This weekend and on Monday people across the country will be gathering around bonfires – and it is likely that on the 5th November a certain Haworth family did the same: the Brontës. In fact, until the Observation of 5th November 1605 Act was repealed in 1859 all churches had to hold a thanksgiving service, accompanied by bonfire, to celebrate the foiling of Catesby and Fawkes’ plot to blow up parliament, and attendance was compulsory by law. The 1842 celebrations would have been rather more muted for the Brontës, however, as the previous week had seen the death and burial of an integral part of the family: Aunt Elizabeth Branwell.

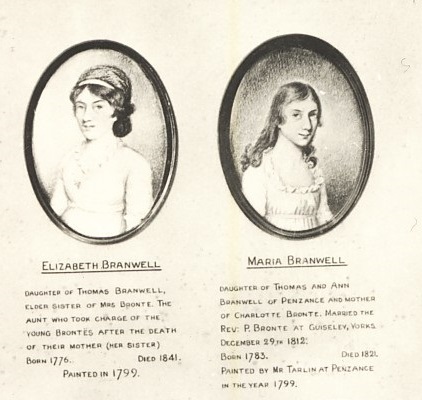

In previous blogs we’ve looked at how Aunt Branwell became a second mother to the Brontës, and how she was especially close to Anne. In short, Elizabeth left behind a life of ease and sunshine in Penzance, Cornwall when in 1821 she travelled over 400 miles to Haworth to nurse her dying sister Maria. After Maria’s death she could have returned to Cornwall but stayed to raise her nephew and five nieces as best she could. It was a huge sacrifice in many ways, and my latest book ‘Aunt Branwell and the Brontë Legacy‘ looks at how without Elizabeth’s emotional and financial support we wouldn’t have any of the Brontë books we love today.

In today’s blog we look at Aunt Branwell’s passing and burial, and what it says about this woman who deserves to be remembered and respected. There is much evidence to say that Aunt Branwell was far from the austere, humourless woman that she is sometimes portrayed as, but we need look no further than the tribute from her nephew Branwell Brontë to show her true character and worth. If Elizabeth really was strict we could have expected her to be at loggerheads with the independent spirited Branwell, but the truth was very different.

On 25th October 1842, Branwell wrote a moving, despairing letter to his friend Francis Grundy:

‘I have had a long attendance at the deathbed of the Rev. William Weightman, one of my dearest friends, and now I am attending at the deathbed of my aunt, who has been for twenty years as my mother. I expect her to die in a few hours… excuse this scrawl, my eyes are too dim with sorrow to see well.’

Branwell remained faithfully by his Aunt’s side day and night, until she passed from this world on 28th October 1842, after which he again wrote to Grundy:

‘I am incoherent, I fear, but I have been waking two nights witnessing such agonising suffering as I would not wish my worst enemy to endure; and I have now lost the guide and director of all the happy days connected with my childhood.’

We need no better tribute than this, the facts are plain to see: Elizabeth Branwell, whatever Elizabeth Gaskell may later write, was loved by her nephew and nieces. She was not only there while they had a happy childhood, she was the person who gave them a happy childhood, against all the odds. Incidentally, of course, this also shows another side of Branwell Brontë’s character often overlooked – he could be loyal and loving.

Aunt Branwell died of a blockage of the bowel, and her dreadful torment must have been reminiscent to her brother in law Patrick of the final illness and death of his beloved wife Maria. It must have been another huge blow to Patrick as he and Elizabeth had been close since her arrival in Haworth, and had become like brother and sister themselves. Patrick’s great admiration for her was revealed in a letter to his friend Reverend Buckworth when he wrote of the aftermath of Maria’s death:

‘Her sister, Miss Branwell, arrived, and afforded great comfort to my mind, which has been the case ever since, by sharing my labours and sorrows, and behaving as an affectionate mother to my children.’

Elizabeth Branwell’s final illness, thankfully, was not as prolonged as her sister’s had been, and it had come on suddenly, as she had enjoyed robust health until that point, but nevertheless she had made preparations for after her death. She had made a will on 20th April 1833, and her legacy gave four of her nieces the liberty and support they needed to become writers. The Branwells were a relatively wealthy family, and the substantial amounts Elizabeth left to Charlotte, Emily and Anne Brontë allowed them to pay for the publication of ‘Poems by Currer, Ellis and Acton Bell’, and also for the publication of ‘Wuthering Heights’ and ‘Agnes Grey’; without the money from their aunt’s will, there is simply no way they could have afforded these sums, and the Brontë story as we know it today would have remained untold.

I say four nieces, because in her will Elizabeth supported another niece – and one whose story was even more tragic than that of her Haworth cousins.

Elizabeth Branwell had many nieces still in Cornwall, but she chose only one other to support in her will: Eliza Kingston, daughter of Elizabeth and Maria’s elder sister Jane. Jane had emigrated to America with her husband John Kingston, but their marriage was not a happy one. She left America to return to England having to leave three children behind with John, but with her she brought a baby born in Baltimore, Maryland – Eliza. Surely in Jane we can see a prototype of Helen, the tenant of Wildfell Hall?

Elizabeth Branwell supported both Jane and her daughter through their struggles, and realised that her American born niece needed help more than her Cornish brethren – and so it was that Eliza Kingston was left an equal quarter share along with Charlotte, Emily and Anne.

We have a number of letters by Eliza, and they are a fascinating correspondence. They show that she read the novels of her Haworth cousins, and also that Patrick Brontë wrote to her in Penzance until the last year of his life. They also show her terrible, tragic decline. Eliza invested her inheritance in Cornish tin mine shares, and at first they did well, but we read of her descent into unimaginable poverty as her fortune diminished and vanished. In a letter painful to read she writes:

‘I feel very weak at times, if I over-exert myself or do not take sufficient nourishment; I require (if I could have it) animal food every day… I cannot live so low as I used to. I was informed that it was a case of nervous debility which I knew before… there is often a cobweb (or something like it) floating before my left eye… I live in constant dread of the future… I have no prospect of a home or rooms or indeed any money to pay rent… God only knows how it will end… I sometimes feel as if my heart would break.’

It was the last letter Eliza wrote, she could no longer afford stamps; she died in an asylum in 1878 but we hear one further story of her from a distant cousin who knew her:

‘I think my mother asked Miss Kingston about Charlotte Brontë on more than one occasion. They talked about her together, and Miss Kingston spoke a good deal about what Charlotte Brontë had brought out in her works, and how she depicted characters. I have a vivid recollection of wonder that our poor cousin Eliza Jane could say such beautiful things and see so much in books, and yet look so plain and prosper so badly. Is there any record of the book she wrote, or was it only a part? Perhaps she destroyed it. She said no one would publish it.’

Here then we see that Aunt Branwell’s will helped not three, but four nieces have the financial freedom to do what they wished to do more than anything else – write a book. If only we still had Eliza’s it would surely be something special, as her letters are vivid and very reminiscent of her cousin Charlotte’s.

At the start of her will, Elizabeth Branwell left an important and very telling provision – that she wished to be buried: ‘as near as convenient to the remains of my dear sister.’

Thus it was that on the 2nd of November 1842 she was buried in the Brontë family vault at Haworth’s St. Michael’s and All Angels church, alongside her sister Maria and her nieces Maria and Elizabeth. Family meant everything to Elizabeth Branwell, and by family I mean the Brontë family. Yes, the sacrifice Elizabeth made in 1821 and in the 21 years subsequent was immense, but we must remember that she profited hugely from it.

Aunt Branwell was in her mid forties when she came to Haworth; she had money, books to read, fine weather all year round, but she had no prospects of marriage or a family of her own – she had no prospect of love, only a lonely life ahead of her. The stone floors of Haworth parsonage were so cold to her that she always wore pattens indoors, but her heart glowed. She found a family to love and who loved her back, children she could watch grow up and guide through life; it was a blessing she could never have expected to have, and it was worth much more to her than any other treasures.

So, Aunt Branwell’s legacy enriched the Brontës, but the Brontë children enriched Aunt Branwell too; as she stood by the Haworth bonfires with them she would have felt the warmth of love in her blood as well as the warmth of the flames, and what after all is more important than that? The Observation of 5th November 1605 Act is also known as The Thanksgiving Act, and so today let us give thanks to Aunt Elizabeth Branwell – we have so much to thank her for.