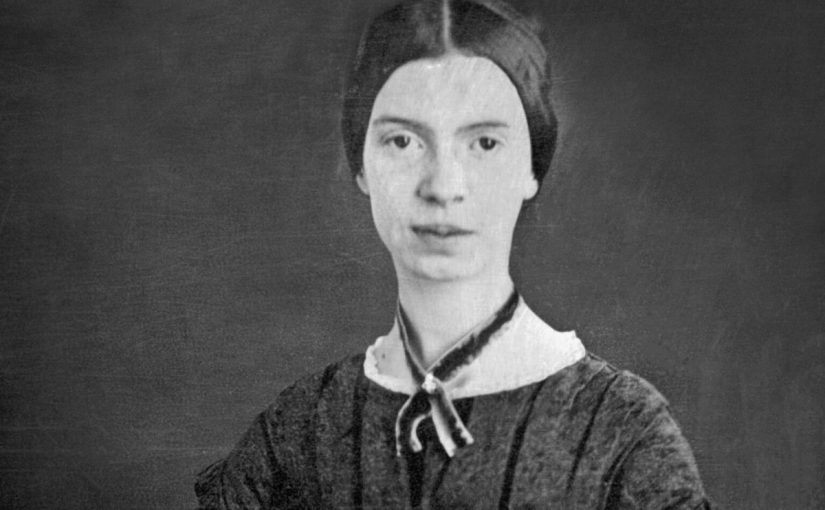

Emily was a brilliant and prolific poet, a genius born in the early nineteenth century. Her writing dazzled with invention and soaring thoughts, but it also often dealt with themes of death. Emily never had a lover and as she grew older she became increasingly reclusive, often refusing to meet or talk to guests, and spending most of her later years confined to her bedroom with only pen and paper for company. She kept her poems to herself, and it was only after the accidental discovery of them by her sister that they came to the world’s attention. You may think I’m talking about Emily Brontë, but in fact this is Emily Dickinson – in my opinion America’s greatest ever poet, and a woman who died 132 years ago this week, aged 55.

Emily Elizabeth Dickinson was born in Amherst, Massachusetts in December 1830 into a comfortable, if not overly wealthy, family and had one brother William Austin (always known by his middle name) and a sister Lavinia. At age nine she was sent to the Amherst Academy, where she stayed for seven years, and she excelled at her learning. She particularly loved to play the piano, which she was proficient at from an early age. Even at this age, however, Emily knew that she did not fit in with the regimented life others followed:

‘They shut me up in Prose –

As when a little Girl

They put me in the Closet –

Because they liked me “still” –

Still! Could themself have peeped –

And seen my Brain – go round –

They might as wise have lodged a Bird

For Treason – in the Pound –’

In 1844 a tragedy struck that changed Emily’s life for ever. Her cousin and best friend Sophia Holland contracted typhoid and died. From that moment melancholia settled upon Emily Dickinson, and she was often consumed by thoughts of death, illness and dying; thoughts that inevitably found their way onto the page.

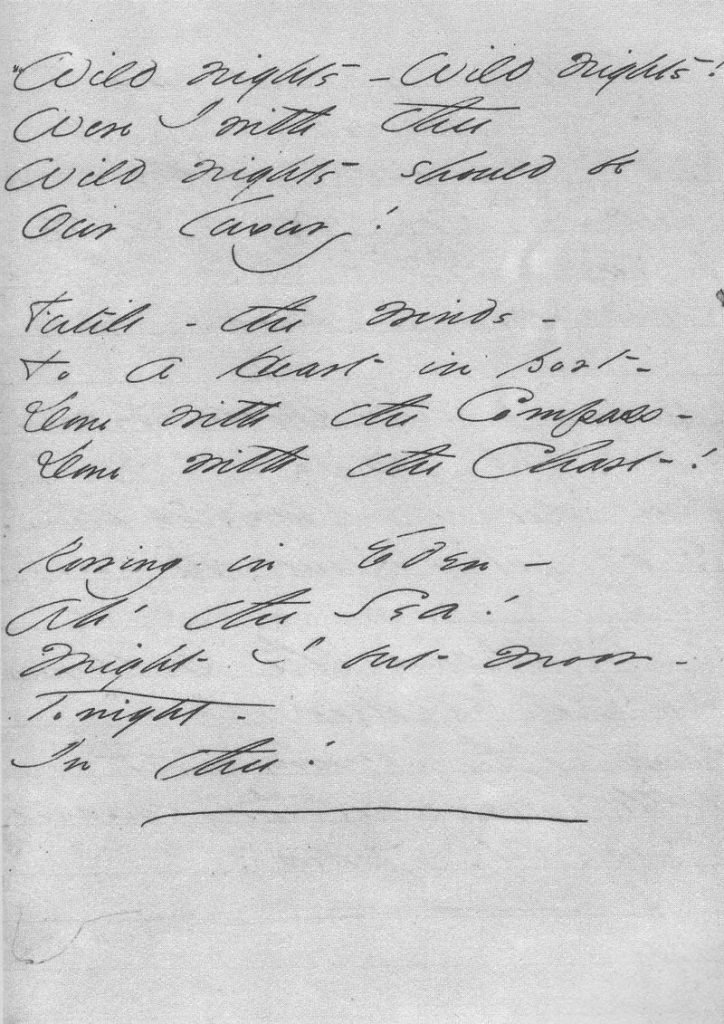

By 1858 Emily had become a recluse, and in the privacy of her own room she began to edit and collect the poems she had been writing over the years into four notebooks. They contained over 800 poems, many of them as brilliant as anything written that century and stylistically way ahead of their time as Emily often cut up her poetry with dashes or a strange use of capitalisation. These books were discovered by Lavinia after Emily Dickinson’s death, and it was only then that it was realised what she had truly been. Emily never wanted fame or even recognition, as her poem ‘Fame Is A Fickle Food’ shows:

‘Fame is a fickle food

Upon a shifting plate

Whose table once a

Guest but not

The second time is set

Whose crumbs the crows inspect

And with ironic caw

Flap past it to the

Farmer’s corn

Men eat of it and die.’

Emily’s faith was unique to herself, she attended church for but a few years, but she believed in a universal power and in the immortal, unbreakable soul. By 1867 her isolation was complete, so that she would only talk to people on the opposite side of her door. In these last 20 years she continued to write incredible poems that became darker and darker, like ‘Because I Could Not Stop For Death’:

‘Because I could not stop for Death –

He kindly stopped for me –

The Carriage held but just Ourselves –

And Immortality.

We slowly drove – He knew no haste

And I had put away

My labor and my leisure too,

For His Civility –

We passed the School, where Children strove

At Recess – in the Ring –

We passed the Fields of Gazing Grain –

We passed the Setting Sun –

Or rather – He passed Us –

The Dews drew quivering and Chill –

For only Gossamer, my Gown –

My Tippet – only Tulle –

We paused before a House that seemed

A Swelling of the Ground –

The Roof was scarcely visible –

The Cornice – in the Ground –

Since then – ’tis Centuries – and yet

Feels shorter than the Day

I first surmised the Horses’ Heads

Were toward Eternity –’

On May 15th 1886, Emily Dickinson died suddenly with her brother by her side. She had imagined her own funeral many times,and featured it in her verse:

‘I felt a Funeral, in my Brain,

And Mourners to and fro

Kept treading – treading – till it seemed

That Sense was breaking through –

And when they all were seated,

A Service, like a Drum –

Kept beating – beating – till I thought

My mind was going numb –

And then I heard them lift a Box

And creak across my Soul

With those same Boots of Lead, again,

Then Space – began to toll,

As all the Heavens were a Bell,

And Being, but an Ear,

And I, and Silence, some strange Race,

Wrecked, solitary, here –

And then a Plank in Reason, broke,

And I dropped down, and down –

And hit a World, at every plunge,

And Finished knowing – then -‘

Emily Dickinson found immense fame after her death, as Emily Brontë did, and the poems of both Emilys have astonished the world ever since. There are huge, some would say strange, similarities between the two women, but did Emily Dickinson know of the Brontës? She certainly knew, and loved, their work. In 1849 we know that Emily Dickinson read the first American edition of ‘Jane Eyre‘. It made such an impact on her that she later named her new puppy ‘Carlo’, after St. John’s dog in Charlotte Brontë’s great novel. At Emily Dickinson’s funeral a solitary poem was read; it had been specifically requested by her: it was ‘No Coward Soul Is Mine’ by Emily Brontë!

Yes, a deep kinship in female pespective, male obscured talent, wordly isolation, and time transcendent vision.

I want to read more about Emily Bronte and have heard more about Emily Dickinson so I googled both names together and found this article. I look forward to learning more about Emily and the Brontes. I want to share this link since this article reiterates what has been challenged as a lie of omission about Emily Dickenson’s life that has since come to light: https://www.bustle.com/p/how-accurate-is-wild-nights-with-emily-the-biopic-explores-a-queer-romance-that-was-censored-out-of-history-17006045