Firstly, my apologies for not uploading a post last Sunday! I was in Haworth enjoying a weekend that was beautiful in every way, so whilst I may not have been able to commit the Brontës to my blog as I like to do they felt close to me in every other way. It was my first chance to see the new Emily Brontë exhibition, ‘Making Thunder Roar’, and one part that I did like was a video installation featuring actress Chloe Pirie reading Emily’s poetry to a background of hawks and moorland scenery.

The idyllic Haworth days are now stored to memory to bring a smile and peaceful thoughts whenever I need them. Normal service is now resumed, and in today’s post we’re going to take a Brontë inspired look at Father’s Day. We’ve examined the role of Reverend Patrick Brontë a number of times recently, but it’s worth saying again that in my opinion his contribution to the Brontë story is huge. He was a poet and inspiration, a man who gave all he had to help his children and his community, one who encouraged his daughters in their creative endeavours and allowed them free access to whatever books they liked – something which would have been anathema to many other early 19th century parents.

Yes, we should certainly say ‘Happy Father’s Day, Patrick Brontë’ but today we are looking at two other dads – the grandfathers of the Brontë siblings. Whilst Maria, Elizabeth, Charlotte, Branwell, Emily and Anne never met either of their grandparents they would have heard stories of them, and very inspirational stories they would have been too.

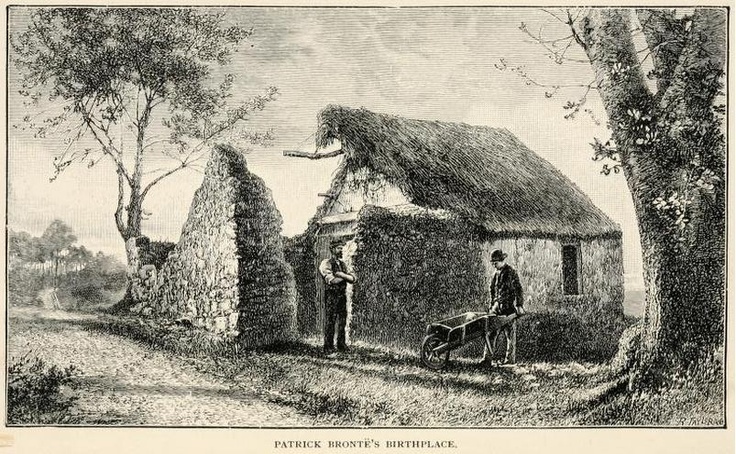

Hugh Prunty (or Brunty) was Patrick’s father. Hugh was born in Ireland into a Protestant family in the mid eighteenth century, and Patrick himself gave Elizabeth Gaskell this remembrance of his father:

‘He was left an orphan at an early age. It was said that he was of ancient family… He came to the north of Ireland and made an early but suitable marriage. His pecuniary means were small – but renting a few acres of land, he and my mother by dint of application and industry managed to bring up a family of ten children in a respectable manner.’

If Hugh was left an orphan at an early age, who raised him? It’s here that the story gets particularly interesting as a 19th century biography relates a tale of a man called Welsh Brunty raising the child as his own. Welsh himself was rather a cuckoo in the nest, and the story of how he came to the Brunty family is told thus:

‘On one of his [Patrick’s great grandfather, a farmer and merchant from County Louth] return journeys from Liverpool a strange child was found in a bundle in the hold of the vessel. It was very young, very black, very dirty, and almost without clothing of any kind. No one on board knew whence it had come, and no one seemed to care what became of it. There was no doctor in the ship, and no woman except Mrs. Brontë, who had accompanied her husband to Liverpool. The child was thrown on the deck. Some one said, “Toss it overboard”; but no one would touch it, and its cries were distressing. From sheer pity Mrs. Brontë was obliged to succour the abandoned infant… When the little foundling was carried up out of the hold of the vessel, it was supposed to be a Welsh child on account of its colour. It might doubtless have laid claim to a more Oriental descent, but when it became a member of the Brontë family they called it “Welsh”.’

Later in this tale the adult Welsh takes the young Hugh from his family, and in this we can see a clear precursor of the mysterious foundling Heathcliff and his treatment of his adoptive family.

What we know for sure about Hugh is that he fell in love with a Catholic girl named Alice McClory from County Down – this crossing of religious lines was dangerous, yet Patrick and Alice eloped together and were married in Magherally church. They then settled down to married life in Drumballyroney, where in 1777 they had the first of twelve children: christened after the patron saint of his birthday, he became of course Patrick Brontë.

We have one more memory of Brontë grandfather Hugh, and it comes from his daughter, and Patrick’s sister, Alice. Reminiscing in 1891, at the grand old age of 95, she recalled:

‘My father came originally from Drogheda. He was not very tall but purty stout; he was sandy-haired and my mother fair-haired. He was very fond to his children and worked to the last for them.’

Let us now turn to the other Brontë grandfather, their maternal grandpa Thomas Branwell of Penzance. We all know how Patrick changed his name from Prunty or Brunty to Brontë, well, the same process occurred in Cornwall too, for Thomas Branwell had been born Thomas Bramwell and a couple of generations earlier they were the Bramble family.

The change of name may reflect Thomas’ changing status, for he became an extremely successful business man and a leading figure in Penzance politics. His will, dated March 26th 1808, lists a magnificent array of property and wealth, including houses across Penzance, the largest mansion in the area Tremenheere House, shops, a quayside warehouse, a pub called The Golden Lion and his own brewery (these last two perhaps rather strange acquisitions for a committed Methodist and teetotaller).

Thomas married into another wealthy Penzance family, when he wed Anne Carne, for her family founded Penzance’s first bank ‘Batten, Carne & Carne’ in 1797. It seems likely that Anne Brontë knew of the wealth and status of her grandparents when she wrote at the beginning of ‘Agnes Grey’:

‘My mother, who married him against the wishes of her friends, was a squire’s daughter, and a woman of spirit. In vain it was represented to her, that if she became the poor parson’s wife, she must relinquish her carriage and her lady’s-maid, and all the luxuries and elegancies of affluence.’

Thomas Branwell was never a squire, he was new money after all rather than landed gentry, but his son Benjamin did rise to become Mayor of Penzance in 1809.

Thomas and Anne, like Hugh and Alice, had twelve children, although again not all survived childhood. Benjamin Branwell became mayor, but it is two more of his children that are remembered on a plaque on their former residence in Chapel Street, Penzance; Elizabeth, born in 1776, and Maria, born 1783. The plaque proudly proclaims:

‘This was the home of Maria and Elizabeth Branwell, the mother and aunt of Charlotte, Emily, Anne and Branwell Brontë.’

Thomas and Hugh must have been good fathers, for they certainly produced two wonderful children in Patrick and Maria, who in turn were good and loving parents. To Patrick, Hugh, Thomas and fathers across the world I say ‘Happy Father’s Day’ (and God bless the women who do all the work behind the scenes as well!)

Could you please provide the reference for the story of the baby Welsh?

Thanks

Hi Clare, it’s from an 1893 book called ‘The Brontes In Ireland’ by William Wright – it’s available to read for free online.