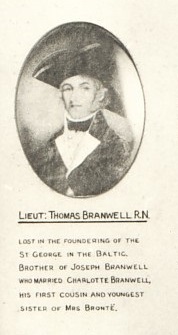

It’s time for a rare Monday blog post, as today marks the 121st anniversary of a date that is well worth remembering: the death of an unsung heroine of the Brontë story, Ellen Nussey. Earlier posts have examined her role as the great friend of Charlotte Brontë, and looked at how she saved the Brontë legacy for us all to enjoy.

Ellen Nussey died at Brookroyd House in Birstall (that’s it today at the top of this post), in the West Riding of Yorkshire, on 26th November 1897. Ellen was eighty years old and though she outlived all the Brontë siblings by more than four decades, she never forgot them. To celebrate this remarkable woman, today’s post will simply relate some of the letters sent to her by Charlotte, Emily and Anne Brontë, beginning with extracts from five of the hundreds of letters sent from Charlotte Brontë to her beloved Nell:

“Don’t deceive yourself by imagining that I have a real bit of goodness about me. My darling if I were like you I should have my face Zion-ward though prejudice and mist might occasionally fling a mist over the glorious vision before me, for with all your single-hearted sincerity you have your faults. But I am not like you. If you knew my thoughts, the dreams that absorb me, and the fiery imagination that at times eats me up and makes me feel Society, as it is, wretchedly insipid, you would pity and I dare say despise me. But Ellen I know the treasures of the Bible, I love and adore them. I can see the Well of Life in all its clearness and brightness; but when I stoop down to drink of the pure waters they fly from my lips as if I were Tantalus. I have written like a fool.” (10 May 1836)

*

“If I like people it is my nature to tell them so and I am not afraid of offering incense to your vanity. It is from religion that you derive your chief charm and may its influence always preserve you as pure, as unassuming and as benevolent in thought and deed as you are now. What am I compared to you? I feel my own utter worthlessness when I make the comparison. I’m a very coarse common-place wretch! Ellen, I have some qualities that make me very miserable, some feelings that you can have no participation in – that few, very few, people in the world can at all understand. I don’t pride myself on these peculiarities, I strive to conceal and suppress them as much as I can. But they burst out sometimes and then those who see the explosion despise me and I hate myself for days afterwards.” (October 1836)

*

“If I could always live with you, and daily read the Bible with you, if your lips and mine could at the same time, drink the same draught from the pure fountain of Mercy – I hope, I trust, I might one day become better, far better, than my evil wandering thoughts, my corrupt heart, cold to the spirit, and warm to the flesh will now permit me to be. I often plan the pleasant life which we might lead together.” (5 December 1836)

*

“From what I know of your character – and I think I know it pretty well – I should say you will never love before marriage. After that ceremony is over, and after you have had some months to settle down, and to get accustomed to the creature you have taken for your worse half – you will probably make a most affectionate and happy wife – even if the individual should not prove all you should wish… I have told you so before, and I tell it you again. Mediocrity in all things is wisdom – mediocrity in the sensations is superlative wisdom.” (20 November 1840)

This letter, in which Charlotte gives advice to Ellen on a proposal she had received (from a Reverend Osman Vincent) is particularly interesting, as whilst Ellen never married the advice Charlotte gives is exactly the course she herself followed 14 years later when she married Reverend Arthur Bell Nicholls.

*

“Oh Lord Nell, I’m in danger sometimes of falling into self-weariness – I used to say and to think in former times that you would certainly be married – I’m not so sanguine on that point now. It will never suit you to accept a husband you cannot love or at least respect… Well Nell if you are destined to be an old maid I don’t think you will be a repining one – I think you will find resources in your own mind and disposition which will help you to get on.” (19 January 1847)

*

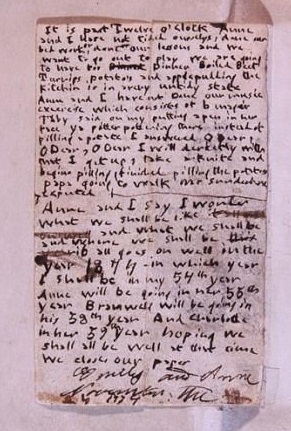

“Dear Ellen, Arthur complains that you do not distinctly promise to burn my letters as you receive them. He says you must give him a plain pledge to that effect – or he will read every line I write and elect himself censor of our correspondence. He says women are most rash in letter-writing – they think only of the trustworthiness of their immediate friend – and do not look to contingencies.” (31 October 1854)

Thankfully for posterity, of course, Ellen didn’t burn the letters, although she did write to Arthur saying that she would do as long as he promised not to censor Charlotte’s letters.

*

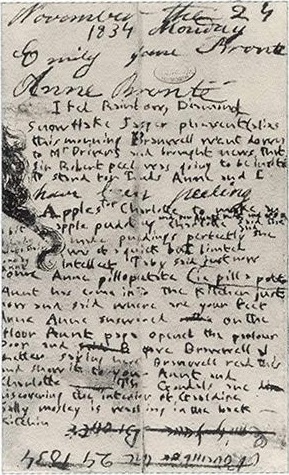

Whilst initially Charlotte’s friend, after they met at Roe Head School in Mirfield, Ellen became friends with all the Brontë family – even the usually reserved Emily Brontë whose two extant letters are both addressed to Ellen, the second of which is below:

“Dear Miss Ellen, if you have set your heart on Charlotte staying another week she has our united consent; I for one will take everything easy on Sunday – I’m glad she’s enjoying herself: let her make the most of the next seven days & return.” (16 July 1845)

*

The measure of Ellen’s true worth is shown by the loving and affectionate way that she treated Anne Brontë in her final days; on her last morning it was Ellen who carried the dying Anne downstairs so she could sit in a window, and Anne’s final wish was that Ellen would take her place and be a sister to Charlotte. Anne’s last, moving, letter was addressed to Ellen Nussey, asking her to accompany her to Scarborough:

“I know, and every body knows that you would be as kind and helpful as any one could possibly be, and I hope I should not be very troublesome. It would be as a companion not as a nurse that I should wish for your company, otherwise I should not venture to ask it.” (5 April 1849)

*

So what do the letters to Ellen from the Brontë sisters show us? That she was kind, loyal, loving, unflinching and trustworthy. What greater qualities could we wish for in a friend? We should remember Ellen Nussey fondly on this day, for she was not only a friend to the family within Haworth Parsonage, she was a friend to us all.