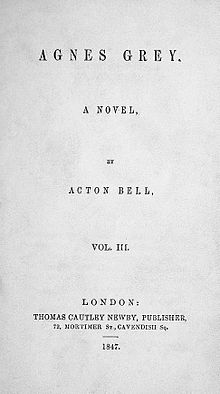

The beginning of December 1847 was a time of great excitement in the Brontë Parsonage at Haworth, but it was nothing to do with the impending arrival of Christmas; it was the month that saw the joint publication of Agnes Grey, by Acton Bell, and Wuthering Heights, by Ellis Bell, and the gestation of these great novels had been anything but smooth.

Of course, we know these writers better today by their real names of Anne Brontë and Emily Brontë, rather than the pen names that they, together with their sister Charlotte who masqueraded as Currer Bell, adopted to keep their identities and gender secret. They had been writing both prose and poems together since their childhood, at that time in conjunction with their brother Branwell although by the time 1847 came around he was too lost to alcohol and opium to even realise that his sisters were writing let alone collaborate.

Whilst Agnes Grey, the first of Anne’s two novels, was introduced to the public at the end of 1847 its origins were earlier, possibly much earlier. In September 1845, Charlotte had discovered, although of course we’ll never know how ‘accidental’ the discovery was, a hidden book of Emily’s poems. After a bitter argument, the three sisters eventually agreed to publish a collection of their poetry, which came out in 1846 as ‘Poems by Currer, Ellis and Acton Bell‘. Although this wasn’t a commercial success, it seemed to galvanise the Brontë sisters and they realised that what had long been a hobby could, even if ever so slightly, possibly be a way to earn an income for themselves. They quickly decided to write a short novel each, and submit them for publication together – the three volume format of novels being then a publishing norm.

Agnes Grey and Wuthering Heights were accepted for publication by Thomas Cautley Newby in mid 1847, but Charlotte’s contribution of The Professor was rejected by all who saw it meaning that it would be Anne and Emily’s novels that would be published together. We know, however, that Agnes Grey was actually completed by May 1846 and an earlier version of it was possibly being worked on in 1845 as she notes in that year’s diary paper that ‘I have begun the third volume of “Passages In The Life Of An Individual”, I wish I had finished it.’

It seems likely that ‘Passages In The Life Of An Individual’ was the original version of what became ‘Agnes Grey’, and so she had been writing a novel at least a year before the sisters’ joint plan was formally hatched. It’s also likely that she had been collecting material for the novel since as early as 1839 when she became a governess to the Ingham family of Blake Hall, Mirfield, as this family, and Anne’s less than pleasant time with them, is recreated faithfully in her depictions of the Bloomfield family in Agnes Grey. Her time as governess to the Robinsons is also replicated in many ways in her depiction of the Murrays in Agnes Grey.

Whilst being a beautiful read in its own right, and a fascinating glimpse at the life of a nineteenth century governess, Agnes Grey is in many ways autobiographical, although we do of course have to be careful to sift the fact from the fiction. An example of this is found on the very first page where Agnes proclaims: ‘My father was a clergyman of the north of England; deservedly respected by all who knew him.’ This is also something that Anne herself could have proclaimed. Agnes Grey is an oft, and very unfairly, overlooked book, but in my opinion it’s one of the true masterpieces of English literature: it’s short and sweet, with not a word out of place. In the first half of the twentieth century, the Irish novelist George Moore called Agnes Grey: ‘the most perfect prose narrative in English letters.’ I share that view.

Anne and Emily must have been very excited when Newby signed up their book, but things didn’t progress smoothly from that point on. When they received the proofs they were disappointed to find that they contained many errors, and later they would find that many of their corrections had also been omitted. Worse than that, there was no firm indication of when, if ever, the books would see the light of day. Thomas Newby was a businessman more than a book lover, and he would only publish something if he thought he could make a healthy profit on it, but an event was about to occur that would force his hand.

Charlotte Brontë, although initially disheartened by the failure of The Professor, did not give up. She swiftly wrote another book and sent it to a publisher, Smith, Elder & Co., who had been slightly encouraging to her. The book, as we all know, was Jane Eyre and the publishers instantly realised what they had. They signed Charlotte and her novel up immediately, and it was published and distributed in record quick time. In October 1847, less than two months after Charlotte had speculatively sent her manuscript to London, it was being devoured by the public.

Jane Eyre was a huge and rapid success, and readers were already eager for more by this new young writer Currer Bell. Thomas Cautley Newby noticed what was happening, and decided that now was the perfect time to release the books that he had by what he thought were the two other Bell brothers.

Thus it was that Agnes Grey and Wuthering Heights were finally published in December 1847, designed to ride upon the coat tails of the already published and successful Jane Eyre which had been written a year after the novels by Anne and Emily. Newby was an unscrupulous man, and he tried every trick he could to indicate that both Agnes Grey and Wuthering Heights were both by Currer Bell, Jane Eyre’s author. When he tried the same trick with Anne’s second novel, The Tennant Of Wildfell Hall, the sisters could take no more and Charlotte and Anne were stung into action and a trip to the bright lights of London which would have unforeseen results for the whole family.

Nevertheless, December 1847 must have been a very happy time for Anne, Emily and Charlotte Brontë. They had achieved their objective, and these obscure young women living on the edge of the Yorkshire moors were all now published authors. Who knew what successes lay ahead of them, these three sisters with the world at their feet and dreams of happiness? We can leave them there smiling and laughing around their dining table, for as Christmas 1847 loomed it was perhaps kinder that they didn’t know that within a year Branwell and Emily would both be dead, and Anne mortally ill.

I have a copy of “Wuthering Heights and Agnes Grey” published by Curl Brothers in Norwich. There is no date in the book. Can anyone give me more information or tell me where to find it?

Thank you.