The 24th of September is a solemn day for Brontë lovers, as it marks the anniversary of the death of Patrick Branwell Brontë on that day in 1848. That itself was a significant loss to his family and posterity, if we look beyond the two dimensional ‘ogre’ often portrayed. It is even more significant, and moving, however, when we consider that it was the first of three sibling deaths in little over eight months, and that all too soon his sisters Emily and Anne Brontë would follow him out of this world.

Branwell Brontë was a complex man who undoubtedly had serious issues that contributed to his decline and death. He was an alcoholic and frequently throughout his life he was also addicted to opium (of which heroin is the modern day equivalent) and laudanum, the tincture of opium mixed with spirits that was cheap, easily available in Haworth, and terrifyingly addictive and powerful. Like Lord Lowborough in Anne’s ‘The Tenant Of Wildfell Hall‘ he managed to beat this addiction by going ‘cold turkey’ but he also returned to its embrace. Branwell’s addictions, and his recurring boutsof depression and mental anguish, were in all probability linked to issues relating to the childhood losses he suffered – the devastating early deaths of his mother and then his eldest sisters Maria and Elizabeth; we should not, however, let the form of his end cloud our impression of his life as a whole.

Branwell could be a happy, generous brother – it was he after all who shared the gift of twelve toy soldiers with Charlotte, Emily and Anne in July 1826, a gift that was to prove pivotal in unlocking the childhood creativity within the Brontës. Patrick had brought other gifts for his daughters, including a paper doll for Anne, but the soldiers he bought for his son were shared immediately among his siblings as a young Branwell himself remembered:

‘I carried them [the soldiers] to Emily, Charlotte and Anne. They each took up a soldier, gave them names, which I consented to, and I gave Charlotte Twemy, to Emily Pare, to Anne Trot to take care of them, although they were to be mine and I to have the disposal of them as I would.’

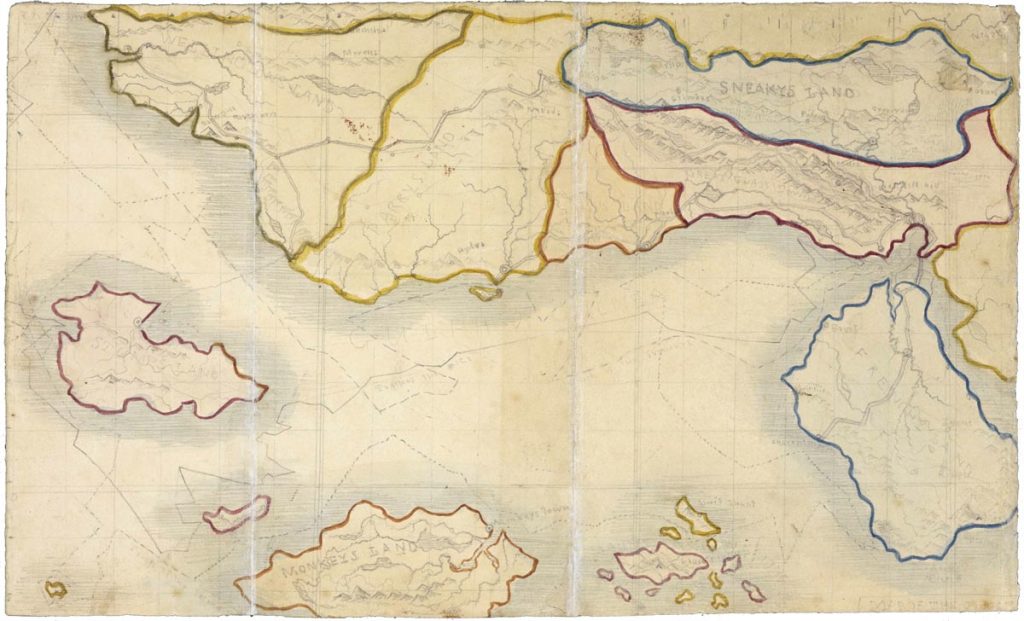

These twelve soldiers became the young men who populated their childhood world of the Great Glasstown Confederacy, which in turn became Angria. This is the land behind the incredibly tiny and intricate little books that can still be seen at Harvard University and in the Brontë Parsonage Museum today. It is Branwell that took the lead role in this early creative outburst, as evidenced by the initial name of their books being ‘Branwell’s Blackwood Magazine.’

Branwell was possibly the most enthusiastic early poet of the four remaining siblings, and he was not lacking in ambition, as the conclusion to his letter to Blackwood’s Magazine of Edinburgh in December 1837 showed:

‘Now, sir, do not act like a commonplace person, but like a man willing to examine for himself. Do not turn from the naked truth of my letters, but prove me – and if I do not stand the proof, I will not further press myself upon you. If I do stand it, why, you have lost an able writer in James Hogg, and God grant you may gain one in Patrick Branwell Brontë’

Branwell was also not lacking in talent as a poet, and we do well to remember that Branwell was the first of the Brontë siblings to find themselves in print (Anne was the only other sibling who had her poetry published without paying for it). His verse appeared in a number of local publications under the pseudonym of ‘Northangerland’, a complex character from the Angrian saga, one readily identified with by his creator. Under this guise his work appeared in publications ranging from the Yorkshire Gazette and Leeds Intelligencer to the Halifax Guardian which on June 5th 1841 published his poem ‘Heaven an Earth’.

Branwell had twelve poems published by the Halifax Guardian alone, and this was no mean feat as they took their poetry very seriously, and the standard was very high. Reading Branwell’s poetry today reinforces the impression of a good poet with a real love of verse. It is sad, therefore, that by 1846 his addictions made him unable to be considered for inclusion within ‘Poems by Currer, Ellis and Acton Bell’.

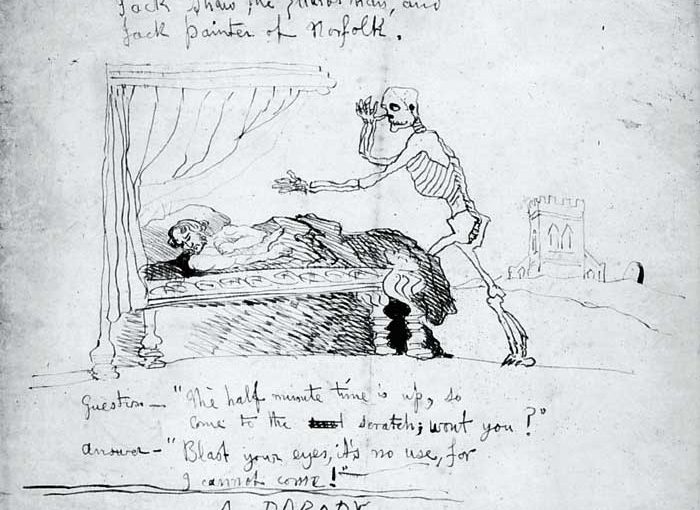

Branwell was a talented man in many areas; a skilled musician from an early age, a fine artist, and a loving brother who drew sketches for his baby sister Anne – a kindness she never forgot. He could write with both hands at once, composing a Greek letter with his left hand and a Latin letter with his right – an incredible testimony to the talents that lay within him. If Branwell had reached creative maturity I have little doubt that the results would have been brilliant, and with modern day medicines, treatments and understanding he could have lived a longer and productive life. As it is, the last creation we have from Branwell’s hands is entitled ‘A Parody’ and shows himself being visited by death (it’s at the head of this post.)

What is, perhaps, strange, however, is that it was not his addictions which killed Branwell, but tuberculosis, the same consumptive condition which would wrest Emily and Anne away too. Haworth was a sickly village at this time, with rampant epidemics of the likes of cholera and typhoid, but tuberculosis was relatively rare – it was a disease of densely packed urban areas.

It seems likely that either Anne or Charlotte inadvertently brought the disease back from their voyage to London in July 1848. Branwell, his immune system seriously weakened by his addictions, succumbed first. Kind, caring Emily would no doubt have nursed Branwell, even if she was ordered not to, and so she caught the disease from her brother and in stoic silence she perished next. Anne was next to fall, like a series of dominoes whose conclusion is certain once the first one has been pushed.

It is a terrible sequence for literary lovers, a tragedy for Brontë fans, and a disaster for Patrick and Charlotte Brontë and for those across the world who to this day hold the Brontë family close in their hearts. But let us not mourn, but rather let us remember the kind, talented brother Branwell could be and the great works that his early help and support led to. In his last moments Branwell showed his true character once more, saying ‘amen’ to his father’s prayers, and with a great strength of will rising shakily to his feet and dying in Patrick’s arms. It was the death of a hero, if a tragic one. Perhaps, as so often, the case Emily Brontë sums it up best in her conclusion to her 1839 poem ‘Stanzas To ‘:

“Do I despise the timid deer,

Because his limbs are fleet with fear?

Or, would I mock the wolf’s death-howl,

Because his form is gaunt and foul?

Or, hear with joy the leveret’s cry,

Because it cannot bravely die?

No! Then above his memory

Let Pity’s heart as tender be;

Say, ‘Earth, lie lightly on that breast

And, kind Heaven, grant that spirit rest!'”