They say that money makes the world go around, although others would contend that it’s love that makes everything tick – both these things continue to elude me, but even I am fascinated by the love lives of the Brontës: did Charlotte’s loves infuse her writings, did Anne really fall for her father’s assistant, and did Emily love anyone at all? It’s time to brighten up this grey January morning by looking at the Brontës in love.

As a young girl Charlotte Brontë developed a crush on the Duke of Wellington. He was to her what Harry Styles might be to a girl today. Of course she didn’t have a poster on her wall, so instead she had to make do with reading of his exploits in books and the newspapers of the day. This also helped to fuel her amazing creativity; as a young child she, in cahoots with Branwell, Emily and Anne, would act out and write intricate stories set in a land of their making called Angria, and in these early days Wellesley, the Duke of Wellington, was always sure to be the hero. Do you remember what Charlotte said when her father brought them a set of toy soldiers? She snatched one up and shouted, ‘This is the Duke of Wellington! This shall be the Duke!’

In real life it was hard for anyone to live up to the example of the Duke, and Charlotte wasn’t a woman who would put up with second best. She turned down at least three marriage proposals that we know of, despite being a less than prepossessing woman herself – she was around four and a half feet tall with bad eyesight and missing teeth. The first proposal she turned down was from Henry Nussey, brother of her best friend Ellen, saying that she could never marry someone she didn’t find attractive. He later married a woman called Emily Prescott and become a Church of England vicar in Hathersage, Derbyshire.

Hathersage today has a particular claim to fame – it’s recreated as Morton in Jane Eyre. Charlotte occasionally stayed with Ellen there, and she would have met the richest local family – the Eyre family of North Lees Hall. What’s not as well known is that Henry Nussey didn’t stay in Hathersage long. Within two years he gave up his life as a clergyman, suffering from some form of mental illness. By 1860 he was incarcerated in Arden House Lunatic Asylum, where he tragically hanged himself.

Perhaps Charlotte’s greatest love of all was for a man named Constantin Heger. Aged 25 she travelled to Belgium in company with her sister Emily, and she remained there for two years, with a return to Haworth in the middle after the death of her aunt. She had gone ostensibly to learn French and German, so that the three sisters could set up their own school on their return; but the truth was that she wanted to see something of the world outside Yorkshire, and her other great friend Mary Taylor was already staying in Brussels.

Monsieur Heger was a professor at the school attended by Charlotte and Emily. He was a proud, strong man, somewhat aloof and exacting, a bit cold and mysterious, a man who dominated all around him. Sound familiar? Charlotte had met her Mr Rochester, she loved being ordered around by him, while she submissively followed his orders. There were two problems – one, he was married to the school’s headmistress, and two he didn’t share her strong feelings.

After returning permanently to Haworth, Charlotte wrote M. Heger a string of yearning love letters. Her passion, as so often with Charlotte, was out of control. One such epistle ended ‘I cannot – I will not resign myself to the total loss of my master’s friendship – I would rather undergo the greatest bodily pains than have my heart lacerated by searing regrets.’

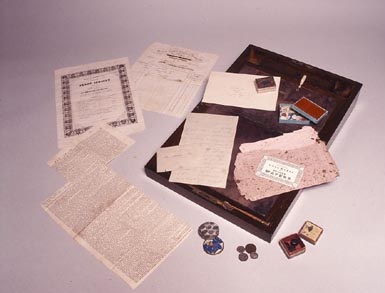

He never replied to any of her letters, and indeed cut them up. For some reason however his wife stitched them back together again, which is why we now have them in the British library. There must have been a frosty atmosphere around the Heger dining table on the days that yet another letter arrived from England.

It seems that Constantin soon forgot Charlotte, if indeed he’d ever thought of her, but she would never forget him. He was not only the inspiration for Rochester but also for her Belgium based novels The Professor and Villette.

There was another man that Charlotte had esteemed, her father’s good looking assistant curate William Weightman. To be fair he seemed to charm all the women he met, and it was he who in 1840 had sent the sisters their first ever Valentine’s day card. To hide the fact the cards had come from him he walked from Haworth to Bradford to post them, sending one for each with a personalised verse inside – one for Charlotte, Emily and Anne and another for Ellen Nussey who was on one of her visits to the Parsonage at the time.

The sisters, then aged between 20 and 24, must have been delirious with excitement, although they soon worked out who had sent them. It was an act of kindness from Weightman that was typical of the man, but Charlotte once more took it all too much to heart. She spent weeks drawing his portrait, and being roundly teased for it, and lauding him in her letters, but that was soon to change dramatically.

By February 1841 when Weightman again sends the girls a set of Valentine’s cards, it gets a very different reception from Charlotte. She writes to Ellen:

“I knew better how to treat it than I did those we received a year ago. I am up to the dodges and artifices of his Lordship’s character, he knows I know him… for all the tricks, wiles and insincerities of love the gentleman has not his match for 20 miles round.”

What has caused this change? It seems to me that Charlotte was jealous that Weightman had overlooked her love for him, and instead turned his eye on to somebody else – someone who to Charlotte would represent the greatest betrayal of them all. The clues are there.

In another letter of this time she writes that Weightman sits opposite Anne at church, sighing softly to gain her attention. ‘And Anne is so quiet, her looks so downcast – they are a picture.’

Could this be the truth – that Weightman had passed over Charlotte for her youngest sister? Was he the one and only love of Anne Brontë’s all too brief life, a love that would only find fruition in Anne’s writings after Weightman’s untimely death.

Despite Charlotte’s portrayal of him, Weightman was a very kind hearted and sincere man, which is why after his death the Haworth parishioners dipped into their own pockets to have a large tribute to him erected in their church. He often visited sick parishioners, taking them food and drink and reading to them, but in a village as disease ridden as Haworth that was like playing Russian roulette. In August 1842 he contracted cholera from a parishioner he was visiting, and died 2 weeks later aged just 28.

Anne was away on governess duties near York at the time, but her grieving would last for the rest of her life. Had they had an agreement with each other in real life, did they harbour hopes that they could one day be married? It certainly wouldn’t be unusual for a young curate to seek a wife from the daughters of another clergyman, and Anne was described by contemporaries as the prettiest of the Brontë sisters, as well as being the most pious. We’ll never know whether they did acknowledge their love for each other, although I hope so – it’s the old romantic in me.

What we can say for sure is that after Weightman’s death, Anne created a series of poems mourning the death of a loved one. Poems with opening lines such as ‘I will not mourn thee lovely one, though thou art torn away’ and later ‘Severed and gone so many years! And art thou still so dear to me.’ She also chose to portray Weightman as Reverend Weston in her first novel, the wonderful ‘Agnes Grey‘ – to me the most underrated book ever written. She shows Weston visiting the sick, taking them food and fuel, rescuing their pets, all things she had witnessed Weightman do in real life. At the end of the novel, spoiler alert, Agnes, who is very closely modelled on Anne herself, marries Weston. In print at least Anne is giving herself the happy ending she was denied in real life – that’s my opinion, but others may disagree with my conclusion. That’s one of the great things about the Brontës, we can all create our own theories, each as valid as the other.

So we’ve seen Anne’s possible love, but what about Emily? Could the creator of Cathy and Heathcliff really have never had a love of her own, not even an unrequited love of her own? It’s something we’ll never know, unfortunately – certainly there is no record in diaries or letters of Emily forming an attachment to anyone except her mastiff Keeper and her sister Anne, with whom she was so close that they were talked of as being like twins. It would be nice to think that she did have a love for someone, but it seems very unlikely. One early twentieth century biographer, Virginia Moore, discerned a faint name in pencil on an Emily Brontë manuscript, and announced excitedly to the world that she had discovered Emily’s secret love – Louis Parensell! Unfortunately a closer examination of the manuscript in question showed that the pencil marks actually read ‘Love’s Farewell’, an alternative title to the poem below it.

We’ll finish on a happier note, and return to Charlotte again. She had a suitor who had been taking an interest in her for many years, and once again it was an assistant curate to her father – Reverend Arthur Bell Nicholls.

After Branwell, Emily and Anne died within nine months of each other in 1848 and 1849, Charlotte felt bereft and alone, frequently suffering from attacks of depression and writing that she was ‘driven often to wish I could taste one draught of oblivion and forget much that, while mind remains, I shall never forget.’

In these darkest moments, Arthur acted as a friend to her, and he even took up the duty of walking the dogs Keeper and Flossy that had belonged to Emily and Anne. Charlotte was seemingly unaware of his real feelings towards her however, so it came as a big shock to all concerned when in December 1852 he asked her father for her hand in marriage. Patrick was furious; this was a man who had been a great help in his church, and was a fellow Irishman, yet Charlotte was by now a successful writer, and he thought his daughter could do better for herself. Patrick was also by then an old man, and worried how he could cope if Charlotte wasn’t there to look after him. Charlotte was just as angry, professing that she didn’t and couldn’t love him.

The spurned Arthur suddenly found himself persona non grata in the Parsonage, and announced he was leaving Haworth to become a missionary in Australia. Charlotte recorded what happened at the last service he officiated at. He mounted the steps to the pulpit, and then stood there shaking, unable to speak. Eventually some of the congregation helped him down and led him outside, with many of the parishioners in tears. Charlotte later found him by a wall, ‘sobbing as no man has ever sobbed.’

Arthur didn’t go to Australia, he went somewhere less exotic – Kirk Smeaton near Selby. From there he continued to write to Charlotte, and his persistence won her round, as did his promise that they would continue to live at Haworth and look after her father if they wed.

On 29th June 1854, they married in Haworth. Patrick said that he was too ill to attend, so Charlotte’s old headmistress Miss Wooler had to give her away instead. Even at this point Charlotte professed little liking for her new husband, but this rapidly changed. To her great surprise Charlotte found that she loved married life and she loved Arthur. Now at last, after 38 years of loss and sadness, Charlotte Brontë was truly happy. Let us end on that uplifting note, after all what the world needs now is love, sweet love – even if only taken vicariously through the great novels of the Brontë sisters.