Last Tuesday I was privileged to present a talk at the stunningly beautiful Morrab Library in Penzance, where I discussed the Branwell family of Penzance and the Brontë family of Haworth. The Branwell influence can clearly be seen in Anne Brontë’s character and writing, I believe, and this is perhaps to be expected as Aunt Elizabeth Branwell was like a mother figure to Anne, sharing a room with her during her childhood. It could also be, however, that the Branwell influence was evident in Anne’s face, for as Ellen Nussey stated:

‘Anne, dear, gentle Anne, was quite different in appearance from the others. She was her aunt’s favourite. Her hair was a very pretty, light brown, and fell on her neck in graceful curls. She had lovely violet-blue eyes, fine pencilled eyebrows, and clear, almost transparent complexion.’

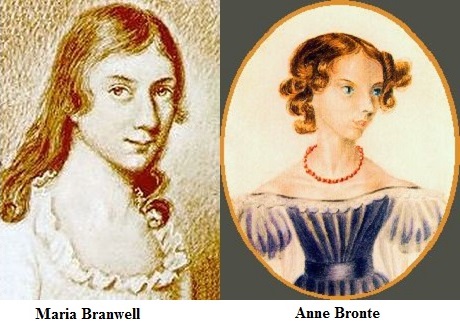

Could it be then that Anne had inherited the Branwell looks from her mother, whilst Charlotte and Emily had the Irish appearance of the Bruntys, and could this be a reason that her aunt felt so drawn to her? Certainly there seems to be some similarity, to my eyes, between the image of Maria Branwell drawn in Penzance in 1799 and this picture of a young Anne drawn by Charlotte Brontë over thirty years later.

Undoubtedly the best known portrait of Anne Brontë was drawn by her brother Branwell when she was thirteen or fourteen years of age, as she features as the left hand figure (as we look at it) in the infamous pillar portrait. It is interesting to note that Emily is close by Anne’s side in the portrait, emphasising the twin like closeness that Ellen had noted at this time, where they would invariably walk together with their arms intertwined.

Did Branwell paint another picture of Anne? The image below is commonly claimed as the only existing portrait of Emily Brontë other than in the pillar portrait. This is a surviving fragment of a lost painting known as the ‘gun group’ because this time Branwell does feature, holding a shotgun. Is it, however, a picture of Emily at all or actually another picture of Anne Brontë?

This picture of ‘Emily’ is all that survived of the completed portrait, but we do have a badly damaged early photograph of the picture, tracings used for the sketch, and an engraving based upon the photography. Here is the engraving:

It is clearly seen that the surviving portion is of the woman to the right of Branwell; it can also be seen that she bears resemblance to Anne in Branwell’s pillar portrait. The tracings seem further to confirm that Anne is the woman on the right, and Emily would have been on the far left, one of the portions that’s been lost for ever. Take a look at the engraving again, it’s been initialled, but by who? These initials were added by lifelong friend Ellen Nussey to show who sat where. Again this shows the portrait must be Anne and not Emily, but why does it continue to be attributed to Emily? Perhaps the answer is that we long, quite understandably, to have a portrait of Emily. Daphne du Maurier put it best when she wrote, in her ‘The Infernal World of Branwell Brontë’:

“Sentiment and tradition give this lovely portrait to Emily, but the resemblance to the figure of Anne in the pillar portrait group would suggest otherwise.”

There are two further disputed pictures (as well as the portraits made by her sister Charlotte) that may be of Anne Brontë, and the artist? Anne herself! Like all the Brontë siblings, Anne was a keen and fine artist, and it seems likely to me that this ‘Portrait Of A Young Woman’ is a self portrait. The exact date of composition is unknown, although we know it was painted between 1840 and 1845; this was during Anne’s stint as a governess to the Robinson family of Thorp Green Hall near York, so some speculate that it may be a picture of one of Anne’s charges. To my mind, however, this could easily be an Anne that is older than in the pillar portrait; she is now in her twenties, her face is more rounded, and she has straightened her hair but her eyes, nose and mouth look familiar. It is the beautiful, thoughtful face of Anne Brontë as a woman.

There is one more picture that I feel is of Anne, a view also shared by Christine Alexander and Jane Sellars in their brilliant book ‘The Art of the Brontës’. Dated 24th June 1842, Anne has entitled it ‘A Very Bad Picture’, which indicates of course that she was far from happy with the likeness – perhaps it was drawn for a special reason? The summer of 1842 is the time, I believe, when Anne’s love for William Weightman was at its height, and it had found itself reciprocated. Could she have been trying to draw herself to present it as a gift to the assistant curate who meant everything in the world to her? Her left arm looks strangely larger than we would expect, but her right arm is hidden, why is this? The simple answer is that Anne drew this picture from her reflection in a mirror; her left arm is closer to the mirror while the right hand out of view is drawing the picture itself.

We see Anne Brontë and her family at a distance now of course, and that, and this mirror drawn self portrait, brings to my mind the words of St. Paul in his magnificent ‘Hymn To Love’:

‘Love never fails. But where there are prophecies, they will fail; where there are tongues, they will cease; where there is knowledge, it will vanish away. For we know in part and we prophesy in part. But when that which is perfect has come, then that which is in part will be done away. When I was a child, I spoke as a child, I understood as a child, I thought as a child; but when I became a man, I put away childish things. For now we see in a mirror, darkly, but then we shall see face to face. Now I know in part, but then I shall know just as I also am known. And now abide faith, hope, love, these three; but the greatest of these is love.’

Looking at these pictures of Anne Brontë can be thrilling, but after all, we only see her through a glass, darkly. When we pick up her books, however, we get a real glimpse into her heart and soul – and then we can see and know her face to face, and love her all the more for it.

Have a look at my paper, ‘the Pillar Portrait Reconsidered’ (vol 35, 2010, issue 3) where the identity of the lefthand figure is queried, and some evidence provided that Mrs Gaskell’s memory of the painting may be flawed (knowing that Emily was the tallest), and a possible copy of a pencil portrait of Emily shows a strong resemblance to the left hand figure.

Lovely post, Nick, and I tend to agree with you concerning the different portraits. Although, I hadn’t thought about the last one being a self-portrait – a mid-nineteenth century selfie!

The last paragraph is stunning!

Hi Nick, a good article, as always, but I have one question:

if you are convinced that the gun group picture is Anne, why did you use it as a cover for your recent book about Emily?

Sorry, bu I’m still not convinced that this is Anne! For me it is still a picture of Emily.

Kind regards

Marina

Marina

Hi Marina,

A good question – the publisher chose the cover illustration, and as most people think it’s of Emily I was fine with it being used. I personally think it’s Anne, but I could well be wrong!