This week saw the 2018 renewal of National Poetry Day, and it even encouraged me to write my first poems in many years. I discovered what I had long forgot, that writing poetry can be fun, but it can also be empowering. Some people turn to the writing of poetry to look deep inside themselves, using it as a journal to express powerful thoughts and painful memories, and through the writing of verse they achieve understanding or peace, and this is how it was to Anne Brontë too, as she revealed in ‘Agnes Grey‘:

“When we are harassed by sorrows or anxieties, or long oppressed by any powerful feelings which we must keep to ourselves, for which we can obtain and seek no sympathy from any living creature, and which yet we cannot, or will not wholly crush, we often naturally seek relief in poetry.”

Anne knew all about long oppressing powerful feelings which she kept to herself, and it’s for that reason that she wrote poetry from her earliest days until her last. Anne was especially close to her sister Emily Brontë, and in their childhood they created a fantasy world known as Gondal, writing huge amounts of prose and poetry on the subject, and creating a complex web of characters and events. Alas, none of the prose remains but we do still have a large number of their Gondal poems. They are incredibly accomplished for young minds, and often talk of grand adventures, romances thwarted, and prisoners locked in dark dungeons.

When away from the influence of Emily, for example when at Roe Head school in Mirfield or as governess to the Ingham or Robinson families, Anne wrote poetry that was much more personal to her. Occasionally she wrote poetry that was ostensibly said by Gondal characters, but which really spoke of her own feelings, as in the beautiful yearning of ‘Home’:

“How brightly glistening in the sun

The woodland ivy plays!

While yonder beeches from their barks

Reflect his silver rays.

That sun surveys a lovely scene

From softly smiling skies;

And wildly through unnumbered trees

The wind of winter sighs:

Now loud, it thunders o’er my head,

And now in distance dies.

But give me back my barren hills

Where colder breezes rise;

Where scarce the scattered, stunted trees

Can yield an answering swell,

But where a wilderness of heath

Returns the sound as well.

For yonder garden, fair and wide,

With groves of evergreen,

Long winding walks, and borders trim,

And velvet lawns between;

Restore to me that little spot,

With grey walls compassed round,

Where knotted grass neglected lies,

And weeds usurp the ground.

Though all around this mansion high

Invites the foot to roam,

And though its halls are fair within –

Oh, give me back my HOME!”

Here we read, so often repeated in Anne’s writings, the desire to be back in the rugged country she so loved.

It was a chance discovery of Emily’s poetry by Charlotte that launched the literary career of the sisters and changed our world forever. Here is how Charlotte later remembered the discovery:

“One day, in the autumn of 1845, I accidentally lighted on a manuscript volume of verse in my sister Emily’s handwriting. Of course, I was not surprised, knowing that she could and did write verse: I looked it over, and something more than surprise seized me, – a deep conviction that these were not common effusions, nor at all like the poetry women generally write. I thought them condensed and terse, vigorous and genuine. To my ear, they had also a peculiar music – wild, melancholy, and elevating. Meantime, my younger sister (Anne) quietly produced some of her own compositions, intimating that since Emily’s had given me pleasure, I might like to look at hers. I thought that these verses too had a sweet sincere pathos of their own.”

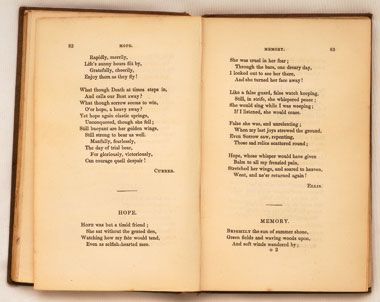

Emily, predictably, was furious at this discovery. An intensely private woman, she hated the thought of people reading her words and seeing into her soul. It took two days of arguing to win her round, and it was then that the sisters agreed to publish a collection of their poetry: “Poems by Currer, Ellis, and Acton Bell.”

The book received some pleasing reviews but failed to sell, but the sisters had caught the publishing book and embarked on a new project to write novels. We all know what happened after that. Emily is often regarded as the premier Brontë poet, but it was Anne who enjoyed commercial success, being the only sister to have her poetry published in periodicals. Friend of the family Ellen Nussey recalled one such incident:

“I observed a slow smile spreading across Anne’s face as she sat reading before the fire. I asked her why she was smiling, and she replied: ‘Only because I see they have inserted one of my poems.'”

There is one large section of Anne’s poetry that we cannot overlook, her love poems. From the date William Weightman arrived as curate at Haworth, the formulaic Gondal love poetry became something very different, something real. After his untimely death, she wrote poem after poem about loss and mourning. A coincidence or something much deeper? Was this the poetry that reveals those ‘powerful feelings we must keep to ourselves’? I think if we look at Anne’s words, and look into our own hearts, we can find an answer. So whether you’re feeling happy or sad in the week to come, perhaps you could follow Anne’s example and let it inspire you into the creation of poetry!