We may be becoming a more secular society, but Sunday morning is still a day when many of us go to church – and it can be an energising experience, one that fills us with love and makes us think about deeper aspects of life that can so easily be lost in the hustle and bustle of the modern world.

Church going was certainly something that Anne Brontë loved, and of course church attendance as a whole was much greater in the early nineteenth than the early twenty first century. Not everyone in Haworth attended the Reverend Patrick Brontë‘s church however, far from it. St. Michael’s and All Angels at the summit of Main Street was the official Church of England church, and every household had to pay dues to the church, whether they attended it or not. This caused great anger among the Haworth dissenters, as followers of the Baptist and Wesleyan (or Methodist) faiths were known, and in fact they were greatly in the majority.

An ecclesiastical survey taken on Sunday May 30 1851 revealed that 383 people had attended the three services that day at Patrick’s church. However, 422 had attended Lower Town Wesleyan Methodist church, 424 had attended West Lane Baptist church, and 900 had attended Hall Green Baptist church, showing that only 15% of church goers in Haworth went to the official Church of England services.

Anne Brontë was undoubtedly the most religious of the Brontë sisters, and her deep love and understanding of the Bible is shown in her great novels ‘Agnes Grey‘ and ‘The Tenant Of Wildfell Hall‘. In one passage we see how Anne had read the Bible in its original Greek, and come to understand that the translation of eternal within its chapters, meaning forever, is wrong – the original meaning was actually enduring or for a long time, but not without end, not without hope. It was this that led Anne to realise that people were not damned for ever as many hardline Calvinist preachers, men such as William Carus Wilson, stated, but rather that forgiveness would come eventually, that salvation was available for all in the next world.

This belief in a loving God was, strange as it sounds today, controversial and unconventional in its time, and it’s expressed beautifully in a letter she wrote to the Reverend David Thom of Liverpool. He had been so moved by ‘The Tenant Of Wildfell Hall’, recognising a kindred spirit, that he wrote to the author. 30th December 1848 was a time of trauma for Anne, her beloved Emily had died less than two weeks earlier, and she herself was clearly now gravely ill, and yet it was on this date that she replied to Reverend Thom:

‘I have seen so little of controversial Theology that I was not aware the doctrine of Universal Salvation had so able and ardent an advocate as yourself; but I have cherished it from my very childhood – with a trembling hope at first, and afterwards with a firm and glad conviction of its truth. I drew it secretly from my own heart and from the word of God before I knew that any other held it. And since then it has ever been a source of true delight to me to find the same views either timidly suggested or boldly advocated by benevolent and thoughtful minds; and I now believe there are many more believers than professors in that consoling creed… I thankfully cherish this belief; I honour those who hold it; and I would that all men had the same view of man’s hopes and God’s unbounded goodness as he had given to us.’

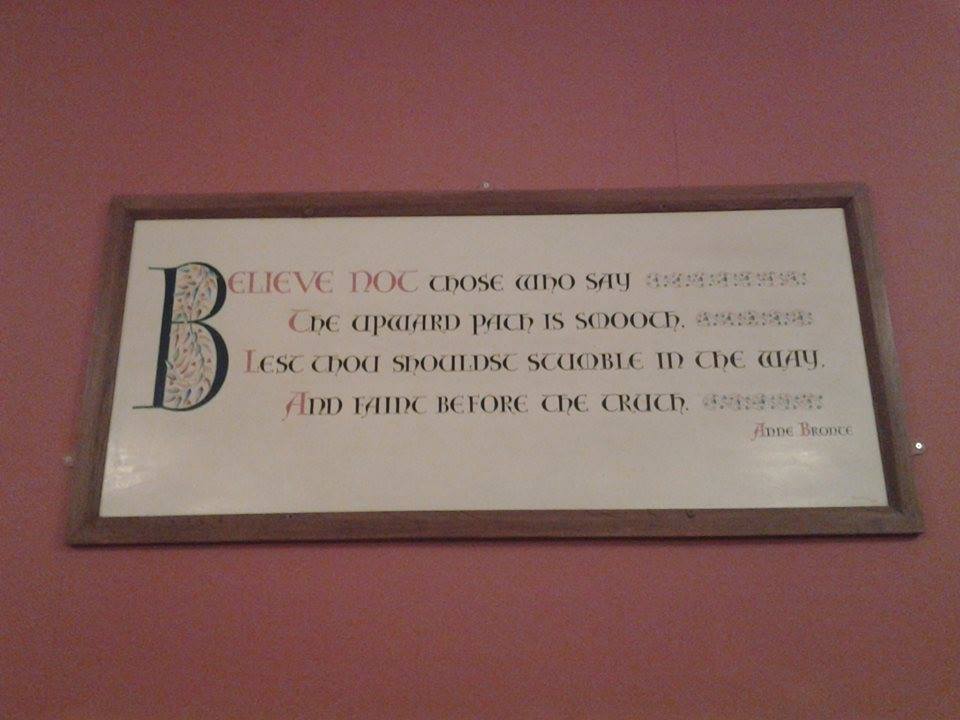

This doctrine of love and beauty and salvation was at the heart of all Anne believed and did, and it’s also at the heart of her wonderful poem ‘The Narrow Way’ (which has itself been adopted as a hymn by the Moravian church). I will leave you with this poem of Anne’s, and whatever your beliefs I wish you a blessed, happy, reflective and love filled Sunday:

‘Believe not those who say

The upward path is smooth,

Lest thou shouldst stumble in the way

And faint before the truth.

It is the only road

Unto the realms of joy;

But he who seeks that blest abode

Must all his powers employ.

Bright hopes and pure delights

Upon his course may beam,

And there amid the sternest heights,

The sweetest flowerets gleam;

On all her breezes borne

Earth yields no scents like those;

But he, that dares not grasp the thorn

Should never crave the rose.

Arm, arm thee for the fight!

Cast useless loads away:

Watch through the darkest hours of night;

Toil through the hottest day.

Crush pride into the dust,

Or thou must needs be slack;

And trample down rebellious lust,

Or it will hold thee back.

Seek not thy treasure here;

Waive pleasure and renown;

The World’s dread scoff undaunted bear,

And face its deadliest frown.

To labour and to love,

To pardon and endure,

To lift thy heart to God above,

And keep thy conscience pure,

Be this thy constant aim,

Thy hope and thy delight,

What matters who should whisper blame,

Or who should scorn or slight?

What matters – if thy God approve,

And if within thy breast,

Thou feel the comfort of his love,

The earnest of his rest?’