Children and adults alike enjoy writing diaries; they can be a great way to self-journal what you’re feeling, or to simply record a snap shot of a moment in life. A certain pair of sisters seemed to think that, and their diary entries provide us with a fascinating glimpse into their lives. What they record may often be mundane, especially compared to the incredible writing their better known for, but this mundanity shines like a diamond, because it gives us an unparalleled glimpse of two young women as they grow up, without any filter at all. I talk, of course, of Anne and Emily Brontë, and this weekend marks the 184th anniversary of their joint production of their first diary paper.

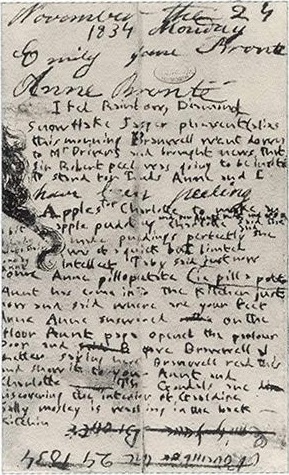

At the time of its creation, Emily Brontë was 16 and Anne Brontë, 14, and it was in this year, 1834, that we see the two sisters side by side in the famous ‘pillar portrait’ created by their brother Branwell. We know from the signatures on this diary paper that they composed it together, but the writing itself was done solely by Emily on this occasion. The handwriting in the letter was very erratic, and the spelling error strewn – so I’ve corrected these in the transcripts below to make it easier to read and understand. The succeeding years saw a remarkable improvement in Emily’s spelling and handwriting, but her genius still burned brightly from the earliest age.

Let’s take a look at its three sections:

“November the 24, 1834 Monday, Emily Jane Brontë, Anne Brontë,

I fed Rainbow, Diamond, Snowflake, Jasper, pheasant this morning. Branwell went down to Mr Drivers and brought news that Sir Robert Peel was going to stand for Leeds. Anne and I have been peeling apples for Charlotte to make an apple pudding and for Aunt’s nuts and apples. Charlotte said she made puddings perfectly and she was of a quick but limited intellect. Tabby said just now come Anne pilloputate (ie pill a potato). Aunt has come into the kitchen just now and said, ‘where are your feet Anne?’ Anne answered, ‘on the floor Aunt’. Papa opened the parlour door and gave Branwell a letter saying, ‘here Branwell read this and show it to your Aunt and Charlotte’. The Gondals are discovering the interior of Gaaldine, Sally Mosley is washing in the back kitchen.”

The first thing we see in this, their first diary paper, is Emily and Anne’s love of their pets, closely followed by their interest in the political matters of the day. 1834 was a momentous year for Sir Robert Peel, as it was in November of this year, at the very time the diary paper was being written, that he succeeded Viscount Melbourne as leader of the Tory party and became Prime Minister for the first time, after which he quickly called a general election to be held in early 1835. James Driver was a Haworth grocer, and his news of Peel’s plan to stand in Leeds (then the local constituency of Haworth in these pre-reform days) must have excited the Brontës. They had perhaps misunderstood Driver’s message, however, as Peel was the long term MP for Tamworth and never stood in Leeds. This may have been some relief to Charlotte Brontë, who, according to close friend Mary Taylor,: ‘worshipped the Duke of Wellington, but said that Sir Robert Peel was not to be trusted; he did not act from principle like the rest, but from expediency.’

We also see in this paper evidence of something people often overlook in Emily and Anne – their sense of humour and fun. Ellen Nussey later wrote of how Emily liked nothing more than laughing uproariously after playing a mischievous trick on somebody, and we read in this diary of her imitating their much loved servant Tabby Ayckroyd‘s strong Yorkshire tones – perhaps Emily used to copy her accent as well? We also read of Anne swinging her feet merrily in the air, perhaps leaning back on the rear two legs of her chair, and quickly planting them back on the floor after being noticed by Aunt Branwell.

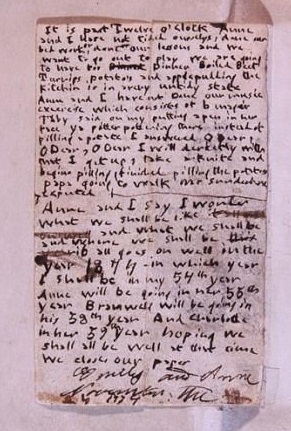

“It is past twelve o’clock Anne and I have not tidied ourselves, done our bed work or done our lessons and we want to go out to play. We are going to have for dinner boiled beef, turnips, potatoes and apple pudding; the kitchen is in a very untidy state. Anne and I have not done our music exercise which consists of b major. Tabby said, on my putting a pen in her face, ‘ya pitter pottering there instead of pilling a potate’, I answered, ‘oh dear, oh dear, oh dear, I will directly’. With that I get up, take a knife and begin pilling (finished pilling the potatoes). Papa going to walk. Mr Sunderland expected.”

Emily and Anne’s preoccupation is not on the practical side of life, making the bed (here archaically referred to as bed work) and doing the studies set by their father or aunt, but rather on indulging their creativity. They have already talked of the Gondals, their early fictitious inventions which in Emily in particular would dominate their writing life, and it is clear that they now want to be writing about them, or walking the moors together whilst in their imagination seeing them transformed into the interior of Gaaldine (a neighbouring island to Gondal that they had recently added to their stories).

Lost in deep thought, Emily waves her pen mischievously in Tabby’s face, and is scolded for doing so. Feeling repentant, Emily finally helps Tabby to peel the potatoes for their lunch. In later years this would very much become Emily’s role in the parsonage. A close bond grew between her and Tabby, and when the latter became too old or inform to do much of the cooking, Emily took to it with aplomb. It’s interesting to note the meal they were having too – contrary to the scurrilous claim set down in Elizabeth Gaskell’s life of Charlotte Brontë, the Brontë children did have meat. In fact they are here having a very tasty and nutritious meal by the standards of their time, especially as just a day before they would have had a large Sunday lunch.

“Anne and I say I wonder what we shall be like and what we shall be and where we shall be if all goes on well in the year 1874 – in which year I shall be in my 57th year, Anne will be going in her 55th year, Branwell will be going in his 58th year, and Charlotte in her 59th year; hoping we shall all be well at that time, we close our paper.

Emily and Anne, November the 24 1834”

What Emily and Anne intended to be a happy ending to their diary paper, takes on a rather melancholy air to us who look back on it with the gift of hindsight. The truth is, of course, that the whole family would be long gone by the year 1874. But, in another way, they live on always through their incredible words – and these few short lines composed in November 1834 are the very first words that we have from Emily and Anne Brontë.

The lines from their diaries and papers wondering where they will be at a future date is haunting. But as you point out, they live on, in a sense, through their writing.

Thank you for creating this blog. I have just discovered it and am working my way through. I purchased your book and can’t wait to read it. Anne Bronte has always existed in the shadow of her more well-known sisters but I found her to be a real genius of a writer.

Thank you so much, what a kind thing to say! I hope you continue to enjoy my blog (I certainly love writing it) and that you enjoy my book too!