This weekend witnessed a special festival in Whitby to mark the 250th anniversary of a voyage of discovery by one of North Yorkshire’s most famous sons, Captain James Cook. The voyage was aboard his ship Endeavour, and left England in 1768. During two long voyages on HMS Endeavour he became the first European to map much of the South Sea and to discover New Zealand and Australia.

Cook was doubtless an inspiration to his fellow Yorkshire natives the Brontës as it was their love of tales of exploration that had a huge influence on their childhood tales of Angria and Gondal. These tales, in tiny, intricate books led of course to the adult novels of the Brontë sisters that we love so much.

The sea features heavily in Anne Brontë’s work, mainly in the form of the Scarborough coastline that she adored and which filled her soul in the same way the Haworth moors did for Emily. It is in Charlotte’s work, however, that we get glimpses of the perilous voyages that explorers like Cook embarked upon.

Jane Eyre’s uncle dies in far off Madeira and leaves her a fortune that transforms her life, whilst Rochester has brought more than gold back from the Caribbean. In ‘Villette’, the heroine Lucy Snowe’s love Paul Emmanuel is hinted to have died in a shipwreck, although in a brilliant plot device the reader is left to determine for themselves whether this was his end or not.

James Cook moved to Whitby in his late teens, and embarked upon a naval career that would see him achieve legendary status. Whitby itself is around 20 miles north of Scarborough, but there is no record of Anne or the Robinson family she worked for as a governess, visiting it during her annual sojourns to the 19th century’s most fashionable seaside resort.

I, however, visited it this weekend and was lucky enough to visit a replica of Cook’s Endeavour. There were other ships to see as well, including a sailing replica of HMS Pickle, a small top sail schooner that was part of the vast Battle of Trafalgar fleet that saw the death of Admiral Lord Nelson in October 1805.

The Pickle was small but speedy, and nearing the English coast it spotted a fishing boat and passed on the news of the great war heroes death. The boat turned around and headed back into its port, and soon the whole of the town knew. A solemn crowd gathered to hear the news proclaimed from the Union Hotel on Chapel Street, and they then marched to nearby Madron Church. This was the first town in England to hear of Nelson’s death, and it was the Cornish town of Penzance. The Chapel Street proclamation, still re-enacted annually, was just doors from a home in which lived, among others, Maria and Elizabeth Branwell, who would raise the Brontë children as mother and aunt. Given the prominence of the Branwells in Penzance society, it is certain that these two women would have taken part in the march of 1805.

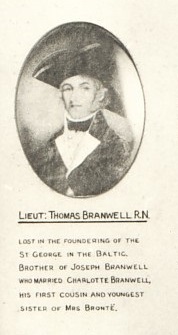

One member of the Branwell family had an even closer connection to the sea. Thomas Branwell was cousin to Maria and Elizabeth and rose rapidly in the ranks after joining the Royal Navy. By 1811 he had reached the heights of First Lieutenant on board the HMS St. George but in December of that year tragedy struck, as recorded in the Navy Chronicle:

‘The St. George, Defence, and Cressey, kept the North Sea five days, in a dreadful gale from the W.N.W. west and south; but, at length, had to combat with a terrible tempest from the N.W. until they were lost. The following is a list of the principal officers who were on board the St. George and Defence when those vessels were wrecked – In the St. George Admiral Reynolds, Captain Guion, Lieutenants Napier, Place, Thompson, Branwell, Dance, Tristram, Riches, and Rogers.’

Thomas Branwell’s body was one of many smashed upon the rocks of Thorsminde, Norway – now known as ‘Dead Men’s Dunes.’

Could it be that one Branwell in particular was heartbroken by this? Rumour has long said that Thomas and his cousin Elizabeth had been in love, (and after all Thomas’ brother Joseph and Elizabeth’s sister Charlotte married) and this may be why she then remained unmarried all her years. Could, years later, Aunt Branwell, in a tearful recollection, have told her nieces of how her love was killed in a shipwreck, and could this have inspired Charlotte Brontë’s ending to ‘Villette’?

Charlotte, Emily and Anne Brontë never suffered death at sea like Nelson or Lieutenant Branwell, nor suffered the privations endured by the crew of HMS Pickle, nor encountered a grisly end at the hands of angry Hawaiian islanders (Captain Cook’s fate). No, sea exploration was not for them – they took on a deeper exploration, an exploration of the very depths of the human heart, the unbreakable strength of the soul, the incredible heights of love, the anguish of pain and loss; when we open their books, we can embark on the same incredible discoveries, and with all their tragedies and triumphs it’s an endeavour greatly to be desired.

I was very surprised to see no mention of Rev’d William Scoresby Jr. in this article on James Cook — not only were he and his father the greatest Whitby whalers of the age, but Scoresby was also Vicar of Bradford in later life, and well-known to the Brontë family. Tales of seafaring adventure could have come directly from him to the girls.

That’s a very good point – a fascinating man!