Today is Remembrance Sunday, a time not to glorify war but to remember them, and the people who lost their lives in them and who were willing to risk everything for a cause they believed in. Of course, British people have been involved in conflicts of one kind or another for century after century, and so in today’s post we’ll look at the Brontë’s attitudes to war, and at a couple of heroes within their own family – one of whom made the ultimate sacrifice.

The Brontë children were born as the era of the Napoleonic wars was coming to an end, with Charlotte Brontë born a year after the pivotal battle of Waterloo that on 18th of June 1815 saw the forces of the Duke of Wellington, and his Prussian allies under Blucher, defeat once and for all the tyrannical Napoleon Bonaparte. Today it is a fascinating piece of history, but for the Brontës it was also a part of their present.

At the time of the battle, the Brontë family had four members: Patrick and Maria and their two daughters Maria and Elizabeth. They were followed by Charlotte, Branwell, Emily, and Anne. Throughout their lives the children would read stories about the heroism displayed on that Belgian battlefield, hanging on every word carried by jingoistic papers they read such as ‘John Bull’.

Their father, Patrick, was a great admirer of his fellow Irishman Arthur Wellesley, the Duke of Wellington, and would often talk of his exploits and his genius when it came to war. The children were enthralled by these tales, and soon began to worship Wellington themselves. On 5th June 1826 Patrick, realising how keen his children were on Waterloo and military matters in general, brought a set of wooden soldiers for them. A few years later Charlotte recounted the story:

“Papa bought Branwell some wooden soldiers at Leeds. When Papa came home it was night, and we were in bed, so next morning Branwell came to our door with a box of soldiers. Emily and I jumped out of bed, and I snatched up one and exclaimed: ‘This is the Duke of Wellington! This shall be the Duke!’ when I had said this Emily likewise took one up and said it should be hers; when Anne came down, she said one should be hers. Mine was the prettiest of the whole, and the tallest, and the most perfect in every part. Emily’s was a grave-looking fellow, and we called him ‘Gravey’. Anne’s was a queer little thing, much like herself, and we called him ‘Waiting-boy’. Branwell chose his, and called him Buonaparte.”

The Brontë children could now re-enact the Battle of Waterloo in their own home, and did so at every opportunity. It wasn’t long, however, until they were dreaming up new adventures for their soldiers, the ‘Young Men’ as they were now called. This invented land was called The Glass Town Confederacy, which later led to Angria and Gondal. From this early play they developed what they called a ‘scribblomania’, writing stories and poems about the exploits of their soldiers. This passion for writing would never leave them, and of course resulted in the books the world so loves today.

The love that Anne, Charlotte, Emily and Branwell had for military stories may have resulted from stories told by their Aunt Branwell. Penzance, where she and their mother Maria grew up, was an important naval centre at the time – and indeed it was Penzance that first heard the news that Admiral Horatio Nelson had died at the Battle of Trafalgar in 1805. The returning warship HMS Pickle passed the news to a fishing boat who headed straight back to port, where the news was then broadcast from the balcony of the Union Hotel on Chapel Street – an event that is re-enacted annually. Nelson, of course, was responsible for the name of the famous writing family of Haworth. In recognition of his exploits he was given Bronte castle in Sicily. This fact was uppermost in the mind of Patrick Prunty, who adored Nelson, when he chose to anglicise his name upon attending Cambridge University.

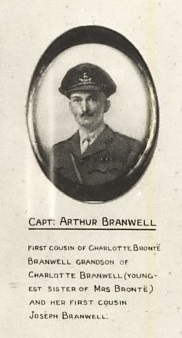

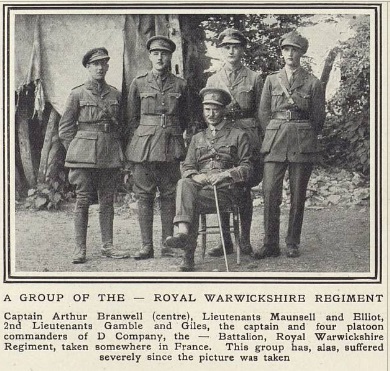

Of course, at the moment our minds are particularly focused on the terrible conflict that was World War 1 – and Brontë relatives were represented here too in the shape of Captain Arthur Milton Cooper Branwell. During the war he was a Captain in the Royal Warwickshire Regiment’s 4th Brigade. The following picture appeared in The Tatler of 23rd August 1916 when fighting on the Western Front was approaching its fiercest. As the senior officer, the grand looking Captain Branwell is seated at the centre, but as noted by the caption many of the officers around him were by then dead.

Captain Branwell himself escaped the horrors of the trenches however, as the 4th Brigade was the Royal Warwickshire’s Extra Reserve, and in fact it never left England during the duration of the war. He was heavily involved in training new recruits, and was ready and willing to fight in France if called upon, despite being then in his mid fifties.

He was a veteran of the army who had been recalled at the start of World War 1, and had fought in the Boer War among other conflicts – it was here probably that he met the soldier Edgar Wallace. Wallace turned his hand to writing, and became so prolific that his agent famously claimed that one in four books published in England were by him. He had over 170 novels and 957 short stories published, and was also the author of 18 stage plays and countless film scripts – he was working on an adaptation of his own King Kong when he died. Wallace was particularly popular for his army stories about a private called Smithy – and one copy of Smithy preserved today includes a two page dedication to his former comrade in arms Arthur Branwell.

We may think that a soldier in ‘The Great War’ must be a distant relative of the Brontës, but not so. Born in 1862, he was in fact a first cousin once removed of the Brontë sisters – his father Thomas Brontë Branwell was the Brontë cousin who visited Charlotte and Patrick in Haworth in 1851.

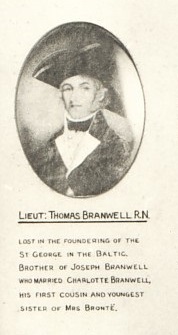

Another Brontë relative, via the Branwell family, served in the navy, as did many in Penzance, but paid the ultimate price.

Lieutenant Thomas Branwell was a cousin of Maria and Elizabeth Branwell, and his closeness to them is shown by the fact that he had his miniature portrait painted at the same time as Maria and Elizabeth, in all his navy finery. He must have been the pride of the Branwells but terrible news came at the end of 1811, as reported by the Navy Chronicle of January 1812:

‘The St. George, Defence, and Cressey, kept the North Sea five days, in a dreadful gale from the W.N.W. west and south; but, at length, had to combat with a terrible tempest from the N.W. until they were lost. The following is a list of the principal officers who were on board the St. George and Defence when those vessels were wrecked – In the St. George Admiral Reynolds, Captain Guion, Lieutenants Napier, Place, Thompson, Brannel, Dance, Tristram, Riches, and Rogers.’

Brannel was of course Thomas Branwell, who died at sea onboard HMS George off the coast of Denmark. It was a naval tragedy on a horrendous scale, with 731 of the 738 man crew losing their lives and many hundreds more dying on board the Defence. It is rumoured that he and his cousin Elizabeth were in love, and if so this may explain why Aunt Branwell remained resolutely single for the rest of her life.

Lieutenant Branwell died during the Napoleonic Wars, Captain Branwell served with honour during the first World War. On this weekend we should remember them, and other brave souls who were ready to give their today for our tomorrow.