Anne Brontë prized honesty above all other qualities, and her writing was a quest for the truth, so when she felt her integrity called into question she sprang into action. The result was the ‘Preface to the Second Edition of The Tenant Of Wildfell Hall’, and it’s not at all as dry as the title makes it sound. It contains anger, indignation, and pride in equal measures; it is a manifesto outlining all that Anne Brontë believed in, and it’s beautiful, powerful, and moving by turns. It is, in short, unlike anything else in the Brontë canon.

The catalyst for its creation was a series of reviews that followed the publication of both Agnes Grey and The Tenant Of Wildfell Hall. Critics had said that they seemed too wild and unreal, that they dealt with subjects that were not fitting for modern novels, that they were morally lax and even ungodly. The Spectator said the author had ‘a morbid love of the coarse, not to say of the brutal’. The Rambler intoned, ‘The scenes which the heroine relates in her diary are of the most disgusting and brutal species.’

Indifference to her books Anne could take, after all people had been indifferent to her throughout her life, but these accusations cut her to the bone. ‘If you cut me do I not bleed?’ the merchant of Venice famously said, and Anne was to bleed over the three pages of her preface.

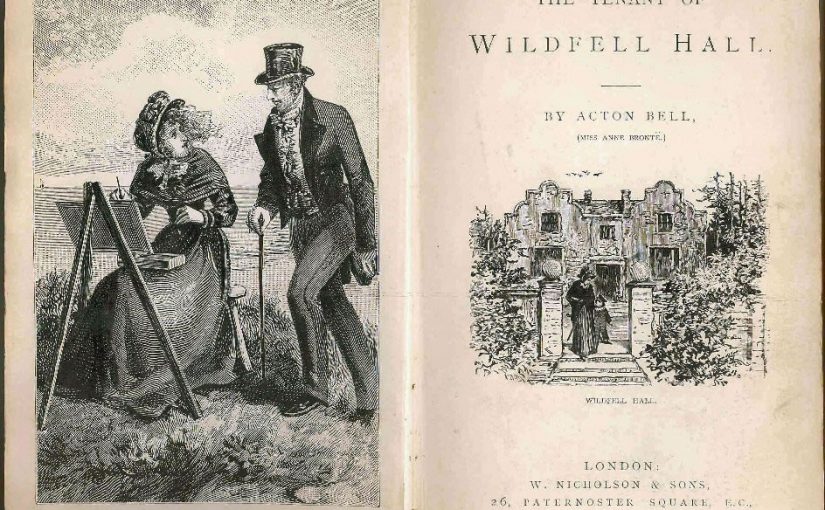

A measure of Anne’s insistence on honour is shown by her swift action when she found that her publisher, Thomas Newby, had wrongly been telling people that she, or rather Acton Bell as he knew her, was also the author of Jane Eyre. Within twenty four hours of the letter arriving, she and her sister Charlotte Brontë were in London to confront their respective publishers. Charlotte no doubt expected Anne to break off her contract with Newby and turn instead to her publisher Smith, Elder & Co. Anne, however, would not turn her back on a contract she had signed, but instead insisted on Newby publishing a preface to the second edition being planned for The Tenant Of Wildfell Hall in which she would refute some of the accusations being made against her. It was to become her personal manifesto, as well as the last piece of prose she would ever have published. Anne Brontë would now speak with her own voice, as if she knew she was running out of time, on subjects close to her heart:

On the importance of truth in writing: ‘My object in writing the following pages, was not simply to amuse the Reader, neither was it to gratify my own taste, nor yet to ingratiate myself with the Press and the Public: I wished to tell the truth, for truth always conveys its own moral to those who are able to receive it.’

On the proper subject of fiction: ‘If I can gain the public ear at all, I would rather whisper a few wholesome truths therein than much soft nonsense.’ (This has sometimes, wrongly, been taken as an attack on Wuthering Heights, but it is instead a rebuttal of critics who said that the vérité scenes of her novels were not a fitting subject for literature.)

On the didactic power of literature: ‘When we have to deal with vice and vicious characters, I maintain it is better to depict them as they really are than as they would wish to appear. To represent a bad thing in its least offensive light, is doubtless the most agreeable course for a writer of fiction to pursue; but is it the most honest, or the safest? Is it better to reveal the snares and pitfalls of life to the young and thoughtless traveller, or to cover them with branches and flowers? O Reader! if there were less of this delicate concealment of facts – this whispering ‘Peace, peace,’ when there is no peace, there would be less of sin and misery to the young of both sexes who are left to wring their bitter knowledge from experience.’

On the perfect work of art: ‘I love to give innocent pleasure. Yet, be it understood, I shall not limit my ambition to this – or even to producing ‘a perfect work of art’; time and talents so spent, I should consider wasted and misapplied.’

On being misunderstood by critics: ‘When I feel it is my duty to speak an unpalatable truth, with the help of God, I will speak it, though it be to the prejudice of my name.’

On the true identity of the Bells: Respecting the author’s identity, I would have it be distinctly understood that Acton Bell is neither Currer nor Ellis Bell, and therefore, let not his faults be attributed to them. As to whether the name be real or fictitious, it cannot greatly signify to those who know him only by his works.’

On the equality of the sexes: ‘All novels are or should be written for both men and women to read, and I am at a loss to conceive how a man should permit himself to write anything that would be really disgraceful to a woman, or why a woman should be censured for writing anything that would be proper and becoming for a man.’

Anne was an experienced and usually rapid writer, but days turned into weeks as she wrote this preface. She would delete lines, tear up pages, until she was satisfied that everything she said was just how it should be. This, after all, was Anne Brontë presenting her true self to the world: honest and truthful, courageous, bold, and not the downtrodden, quiet woman some people still think of. Today, increasing numbers are finding that her books may be set nearly two centuries ago, but they speak to us in a very modern way, and with an understanding that few other Victorian novelists have achieved.

I think Anne would have been proud of the impact her novels continue to have, and delighted at the praise she is now finding. I myself want here to give thanks for all the kind words people have given me regarding my biography of Anne, ‘In Search Of Anne Brontë‘. From a glowing review in The Mail On Sunday, to praise from readers on both sides of the Atlantic, it means so much to me, and I hope it introduces Anne Brontë to even more readers.