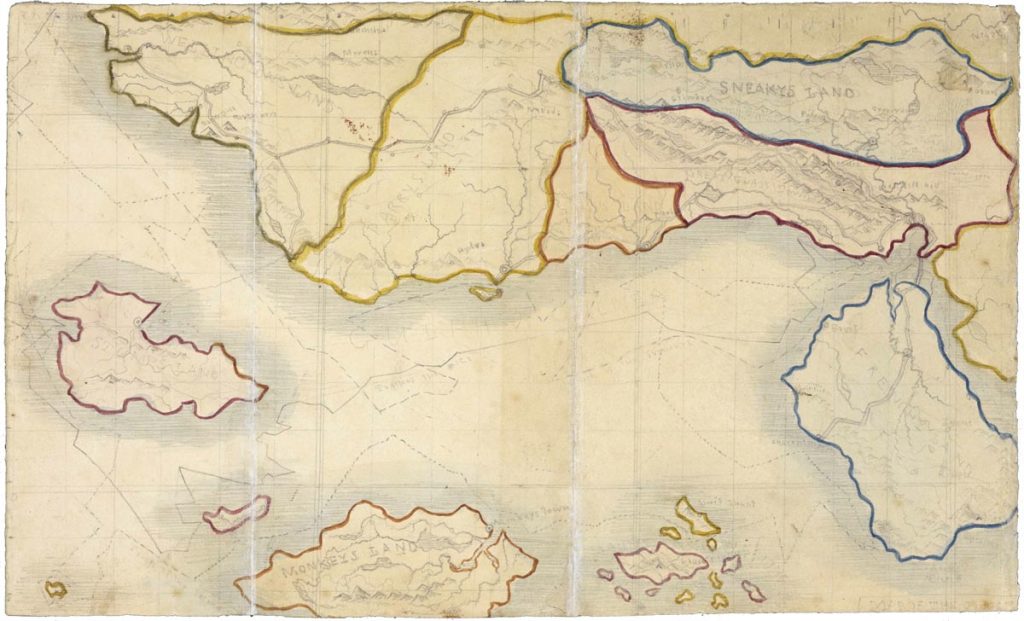

The adult writing of the Brontë sisters that we so love today have their roots in the youthful writings of four siblings that centred upon two imaginary universes – Angria and Gondal.

Angria was the first land to be created and it flowed from childhood games and tales that had developed from a set of twelve soldiers bought for Branwell in 1826. These early Angrian adventures form the bulk of material into the incredible little books that can be seen at the Brontë Parsonage Museum today. Belying the tender years of their creators, the Angrian adventures are complex, full of spies, passion, double dealings and bloodshed, but they also contain a welcome streak of humour, with mock adverts in the style of those they found in their father’s literary magazines.

The Angrian writing was done exclusively by the older siblings Charlotte and Branwell, but Emily and Anne Brontë were encouraged to make verbal suggestions from the sidelines, and their contributions appear in the tales under the guises of the Genius Emmii and the Genius Annii.

Being a genie and listening to their adventures in a far off land was great fun for the youngest sisters, particularly as Tales From The Arabian Knights was one of their favourite books, but soon they wanted to take a more active role. Their opportunity came in 1831, when Charlotte left Haworth to become a pupil at Roe Head School in Mirfield. By now Anne and Emily were 11 and 13 respectively, and it wasn’t long before they decided to create a world of their own – the world of Gondal. This was an island kingdom of their own imagining that was frequently at war with the neighbouring state of Gaaldine.

Gondal helped to cement the twin like bond between Anne and Emily. They would take long walks on the moors together discussing the next development in the Gondal saga. They would spend hours in the Parsonage whispering plots into each others ears. Gondal was their land – and it was a land full of even more intrigue and passion than Angria had been. One of the major recurring characters in Gondal is Alexandria Zenobia, and the choice of name in this instance is very telling for they had encountered a real life Zenobia in the periodicals they loved to read – and even more excitingly, the tales of this flesh and blood Zenobia were related by a man who was known by their Aunt Branwell – and who was related to her and the mother who had tragically died during their infancy.

John Carne of Penzance was a second cousin of Elizabeth and Maria Branwell, whose mother’s maiden name had been Anne Carne. He was a well travelled man who write books about his journeys across what were then, to the people of England, largely unknown countries and continents. John’s 1826 book ‘Letters from the East’ was a great success and excerpts were printed in a number of publications including The Quarterly Review. It contains lurid descriptions and fantastical tales that had the young Brontë’s gasping with excitement, including his description of the British explorer and archaeologist Lady Hester Stanhope, niece of former Prime Minister William Pitt the Younger. Frequently crossing hostile territories she was feted by locals and hailed as ‘Zenobia, Queen of Syria’ in memory of an earlier Queen who is pictured at the top of this post:

‘Her restless and romantic mind dwelt with pleasure on the idea of a power to be established in the East, of which she was to be the mistress: – a large fleet was to come from afar to aid this conquest, and her sceptre was to wave with equal glory to that of Zenobia who defended Palmyra.’

Did Emily or Anne see themselves as a Lady Hester Stanhope as they gazed upon their own territory, the moors of Haworth? Did they dream of becoming a writer like their relative John Carne? Their names have deservedly survived much longer of course, and the name Zenobia itself is now most famous for its association with a poem Anne Brontë wrote when she was just 17. Entitled ‘Alexander and Zenobia’, I leave you with an extract from it now:

‘Fair was the evening and brightly the sun,

Was shining on desert and grove,

Sweet were the breezes and balmy the flowers,

And cloudless the heavens above.

It was Arabia’s distant land,

And peaceful was the hour;

Two youthful figures lay reclined,

Deep in a shady bower.

One was a boy of just fourteen,

Bold beautiful and bright;

Soft raven curls hung clustering round,

A brow of marble white.

The fair brow and ruddy cheek,

Spoke of less burning skies;

Words cannot paint the look that beamed,

In his dark lustrous eyes.

The other was a slender girl,

Blooming and young and fair,

The snowy neck was shaded with,

The long bright sunny hair,

And those deep eyes of watery blue,

So sweetly sad they seem’d,

And every feature in her face,

With pensive sorrow teem’d.

The youth beheld her saddened air,

And smiling cheerfully,

He said “How pleasant is the land,

Of sunny Araby!

Zenobia, I never saw,

A lovelier eye than this;

I never felt my spirit raised with more unbroken bliss!..

So pleasant are the scents that rise,

From flowers of loveliest hue,

And more than all – Zenobia,

I am alone with you!’