Anne Brontë died tragically young, aged just 29 (whatever it may say on her Scarborough tombstone), but the last week has marked the anniversary of the death of a man who could only have dreamt of reaching such an age. Thomas Chatterton, as we shall see, has a Brontë connection, he was a great poet, a great dreamer, he cheated the experts of his day but he couldn’t cheat fate, and he died on 24th August 1770 – he was just 17 years old.

Chatterton’s story is a rather unique one from beginning to end. He was born in Bristol in November 1753, where his father, another Thomas Chatterton who wrote poetry that was in no way the equal of his son’s, was a church sexton and musician, but also a firm believer in the occult.

Chatterton senior died four months before the birth of his son, meaning that Thomas was born into complete poverty, and thrown upon the mercies of a charity school. Here he made rather peculiar progress; he failed to interact with his fellow pupils and often sat in a trance for hours at a time. When asked what he would like painted onto a bowl, he replied: ‘paint me an angel with wings and a trumpet, to trumpet my name over the world’.

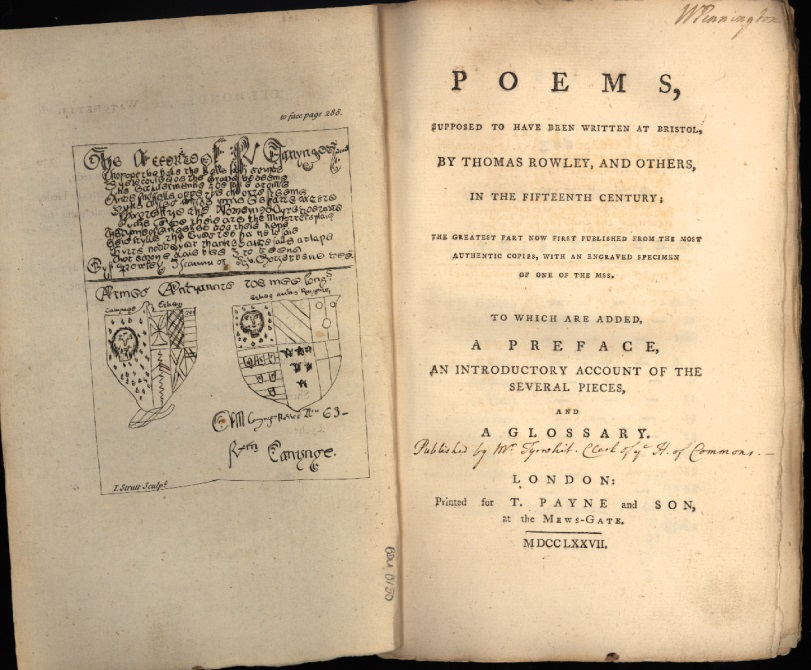

He was considered educationally backward, but as he was to show he was far from it. By the age of 11 he had begun writing incredible poetry, but what was most remarkable was that it was written in a medieval style rather than the vernacular. Chatterton loved medieval verse, and composed a succession of poems supposedly by a 15th century monk named Thomas Rowley. Despite being in his mid teens, Chatterton’s Rowleyan verse fooled much of the establishment, and Rowley was hailed as a great and newly discovered poet.

Eventually it was discovered that the Rowley poems were forgeries, and that the schoolboy Chatterton was behind the literary hoax, but undeterred the 16 year old then started writing political tracts and essays. He moved to London where he hoped to sell his writing to magazines. His work was published but he received very little money, and eventually he slipped towards starvation and poverty.

A bizarre incident occurred on the last reported sighting of Thomas Chatterton. A friend saw Chatterton walking deep in thought across Old St Pancras Churchyard (a spot I like to walk through myself on visits to London) but he failed to spot an open grave and walked right into it. The friend hauled Chatterton out, at which point he stated: ‘My dear friend, I have been at war with the grave for some time now.’

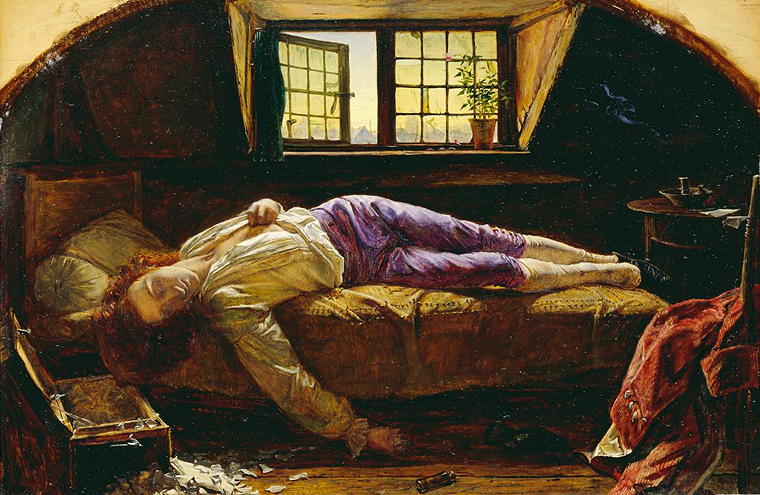

Three days later, a wealthy man named Fry visited Chatterton in his attic room in Brook Street, intending to give him financial support (Chatterton’s poverty was well known, and he often went days without eating); alas, he found the 17 year old poet dead on his bed. He had committed suicide by drinking arsenic, and by his body was a fragment of a final Rowley poem.

Chatterton must have thought he was a failure, to borrow the words of John Keats (another poet who died much younger than Anne Brontë) he would not last as ‘here lies one whose name is writ on water’. Keats was very wrong of course, and so was Chatterton to an extent. His work is still read today, but more than that he became a romantic figure for poets and dreamers everywhere, as well as a huge inspiration for the Romantic poets that followed such as Wordsworth and Shelley. This status was summed up in a portrait that has brought him everlasting fame: the 1856 painting ‘The Death Of Chatterton’ by Henry Wallis.

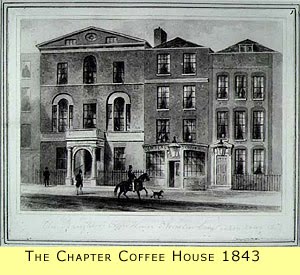

I mentioned a Brontë connection? Chatterton, in his brief and torrid spell in London mixed with the literary greats of the day. He was admitted into the circle of the likes of Oliver Goldsmith and Samuel Johnson, and where did they and Chatterton meet? The Chapter Coffee House on Paternoster Row. In the succeeding century, it was the place that Charlotte and Anne Brontë stayed in on their 1848 visit to London. Did they know that Chatterton’s shade stalked the corridors, or that he looked out onto the shadow of St. Paul’s, wondering which outcome was to be his: triumph or death?

Thomas Chatterton burned brightly at 11 and by 17 he was burnt out. He tried and failed, but his heroism is still acknowledged because he certainly didn’t fail to try. I will leave you with his poem ‘Resignation’, one of the masterpieces written in his own tongue rather than obscured by faux medievalism, and one which showed his thoughts and feelings as his end approached:

“O God, whose thunder shakes the sky,

Whose eye this atom globe surveys,

To thee, my only rock, I fly,

Thy mercy in thy justice praise.

The mystic mazes of thy will,

The shadows of celestial light,

Are past the pow’r of human skill,–

But what th’Eternal acts is right.

O teach me in the trying hour,

When anguish swells the dewy tear,

To still my sorrows, own thy pow’r,

Thy goodness love, thy justice fear.

If in this bosom aught but Thee

Encroaching sought a boundless sway,

Omniscience could the danger see,

And Mercy look the cause away.

Then why, my soul, dost thou complain?

Why drooping seek the dark recess?

Shake off the melancholy chain.

For God created all to bless.

But ah! my breast is human still;

The rising sigh, the falling tear,

My languid vitals’ feeble rill,

The sickness of my soul declare.

But yet, with fortitude resigned,

I’ll thank th’ inflicter of the blow;

Forbid the sigh, compose my mind,

Nor let the gush of mis’ry flow.

The gloomy mantle of the night,

Which on my sinking spirit steals,

Will vanish at the morning light,

Which God, my East, my sun reveals.”