Anne’s brother Branwell Brontë was the great hope of the family – from his birth in June 1817 there was a weight of expectation on his shoulders: he it was who would take the family name into the world, he also who would help to provide for his sisters after his father’s death, if they themselves had not started a family of their own by that time. Of course, things didn’t quite work out like that.

Branwell is a man who strongly divides opinion today: some see him as an unrecognised genius, whereas to others he is the villain of the Brontë story who cared about nothing but his won gratification. The truth lies in neither of these extremes; he was a human being with frailties like all of us, but his frailties overpowered him. Francis Leyland, who knew him well and became his chief post-mortem defence counsel, perhaps put it best when he wrote:

‘Patrick Branwell Brontë was no domestic demon – he was just a man moving in a mist, who lost his way.’

On the other hand, Leyland did not see Branwell’s daily life at Haworth Parsonage, where he could indeed wreak havoc, and frequently did: inadvertently setting his bed on fire, having screaming fits at night, and threatening to kill his father are just some of his actions.

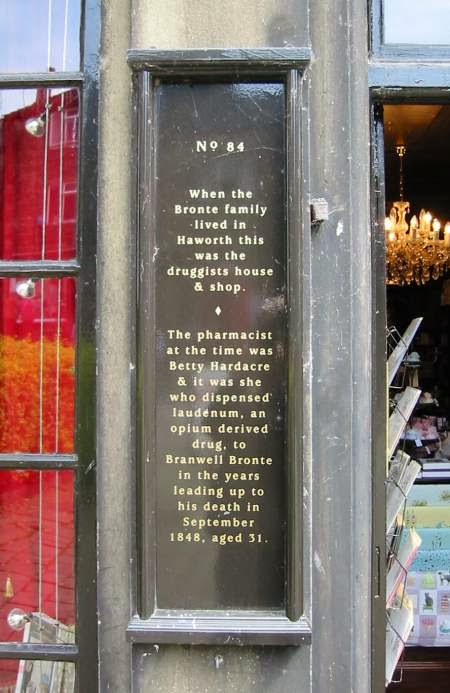

It is easy to judge Branwell harshly, but he was fighting demons from a young age. The death of his mother and beloved eldest sisters had a profound impact upon him in his early years, and his later actions speak of one who was suffering from a mental illness. Certainly, his addictions to alchohol and then opium did little to create much needed equilibrium in his life.

Towards the end of his life, aged just 31, he cut an increasingly pathetic figure, so that he we see him hunched over in the street sobbing pitifully and unable to raise his leg to climb a single step, and we witness him brandishing a knife, mouth quivering uncontrollably, because he thought he was going to meet not his friend Francis Grundy, but Satan.

Nevertheless, his death on 24 September 1848 came suddenly, and suprisingly he died not as a result of his addictions but of chronic marasmus (wasting) due to tuberculosis. It was the forerunner of the disease’s eight months reign of terror that would also snatch Emily and then Anne.

Charlotte Brontë was particularly devastated by her brother’s death. They had been incredibly close in childhood, inventing the kingdom of Angria together and producing the first of the Brontë’s little books that are marvelled at today. She was unable to accept his failings however, and in his last two years they did not speak. Now it was all too late.

Her letter to W.S. Williams after Branwell’s death revealed that she did at least find some comfort in the manner of her brother’s death:

‘I myself, with painful, mournful joy, heard him praying softly in his dying moments, and to the last prayer which my father offered up at his bedside, he added “amen”. How unusual that word appeared from his lips – of course you who did not know him, cannot conceive. Akin to this alteration was that in his feelings towards his relatives – all bitterness seemed gone… all his vices seemed nothing to me in that moment; every wrong he had done, every pain he had caused, vanished… He is at rest, and that comforts us all – long before he quitted this world, life had no happiness for him.’

In his dying moments Branwell became a penitent, and this comforted Charlotte who in turn was herself now penitent. Anne Brontë, on the other hand, had always loved her brother, even finding him a job as governor at Thorp Green Hall when his prospects seemed bleak. That move, of course, went disastrously wrong, but Anne would never judge Branwell harshly. She believed in forgiveness, and forgiveness time after time if needed. This view was expressed long before Branwell’s death, as if in a presentiment of it, in her poem ‘The Penitent’, with which we close today’s post:

‘I mourn with thee, and yet rejoice

That thou shouldst sorrow so;

With angel choirs I join my voice

To bless the sinners woe.

Though friends and kindred turn away,

And laugh thy grief to scorn;

I hear the great Redeemer say,

“Blessed are ye that mourn.”

Hold on thy course, nor deem it strange

That earthly cords are riven:

Man may lament the wondrous change,

But ‘there is joy in heaven!’