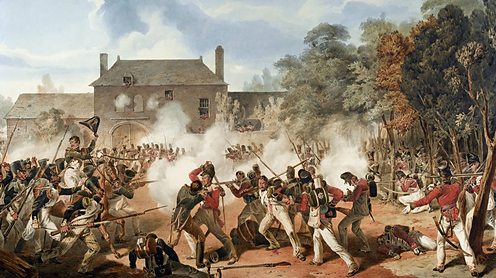

Visitors to Haworth at certain times of the year may be lucky enough to see men and women in nineteenth century clothing, but in a certain corner of Belgium this week there was an opportunity to see nineteenth century attire of a very different kind. That’s because this week marked the 203rd anniversary of the Battle of Waterloo. June 18th 1815 saw Arthur Wellesley, more famously known today as the Duke of Wellington, and his Prussian allies under the leadership of General Gebhard Leberecht von Blucher, inflicted a decisive defeat on the increasingly tyrannical Napoleon Bonaparte. It is a fascinating piece of history, but for the Brontës it was very much part of their present.

At the time of the battle, the Brontë family had four members: Patrick and Maria and their two daughters Maria and Elizabeth. Charlotte was born less than a year after the battle, followed by Branwell, Emily, and Anne. Throughout their lives the children would read stories about the heroism displayed on that Belgian battlefield, hanging on every word carried by jingoistic papers they read such as ‘John Bull’.

Their father, Patrick, was a great admirer of his fellow Irishman Arthur Wellesley, the Iron Duke, and would often talk of his exploits and his genius when it came to war. The children were enthralled by these tales, and soon began to worship Wellington themselves. On 5th June 1826 an event occurred which would change the course of literary history forever.

Patrick, realising how keen his four surviving children (Maria and Elizabeth by this time having succumbed tragically to tuberculosis contracted at Cowan Bridge’s Clergy Daughters School) were on Waterloo and the associated tales of heroism, brought a set of wooden soldiers for them. A few years later Charlotte recounted the story:

“Papa bought Branwell some wooden soldiers at Leeds. When Papa came home it was night, and we were in bed, so next morning Branwell came to our door with a box of soldiers. Emily and I jumped out of bed, and I snatched up one and exclaimed: ‘This is the Duke of Wellington! This shall be the Duke!’ when I had said this Emily likewise took one up and said it should be hers; when Anne came down, she said one should be hers. Mine was the prettiest of the whole, and the tallest, and the most perfect in every part. Emily’s was a grave-looking fellow, and we called him ‘Gravey’. Anne’s was a queer little thing, much like herself, and we called him ‘Waiting-boy’. Branwell chose his, and called him Buonaparte.”

Branwell also remembered this day, but his recollection of how the soldiers were distributed is slightly different to that of his sister:

“I carried them to Emily, Charlotte and Anne. They each took up a soldier, gave them names, which I consented to, and I gave Charlotte Twemy, to Emily Pare, to Anne Trot to take care of them, although they were to be mine and I to have the disposal of them as I would.”

It is no surprise that Charlotte named her soldier Wellington, she worshipped him in the same way that a young girl today would worship the latest boy band. In Branwell’s choice of Napoleon, we also get an early glimpse of the rebellious streak that was later to become so painfully apparent.

The Brontë children could now re-enact the Battle of Waterloo in their own home, and did so at every opportunity. It wasn’t long, however, until they were dreaming up new adventures for their soldiers, the ‘Young Men’ as they were now called. This invented land was called The Glass Town Confederacy, which later led to Angria and Gondal. From this early play they developed what they called a ‘scribblomania’, writing stories and poems about the exploits of their soldiers. This passion for writing would never leave them, and of course resulted in the books the world so loves today.

There is one particularly fascinating object belonging to the Brontë Parsonage collection – a fragment of Napoleon’s coffin! It was presented to Charlotte by Constantin Heger, her Belgian tutor and the unrequited target of her affections.

The voyage of Charlotte and Emily to Brussels in 1842, to study at the Pensionnat Heger with a view to later setting up their own school with Anne in Haworth, brought them close to the Waterloo battlefield, and indeed Brussels at this time was home to many British ex-servicemen and their families who had fought in the battle. It is believed that Patrick, who travelled to Brussels with his two daughters, took the opportunity of visiting Waterloo before returning to England. Years later, Charlotte finally met her hero. On 12th June 1850 she, by then a successful author but the last surviving of the six Brontë siblings, wrote to Ellen Nussey to say that she had seen the Duke of Wellington, by then in his eighties, in London’s Chapel Royal. Charlotte’s childhood adoration resurfaced, her mind went back to the soldier she had snatched up, and she wrote that he was ‘a real grand old man’.

If the Iron Duke had not defeated Napoleon on that June day more than two hundred years ago, the course of history could be very different. Wellington may not have been worshipped in that Yorkshire parsonage, the soldiers may never have been bought, and we may never have had those seven magnificent Brontë novels. That’s why lovers of Anne Brontë and her sisters should this weekend raise a glass and toast the soldiers of Waterloo, and their courage to face head on tyranny and evil, to face it and defeat it.