In last Sunday’s blog we took a first look at Aunt Branwell, revealing a woman who sacrificed much to step into the void left by her younger sister Maria’s death. Putting self aside she became a surrogate mother to the Brontë children, and by looking at her attitudes to them, and their attitudes to her, we can gain a bigger picture of what this dutiful Cornish woman was like.

The tragic death of her sister soon after Elizabeth Branwell moved to the Haworth Parsonage in 1821 meant that she found herself in an unfamiliar role: she was no longer just aunt to six young children, she had in effect become a substitute mother to Maria, Elizabeth, Charlotte, Patrick Branwell, Emily and Anne Brontë. It was a big task, but one that she was ready for.

As we saw last week, it’s easy to get a somewhat false impression of Aunt Branwell as being stern, cold, dogmatic, but if there is one word that truly sums her up it’s this: dependable. The Branwell family was a large one, and yet it seems that she was often the person that her siblings turned to and looked to. When we look at the weddings of the Branwells in Cornwall (a contemporary picture of Penzance is atop this page), one name keeps turning up as witness to the marriage: Elizabeth Branwell. When called upon by her siblings, she would always be there, and so it proved when Maria Brontë, nee Branwell, needed one of her sisters to fulfil the most important task of them all: taking her place after her death, and raising her children as she would have done.

When we look at Aunt Branwell’s relations with the Brontës one in particular stands out – it is quite clear that Aunt Branwell doted upon Anne Brontë, and that she loved her back. Ellen Nussey stated of Anne: ‘She was her Aunt’s favourite’, but why was this?

There are many possible reasons. One being that Elizabeth’s latent maternal instincts were roused by the helpless one year old infant Anne. It also must be remembered that Anne shared the same name as Aunt Branwell’s own dearly missed mother. Another possible reason is that Anne’s delicate features, clear complexion, lighter hair and blue eyes may have made her look more like a Branwell than her dark haired, brown eyed sisters.

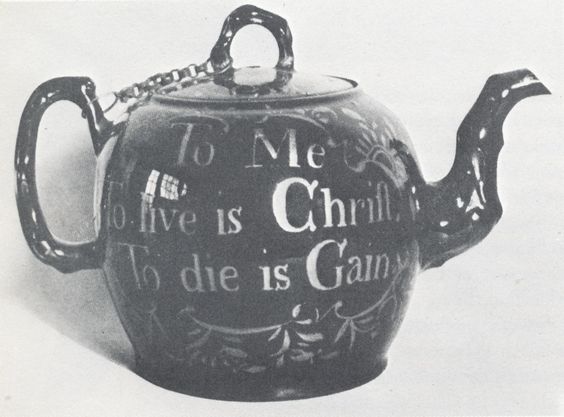

Aunt Branwell would have also found the infant Anne a blank canvas, a child to raise as she saw fit. They shared a bedroom for much of Anne’s time in Haworth, and it is to Aunt Branwell that we can attribute much of Anne’s deep seated religious faith, with its good and bad implications. Aunt Branwell was herself a very religious woman, with one of her prized possessions being a teapot on which is written: ‘To me to live is Christ, to die is gain’. On the reverse side is etched ‘William Grimshaw, Haworth’.

Grimshaw had himself been a predecessor to Reverend Patrick Brontë as Haworth’s parish priest, and he was also at the forefront of the new evangelical movement that grew within the Church of England in the mid 18th century. Along with the Wesley brothers he is one of the figures who helped to form Methodism. He became an immensely popular preacher, and so many would come to hear him that services had to be held on the wide open moors. He was also famous for the length of his sermons, and his hellfire delivery. It is said that he would go into the Black Bull Inn and whip people who were in there rather than attending his church.

It may be, then, that Aunt Branwell herself could be a bit of a Grimshaw like preacher – especially as the Branwell family had been pillars of the Methodist church in Cornwall. Certainly she would have seen the learning and interpretation of the scriptures as the most important subject of them all. Could this have seeped into Anne Brontë’s mind at an early age, and been one of the factors that led her to have a mental and physical breakdown when she was at Roe Head School? Anne struggled with dark thoughts of hell and damnation throughout her life, off and on, although she eventually conquered these doubts and fears thanks to her own belief in a loving God offering ‘universal salvation’. Whilst Aunt Branwell would have helped to form Anne’s religious beliefs, it’s more likely that the harsh and unbending preaching of Calvinist priests she heard, such as Reverend Carter at Mirfield, created Anne’s youthful breakdown.

Aunt Branwell could be exacting with the Brontë children, we hear how she made them carry out needlework lessons over and over again for hour on end, but for her it was a means to an end – she wanted to equip these children for the future lives as governesses and housewives that she thought awaited them. It must not be forgotten, however, that she was at heart a kind woman who did have a real affection for her nephew and nieces, and we do have evidence of this.

The references to a ‘mother’ in Anne’s Agnes Grey are without doubt references to Aunt Branwell, who she treated as her mother. Sharing a bedroom with her aunt gave her the love and security that she needed as a child, and that would create the kind and loving woman she grew into. In one passage of Agnes Grey, the heroin remembers:

‘In my childhood I could not imagine a more afflictive punishment than for my mother to refuse to kiss me at night: the very idea was terrible. More than the idea I never felt, for, happily, I never committed a fault that was deemed worthy of such penalty.’

Anne, like any girl, was not above talking back to her aunt or being mischievous on occasion however. In the 1834 diary paper Emily records such an incident:

‘Aunt has come into the kitchen just now and said ‘where are your feet Anne?’ Anne answered, ‘on the floor Aunt.’

Whilst putting an emphasis on needlework and bible studies, Aunt Branwell was also happy to indulge the love of reading that her nieces displayed, at a time when many people would have frowned on such an activity as being wasteful. We hear how at Christmas 1828 she gave the girls a book by Walter Scott entitled ‘Tales Of A Grandfather’. There could not have been a better present. It’s a collection of Scottish tales and folklore that Anne and her sisters loved, and its influence can clearly be seen in their youthful writings and especially in Emily Brontë’s ‘Wuthering Heights’.

Aunt Branwell, who had brought a legacy with her to Haworth, could also be called upon for financial support when needed. When the sisters were planning to start their own school, Charlotte turned to her aunt for support. Having already intimated that she would back them in this venture, Aunt Branwell was called upon again to fund Charlotte and Emily’s journey to Brussels. On 29th September 1841, Charlotte wrote to her (from Rawdon where she was at that time a governess):

‘You will see the propriety of what I say; you always like to use your money to the best advantage; you are not fond of making shabby purchases; when you do confer a favour it is often done in style; and depend upon it £50, or £100, thus laid out, would be well employed. Of course, I know no other friend in the world to whom I could apply on this subject except yourself.’

Aunt Branwell did indeed fund this trip, and she still offered to back Charlotte, Emily and Anne in setting up their school as well, although it was a dream that came to nothing.

There was to be one final gift from Aunt Branwell to four of her nieces. She died suddenly, and unexpectedly, on October 25th 1842, with Emily and Charlotte in Brussels. Anne was at Thorp Green Hall, and only Branwell was there. He was devastated, as he too had seen his aunt as a mother figure. He later wrote: ‘I have now lost the guide and director of all the happy days connected with my childhood.’

Here too we see how Aunt Branwell could be kindly and caring with the Brontës. As the only make she had held high hopes for Branwell, and he had become a favourite almost to the extent that Anne was. In latter years, however, she had despaired of his drinking and inability to secure a position for himself, but he would never forget the debt he owed her. Without this stabilising influence in his life, Branwell’s decline accelerated.

I have seen Aunt Branwell’s will, drawn up in 1833 and granted in 1842, which shares her estate valued at approximately £1500 between Charlotte, Emily and Anne Brontë, and also Elizabeth Kingston, one of the Brontë’s cousins in Penzance, who Aunt Branwell had presumably been concerned about. Anne was also left a gold watch and chain, and an eyeglass that we can imagine must have fascinated her as a child. Branwell Brontë was left nothing but a ‘japanned dressing case.’

The sums passed to these four girls were very considerable at the time, and we have this legacy largely to thank for the Brontë novels that we all love today. It alleviated the immediate necessity for them to take any job, any source of income. It also provided the funds that the sisters used to pay for the publication of their first book: ‘Poems by Currer, Ellis and Acton Bell.’ This book was far from an instant success, but it led directly to Agnes Grey, Wuthering Heights, and Jane Eyre.

In Agnes Grey, the eponymous heroine eventually founds a school alongside her kind, wise and resilient mother. This is Anne Brontë’s final tribute to Aunt Branwell, a woman she loved and who loved her back just as a mother would have.

Really interesting The Cornish influence of Aunt Branwell may also have inspired Anne’s love of the sea and its emotive and spiritual powers I think their is more Cornish and Methodist influence in Anne than people realise