As we reach the last days of May, my thoughts always turn to a seaside town on the east coast of England – Scarborough. It was there that Anne Brontë laid down her pen on 28th May, 1849.

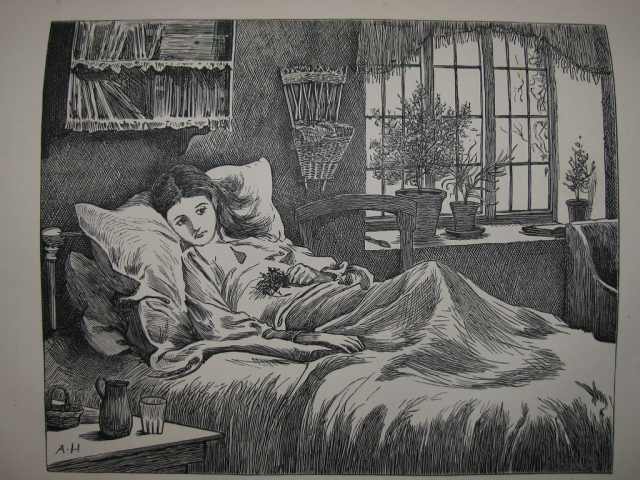

Anne had been diagnosed with consumption, what we today call tuberculosis, by a Leeds Doctor named Teale in January of that year. It was the disease that had already killed her eldest sisters Maria and Elizabeth, and within the last few weeks and months had also claimed the lives of Emily and Branwell Brontë, so Anne knew that there was little hope. Nevertheless, after the initial shock abated, Anne determined to try all she could to be cured, or at least to prolong her life. A succession of medicines were tried, including ‘Godbold’s Vegetable Balsam’ but to no avail; Anne complained that they tasted of train oil, and eventually found herself unable to swallow them.

One potential help remained, at least in Anne’s mind. She had visited Scarborough annually during her days as governess to the Robinson family, and had seen people who were convinced that the town’s spa waters had cured them of their ills. With this in mind she begged Charlotte, and then their mutual friend, Ellen Nussey to accompany her to the resort that she loved. Reticent at first, it soon became clear that it was Anne’s only hope.

They arrived in Scarborough on 25th May, and took rooms at Wood’s Lodgings, number 2 The Cliff, where the Grand Hotel stands today. Anne’s final days were filled with love, faith and courage – a perfect reflection of the 29 years that had come before them. Shortly before two on the Monday afternoon of the 29th, Anne turned to her sobbing sister and encouraged her to: ‘Take courage, Charlotte, Take courage.’ They were her well known last words, but just what happened after the death of Anne Brontë?

Charlotte Brontë’s mind must surely have travelled back to Haworth a year earlier, when three sisters were sat happily around their dining room table discussing books and poetry. Now she was the only one of six siblings left, and the depression she suffered from throughout her life descended again. In this circumstance it probably fell upon Ellen Nussey to make the funeral arrangements, and one question that needed answering was whether Anne should be buried in Scarborough or in Haworth with her family.

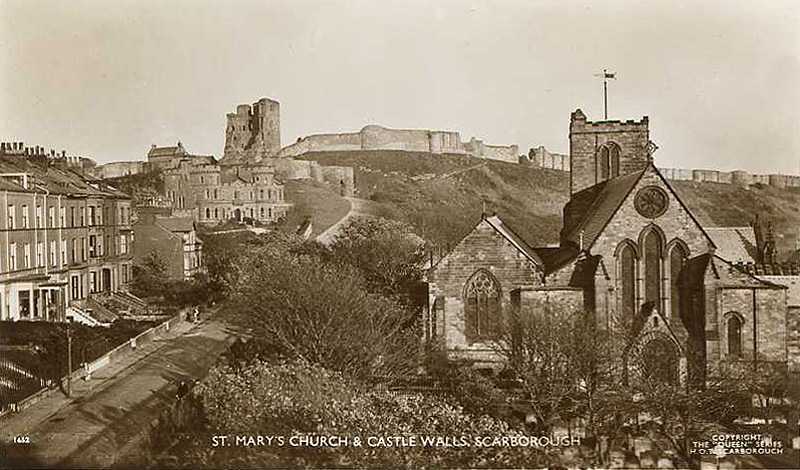

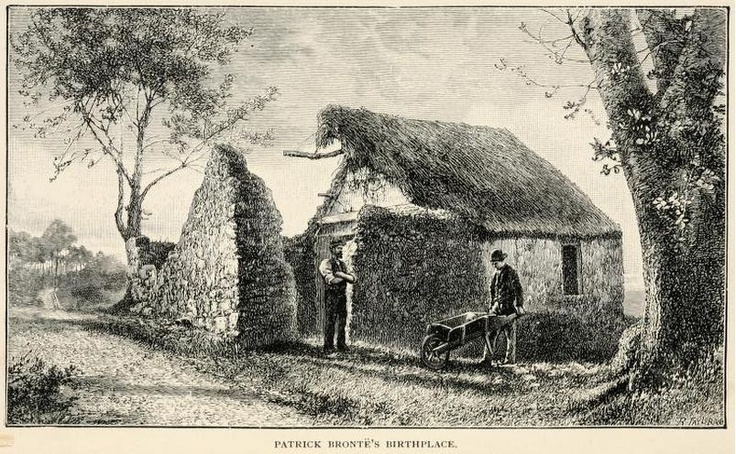

Anne’s love of Scarborough was taken into consideration, as was the burden a Haworth burial would place upon Patrick Brontë – by now 72, and having seen two of his children buried in the last year. He would later confess that as he watched the carriage carry Anne away from Haworth on 24th May, he knew he would never see her again. The decision was made to bury Anne in Scarborough – and she now rests in the graveyard of St. Mary’s church. She lies in the shadow of Scarborough Castle, and below her is the sea. It is a view Anne would have loved, and in fact it is next to the very spot where Weston proposes to Agnes Grey at the climax of her first novel.

If you visit Anne’s grave, and I like to visit and leave flowers whenever I can, be aware that Anne is not in the main churchyard, but in a smaller annexe to the side of this which now also houses a car park.

Anne’s funeral service did not take place at St. Marys, as it was being renovated at the time. The service instead took place at Christ Church on nearby Vernon Road, a building no longer standing, on 30th May. The Doctor who had examined Anne in her final hours was so impressed by her conduct that he offered to attend her funeral service. Indeed, he told Charlotte that: ‘in all his experience he had seen no such death-bed, and that it gave evidence of no common mind.’ Another indication of Anne’s calmness at her death is that the maid, Mrs Jefferson, brought food for the guests, little realising that Anne had passed away.

Charlotte and Ellen thanked the doctor, but said his presence would not be needed. The funeral service would be a quiet, personal affair with only her sister and friend in attendance. As they entered Christ Church on the Wednesday, however, they found this was not to be so – somebody else was already waiting for them.

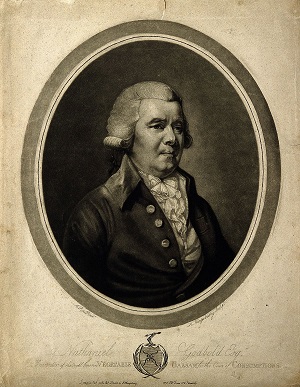

The unexpected, yet welcome guest, was the kindly Margaret Wooler. Just 12 years earlier she had presented the young Anne with a medal for good conduct at her Roe Head School. Now with a home in Scarborough, she had come to pay the last respects to a former pupil, and to comfort another former pupil and employee, Charlotte.

We do not know how Miss Wooler knew of the funeral; it could be that Charlotte or Ellen, knowing that she was nearby, had written to her or visited her, or it could be that she had seen a notice of the death in a local paper. It could even be that Miss Wooler was not in Scarborough at the time but travelled there purposely for the funeral, as she had earlier offered her home for the use of Anne and Charlotte while they were in Scarborough, saying she would be away in May. However she came to be at Christ Church it was a kind thing to do, and typical of the woman who five years later would give Charlotte Brontë away at her wedding.

A letter was sent to Haworth informing Patrick of the death of his daughter, and with his concern now for his only surviving child he wrote back to Charlotte urging her to spend some time at the coast recuperating before returning to Yorkshire.

As she revealed in a letter to W.S.Williams (of her publisher Smith, Elder & Co.) on 13th June, Charlotte now found Scarborough too happy and cheerful for these days of mourning, and so after a further week in the resort she sent Ellen home and journeyed on alone to Filey and then Bridlington.

Charlotte could not bring herself to return to Scarborough for another three years, and even then she based herself once more in Filey. Upon visiting Anne’s grave, for the first and only time after her funeral, she was shocked to find that there were five mistakes on her gravestone.

These mistakes were presumably a result of the memorial being arranged by Ellen, and an indication of Charlotte’s state of mind when it was being prepared. We do not know what four of the mistakes were, as Charlotte paid to have them corrected – the spelling of the name is one obvious mistake that could have been made. One mistake famously remained uncorrected, however. Anne’s gravestone now is weathered and beaten by the salt air, rain and sea frets of Scarborough, but you can still make out that it says Anne died aged 28, when she was in fact 29. A memorial that Charlotte had installed in Haworth’s church, no longer there, fared no better as it stated that Anne died aged 27.

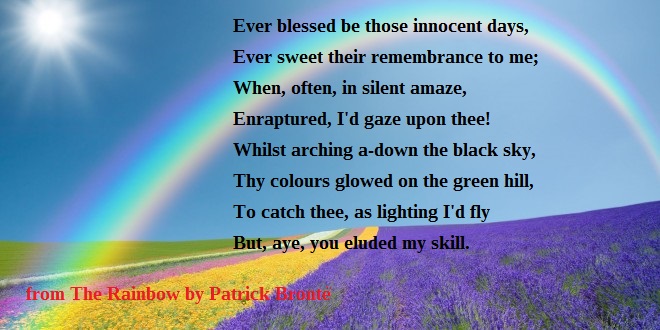

May 29th is a sad day for Anne Brontë fans across the globe. Whether we are in Yorkshire or New York, Scarborough or Sydney, we can all take a moment to reflect on the courageous end of this brilliant writer. We should not dwell on sad thoughts however; to Anne, death was just the beginning of a more glorious existence. She would want us to be happy and courageous, just as she wanted Charlotte and Ellen to be so. Therefore, let us instead open one of her wonderful books, and celebrate the life and genius of this wonderful woman.