means, and he was a staunch supporter of the Church of England.

He saw it as a source of pride to regularly host the parish priest and his family, aided by his teenage daughter Elizabeth and from 1815 onwards his second wife Anne Greame.. Elizabeth Firth is of particular importance to Brontë lovers and researchers, because from the age of fifteen she kept a diary, detailing her daily activities. Many of them may seem mundane, for example one of her first entries is from 7th January 1812: ‘Miss Outhwaite went home’. From 1815 onwards however her diary becomes full of the Brontës: for example on 6th November 1817: ‘I went to Bradford with Mr Brontë. The Princess Charlotte of Wales died.’

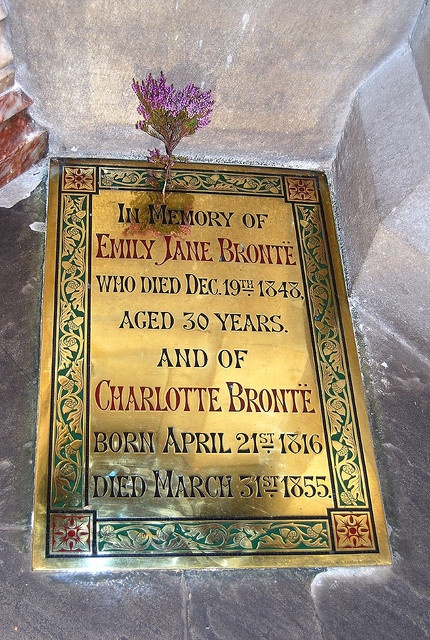

The diary doesn’t go into too much detail, but it shows the vast social intercourse between the Firth and Brontë family. She also volunteered as a teacher at Patrick’s Thornton Sunday school. One mark of the respect that Patrick, and his wife Maria, had for Elizabeth Firth is that they asked her to be godmother to their daughter Anne.

Although the Brontë family moved to Haworth shortly after Anne’s birth, they did keep in touch with Elizabeth Firth. We know that she visited Maria Brontë in Haworth during her long terminal illness, and that she took the elder Brontë children back to Kipping House with her for a while. By this time, Elizabeth had become mistress of the house, as her father died suddenly in late 1820, with Reverend Patrick Brontë by his side.

Elizabeth was now a relatively wealthy young woman, and three months after Maria Bronte’s death, Patrick visited her at Thornton. After his return to Haworth he wrote Elizabeth a letter proposing marriage. She rejected his proposal, and may have been angered by it as her diary records on 14th December 1821 that she had sent ‘my last letter to Mr Brontë’. Why was she angry? It may have been the age difference, at 24 she was twenty years younger than him, or it could have been the difference in social standing between them. She may have found his courtship unseemly so soon after the death of his wife. There was also the fact that she had her heart set on another, and she later married Reverend Franks of Huddersfield.

The break between Elizabeth and Patrick didn’t last long, and by 1823 they were reconciled, with Patrick visiting her in Thornton again.

The young woman mentioned in Elizabeth’s 1812 diary entry, Miss Outhwaite, also features heavily within them. Fanny Outhwaite had met Elizabeth at the exclusive Crofton Hall school near Wakefield, and they soon became best friends.

Fanny Outhwaite too was the daughter of a surgeon, Dr. Thomas Outhwaite. As a frequent visitor to Kipping House from her Bradford home, Fanny came into regular contact with the Brontës, and thus it was that in 1820 Patrick asked her to join Elizabeth as godmother to Anne Brontë.

The choice of these two young women as Anne’s godmothers showed that they were looked on approvingly from a moral point of view, but it was also a practical choice. They were both women who had considerably more money than most in the Brontë circle, and it seems likely it was hoped that they could make a financial as well as spiritual contribution to Anne’s life. They didn’t disappoint.

Patrick Brontë spent large sums of money on medical care, fruitless though it was for his dying wife, and ran up significant debts in the process. Elizabeth and Fanny were among the friends who cleared his debts. They made further contributions throughout the lives of all the Brontës, regularly sending them gifts. Elizabeth paid for the eldest Brontë daughters to attend Crofton Hall School, where she and Fanny had met, but they were there for just a term, Patrick seemingly realising that it would not do to ask Elizabeth to fund their whole school careers.

It was this that led to the fateful decision to send the Brontë girls to the much more affordable Cowan Bridge School, and Elizabeth Franks, as she then was, and her husband visited Maria, Elizabeth and Charlotte there in 1824.

Elizabeth and her husband lived close to Roe Head School, and in the summer of 1836 they invited Charlotte and Anne to spend the summer with them. The girls did this under duress, as they would much have preferred to be back at home in Haworth with Emily and Branwell. It was to be one of the last times that Anne would see her godmother, as in September 1837 she died at the home of the Outhwaites. A local newspaper reported that she died after ‘a protracted indisposition’, and so it may have been that she was being treated by Dr. Outhwaite.

Fanny Outhwaite herself died at the beginning of 1849. She too had remained in some sort of contact with the Brontes, and we know that Patrick visited her in June 1836 after she had broken her arm. She did not forget her goddaughter, and in her will she left Anne the sum of two hundred pounds: in that time a very substantial amount of money.

By that time, however, Anne Brontë too was dying. The legacy from her godmother allowed Anne to pay for her final trip to Scarborough, the resort that she loved and which was to witness her last breath on 29th May, 1849.

Patrick and Maria had made a good choice of godmothers for Anne. They were kind and caring, and provided financial support when needed throughout their lives, even if they couldn’t always be with her as much as they would have liked. Anne was a prodigious letter writer, even though only a handful remain, so it seems likely to me that she would have kept in correspondence with her godmothers. Maybe this is why Fanny Outhwaite remembered Anne so fulsomely in her will? Alas, any such letters have been lost to time. Elizabeth Firth’s diaries however have been preserved, and are now in the Sheffield University archives. A transcription of the diaries can also be read online right here, and they’re a useful and fascinating resource for Brontë lovers, as well as a fascinating glimpse into social history.