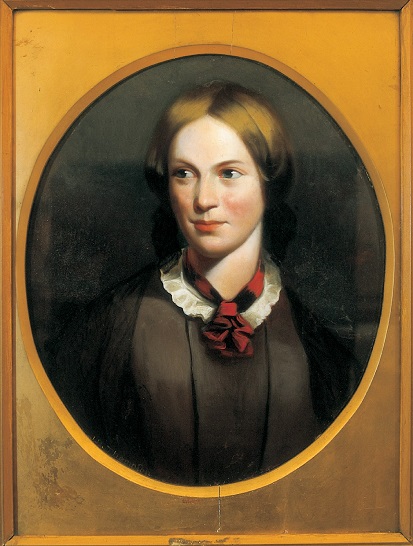

Today I’m going to relate a story that’s now very little known, indeed that had been lost within the tiny print amidst a mass of yellow tinged nineteenth century newspapers. It’s a tale full of charity and care for those less fortunate than yourself, so it’s perfect for this Christmas season. If you’re sitting comfortably I’ll begin the tale of Charlotte Brontë and the boots.

I can never stay away from the Brontë family for too long, so I may have news of two new Brontë related books next year – and that means my favourite thing of all, research! Some people might feel there’s nothing new to discover, but in fact you can sometimes find a new piece of documentary evidence that hits you right between the eyes, and illuminates further a character we know and love. That’s what happened to me yesterday as I read through some nineteenth century newspapers, and we find a story of Charlotte Brontë that is forgotten today, but which shows her studious side, her charitable side and her sense of fun.

From an 1893 copy of the Leeds Mercury comes this reminiscence from a Frank Peel of Huddersfield. He was down on his luck and quite literally down at heel, but then fate led him to a certain building in Haworth. I’ll let Frank tell the story in his own words, as he did 125 years ago:

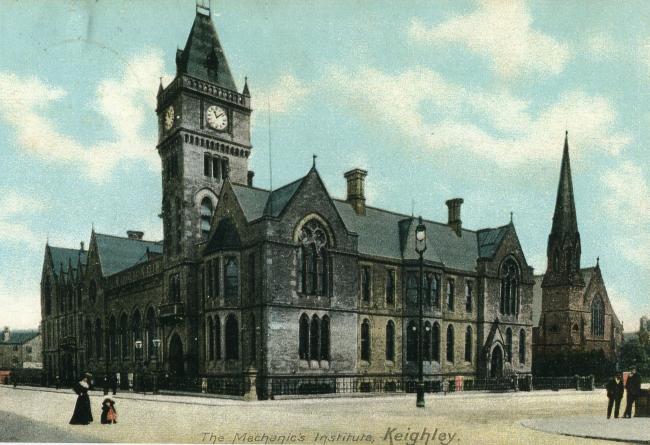

“About the month of April, 1851 (I think), I found myself one evening at Keighley, without money or friends. The factory I worked at had broken down, and, like most lads, I wandered purposelessly about to kill time. After wandering about the town till nine o’clock at night, the question where should I sleep forced itself upon my attention. Now, I had had at the Mechanics’ Institute of a neighbouring town instruction and practice in reciting pieces, and, spurred by hunger and the night air, I resolved to turn my abilities in that way into account by going into the various public-houses and offering to recite to the companies I found there, and then going round with the hat (cap in this case). The first house I went into I got sixpence for once reciting, with an offer that if I would stand on my head and sing a song they would double it. I pocketed the copper and the insult and decamped. Yet, fearing I had not enough to pay for a bed, I plucked up courage and tried in another hotel with more success, for one or two of the company assured me that if I waited upon Mr. Sam Wild, whose company was then in the town, I should be able do better than pitching in pubs.

I then sought out lodgings in a common lodging-house. Being well-dressed – that is for such lodgings – the inmates treated me very respectfully; and one, a travelling glazier, paid for my supper. In doing this he asked me what I was doing there. I told him, and also the advice I had been given about applying to Wild, and then went to bed. In the morning I found a sad mishap had befallen me – some one had gone off with my boots. I told the landlady, but she said she could not help me, so in my perplexity I consulted the glazier, who, after listening to me went out and bought me a pair of ‘pushers’ – that is, boot fronts with the leg and back cut off. To interview the theatrical manager with these on was out of the question, and on naming my difficulty to the glazier he said, after a little consideration, that he would put me into the way of getting a pair of boots. He said he was going to ‘work’ Haworth that day, and if I would carry his glass crate he would see me all right.

We trudged up the famous village, and then he pointed out a house where there was a lady – ‘Miss Charlotte’ he called her – who was ‘good for a pair of boots’ if I told her all my story. He then left me to ‘call’ the village. I felt my painful position very keenly. I durst not meet the glazier again without having seen ‘ Charlotte’ and eventually I mustered courage to knock at the door and ask for the lady. By and by a lady came, accompanied by another, younger than herself. With some difficulty I managed to tell my tale as I stood at the door, and was then invited into the kitchen and a pot of coffee and some bread and butter were put before me. By the time I had finished my breakfast the lady had returned to the kitchen and put some old boots before me, bidding me to try to fit a pair on. I did so, and found a pair which fitted pretty well. By this time the younger lady also returned into the kitchen. Both sat down, and Miss Charlotte then said, ‘I have given you breakfast, found you boots, and I am now going to talk to you a bit.’ She did talk to me, and in a way that made me wish I had never gone.

She said that in nine cases out of ten people adopted my course of life from sheer idleness or gipsy instinct, and not because they had any special talent for theatricals. Did I think I had any talent? I told her I thought I had. Would I give her a specimen? Here was a dilemma! How could I refuse after the kindness with which I had been treated? In great pain, I said I would try to comply with her request. I gave, first, ‘Young Lochinvar,’ in my best style, and then her look of motherly severity seemed to relax a little.

She then began to ask a number of questions about my family and other matters, which I answered as well as I could. Amongst other things. I told her I had relations at Cleckheaton, and described it and the neighbourhood to her. The younger lady then asked me if I knew any more recitations, and I replied I could give one or two from Shakespeare. Feeling more at ease, I at once recited one or two selections from ‘Hamlet’, without any remark being made. Miss Charlotte then asked me if I would give the dialogue between Hamlet and his mother, where the Queen says, “Do not for ever with thy veiled lids seek for thy noble father in the dust; thou know’st ’tis common, all that live must die—passing through nature to eternity.’ I complied as well I could; gave the whole scene without the ladies displaying any special interest in it, until I came to the line where Hamlet says, “I have that within which passeth show; these, but the trappings and the suits of woe,” when they both burst out into good-humoured laughter. I dared not ask the cause of this, but I suppose my looks showed my anxiety, and Charlotte said, ‘I’ve seen Hamlet played at Bradford, and they made the same mistake you have made in the word ‘suite.’ Shakespeare never could have used it in that sense – namely, a dress – but in a wider sense, ‘suite,’ pronounced ‘sweet,’ meaning that the King, Queen, and all about them were only acting the part of mourners, making their conduct match or harmonise with their supposed recent bereavement – the death of Hamlet’s father.’ I did not venture on any opinion, but said I believed it was in the book. Miss Charlotte said it was, but only showed the ignorant, shortsightedness of those who tampered with Shakespeare’s works. Other criticisms followed in a similar strain, but I have a very vague recollection of them.

After advising me to return to work and leave playing to idlers, they showed me to the door, and bid me good-morning. I should state here, to account for what follows, that the persons in the second public-house in which had I the night before been reciting were members of Mr. Wild’s company, and that they assured me that I should get an engagement with them: so that when the string of questions which Miss Charlotte put after I preferred my request for the boots began to tighten, I said I had got the engagement, and only required the boots to enable me to enter upon it at once. On leaving the house I sought my friend the glazier, and found him repairing windows just in the hollow of the village. He advised me to return to Keighley at once, and see the manager. I did so, but he had as many as the business would allow of just then. In another week, however, when they commenced the tour of the fairs, he could give me a situation for building and parade business. Unasked, he kindly gave me half a crown, and said I could go behind at night if I wished.

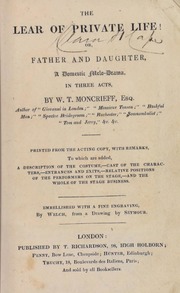

It was now getting late in the afternoon, and I sought out the members of the company, and told them the result of my application. I did go behind the scenes at night, and I am now getting at what I wish to tell you. The play was called ‘The Lear of Private Life’ – that is, a sort of domestic copy of ‘ King Lear.’ I assisted in shifting the scenes, and before the last act began the ‘ Lear’ sent me to the money-taker to get a shilling and fetch him some brandy in a pint-pot, for he was ‘nearly a croaker.’

It was a ‘grand fashionable night,’ and there were about a hundred people in the pit, and in coming from the stage to the side-door I had to pass on one side to it, and there, only just within the harden enclosure, and close to where I had to pass, was Miss Brontë and the other lady I had seen the day before at Haworth parsonage! I now felt so guilty of having told Miss Brontë a falsehood about having got the engagement that I should not have ventured to pass her if the actor’s words ‘nearly a croaker’ had not rung in my ears. In the walk for the brandy I had time to collect myself, and I decided to walk past the ladies as if I belonged to the establishment. I did so, and also made a very respectful bow to them, which they gracefully returned. I looked through the peep-hole in the wing and saw them leave soon after. It was some years after this before I learned that the lady who had given me the breakfast, the boots, and the scolding was the authoress of ‘Jane Eyre.’ I was pleased the rascal stole my boots when I learnt I had had an interview with Charlotte Brontë. – Frank Peel.”

What a beautiful story, an encounter from two centuries ago that we can now see clearly again! It’s an interesting social document as well; we see a tale of men losing their jobs and having nowhere to sleep and no money to buy food with, but isn’t it fascinating that even a man of such a fate can still recite a whole host of passages of Shakespeare from memory, and that people would pay to hear them?

Two further questions jump out at me – just whose were the old boots fit for a young working man to wear? I can only think that Charlotte must have kept some of the boots and other belongings of her brother Branwell who had died three years previously. And then, who was the ‘younger woman’ who sat alongside Charlotte and later visited the travelling show with her? Martha Brown the servant lived in the parsonage at this time and was considerably younger, but it seems hardly likely that she would sit in on the interview as well, ask questions about Shakespeare and then laugh at the man’s interpretation of a particular word. No, it seems to me that this can only have been Charlotte’s great friend Ellen Nussey who often visited the parsonage. Ellen was almost exactly a year younger than Charlotte and would have been 34 at the time of this incident, but from Frank Peel’s account it seems that she looked visibly younger than her.

Above all, we see that Charlotte was at heart a very kind and charitable woman, so much so that her reputation for it had spread outside of Haworth and into Keighley and beyond – otherwise, why would the Keighley glazier have known to send Frank to her, and even to have known her name, when in need of help?

As Christmas approaches we should think of how we can do more to help those in need at this time of year, whether it be a lonely relative or neighbour, or those who have to turn to food banks – let’s all be a bit more loving, let’s all be a bit more Charlotte!

What a wonderful story!

What a terrific post! Frank’s story in the vernacular or the times lights up the account. It is also a marvelous illustration of how personal abilities have changed – strong memories were common as was ‘personal entertainment’ i.e. reciting in pubs. I learned what ‘pushers’ were and how knowledgeable in the classics Charlotte (and the other sisters?) was. Thank you for this Seasonable Treat. Mel

LOVED IT!! I want to hear more of these!

I still believe it was Martha. She was much closer than people believe

Great story! So what new books are coming out?

Love they story it shows the sister had a kind hearts!