What’s in a name, as a famous writer once said? On this day, the 3rd of October, in 1802 a 25 year old Irishman was recorded in the register of St. John’s College, Cambridge, where he’d arrived two days earlier. He was named ‘Patrick Bronte‘ but that was the first, but certainly not the last, time that would be used.

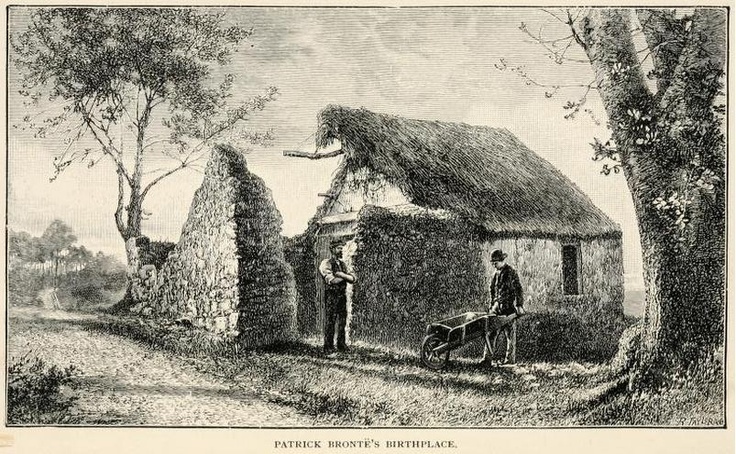

Patrick was born on the 17th March 1777 in Drumballyroney, County Down, and named after the patron saint whose feast fell on that same day, but at that time his family name was Brunty, or possibly Prunty or even O’Pronntaigh, and his parents Hugh and Alice could never have imagined the life that lay ahead of him.

The expected course of Patrick’s life would have seen him become a farmer or a labourer on the land (although he had also been taking weaving lessons) but from his earliest days he displayed remarkable talents and, most importantly, a love of reading and learning. The story goes that a local minister, Andrew Harshaw, heard the young child Patrick reading aloud ‘Paradise Lost’ by John Milton, and was so impressed that he offered to provide the boy with free tuition in the early hours of the morning, so that he could continue his weaving work as before.

Patrick was a rapid learner and a brilliant scholar, so much so that, whilst still in his teens, he was made head teacher of Glascar Hill Presbyterian Church School thanks again to Harshaw’s auspices. His time at Glascar, however, soon came to an end when the school was disbanded, but Harshaw then secured his protege a job at Drumballyroney school and the post of tutor to another local priest, Thomas Tighe.

In our lives moments happen that seem insignificant at the time: we go somewhere, do something, or meet somebody, and only later do we realise with hindsight that it was that second which changed our life forever. This was such a moment in Patrick’s life. Thomas Tighe was not only a priest, he was from a very wealthy family, and he too was impressed by Patrick’s abilities and passion for education and the scriptures.

Tighe himself had been educated at St. John’s, Cambridge and had also been a fellow of Peterhouse College, and it was under his tuition that Patrick learnt the Greek and Latin he would need to pass the Cambridge entrance exams. By 1802 he was ready and able to take that step, and Tighe himself recommended Patrick to his old college, St. John’s, as well as subsiding his entry. Tighe, then, was a philanthropist who was willing to spend his own money to help the church secure what he knew would be a fine new minister. He also, of course, secured a future that would lead to the Brontë novels we know and love today.

So why do we not laud Charlotte, Emily and Anne Prunty today? We have to return to the register of St. John’s from 216 years ago. On 1st October, the Admissions Register recorded:

“1235 Patrick Branty Ireland Sizar Tutors: Wood & Smith”

It seems that Patrick’s accent had led the registrar to hear Branty, and so it was recorded (a sizar, by the way, was a student who was being sponsored or paying reduced fees). Two days later, Patrick appears again as he takes up his official residence at the college. Once again he is recorded as ‘Branty’ but this is crossed out and it then reads “Patrick Bronte’; Patrick has obviously corrected the registrant, but in so doing has invented a new surname for himself.

It could be that Patrick thought that ‘Branty’ sounded too obviously Irish at a time when anti-Irish sentiment ran high in England. It may also be that he thought its Irishness would bring with it Catholic connotations, hardly ideal for a man taking his first steps towards a Church of England career.

Brontë is also a rather grand sounding name, and helped to mask the bearer’s humble origins. The name became grander when it eventually acquired the diaeresis, the two dots above the letter e, with which we are all familiar today. Patrick often used a plain ‘e’, and in their early years the surname frequently used the French accented ‘é’. Only later in their lives was the ‘Brontë’ we know today uniformly adopted by his children.

His excellent knowledge of both Latin and Greek, thanks to Reverend Tighe, meant that Patrick was well aware that ‘bronte’ means thunder in that ancient language, which is sure to have impressed his fellow students who all spoke the classical languages as well as they spoke English. Patrick was also aware that one of his heroes, Admiral Horatio Nelson had been made Duke of Brontë in 1799, a castle and village on Sicily, by King Ferdinand III of the Two Sicilies in thanks for his valiant actions against Napoleon and his fleet.

It was a noble name, a grand sounding name, a thunderous name, and Patrick adopted and then wore it for the rest of his days like a suit of the finest cloth, cut from his own imagination.

By a strange coincidence, a similar change of surname happened with the Brontë siblings’ maternal forebears, the Branwell family of Penzance, Cornwall. It was only in the generation of Maria and Elizabeth Branwell that this surname was adopted, as before that they had been the Bramwells, and before that the Brammels and Brambles.

I’m off now to read a book by one of the Branty sisters. It doesn’t have the same ring does it? ‘That which we call a rose by any other name would smell as sweet’ said William Shakespeare, but a certain Reverend knew that names can have much more import than that. Well done Patrick on your wise choice!

I put this in earlier, but I don’t think it got through. I’m now registered with WordPress (after a struggle), so hoping for better luck this time..

My only quibble with the above article is that Brontë meaning “thunder” is Greek, not Latin. I can say this with confidence having gained a GCE in Latin back in the 1950s – and although the school did start a Greek class it only lasted a short while, but we did learn the work for “thunder”.

Hi Roy, thank you very much for the clarification, I will amend the post now!