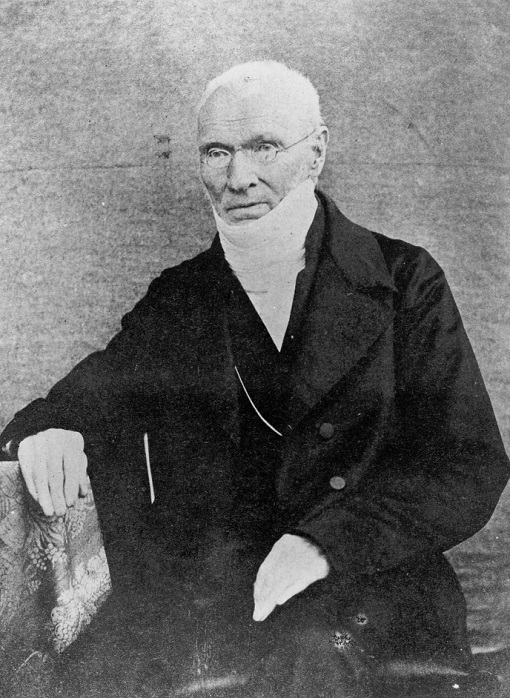

The last week in February witnessed some of the most momentous events in Reverend Patrick Brontë’s professional life. We know him, of course, as the father of Charlotte, Anne and Branwell Brontë, genius writers all and three of the six Brontë siblings. His nature could be idiosyncratic at times, and he freely admitted:

‘I do not deny that I am somewhat eccentric. If I had been numbered among the calm, sedate, concentric men of the world I should not have been as I now am. And I should in all probability never have had such children as mine have been.’

We must thank him for having the courage to bring up his children as he did, and allowing them to become the towering figures that they did. He was much more than that as well, though, so let’s take a look at three late February events that bookended his remarkable career within the Church of England.

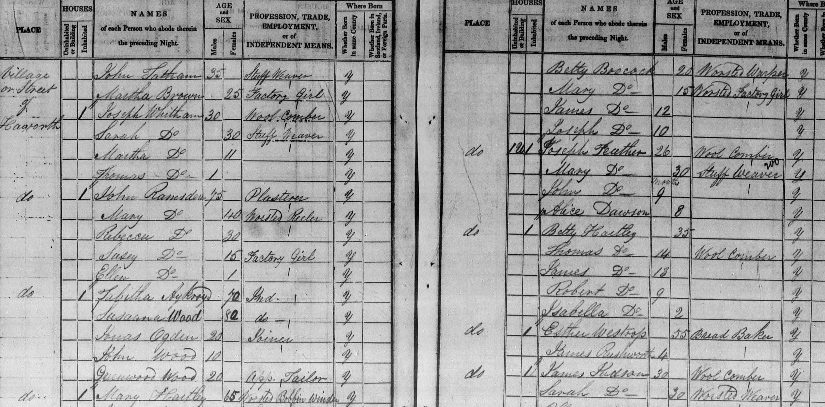

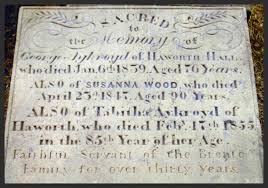

On the 25th of February 1820, little more than a month after Anne Brontë’s birth, Patrick Brontë was officially granted the perpetual curacy of Haworth, leaving behind his previous parish of Thornton. He was entering a parish made famous by a previous incumbent William Grimshaw, but also one where the villagers could be vociferous, and who weren’t afraid to stand up to their priest.

It had been a long road to Haworth for Patrick, as he had been offered the post a year earlier but declined it when locals opposed his appointment, as reported in the Leeds Intelligencer of 14th June 1819:

‘We hear that the Rev. P. Brontë, curate of Thornton, has been nominated by the vicar of Bradford, to the valuable perpetual curacy of Haworth, vacated by the death of the Rev. James Charnock; but that the inhabitants of the chapelry intend to resist the presentation, and have entered a caveat accordingly.’

It is well known now that the Haworth elders were objecting to the Vicar of Bradford appointing their priest without consulting them first, contrary to an ancient right they had. This was shown by the appalling treatment meted out to Samuel Redhead when he was appointed by Henry Heap, Bradford’s vicar, after Patrick’s retreat. Elizabeth Gaskell tells with some drama how Redhead was received, but the truth was even more incredible, as we see from a letter that the Bishop of Ripon, and later Archbishop of Canterbury, Charles Longley wrote to his wife:

‘There is an ancient feud between Bradford and Haworth… the people of Haworth can by the trust deed of the living, prevent the person appointed by the vicar [of Bradford] from entering the Parsonage or receiving any of the emoluments, if he does not please them… in the case of Mr. Redhead, the inhabitants exercised their right of resistance and opposition and to such a point did they carry it, that they actually brought a Donkey into the church while Mr. Redhead was officiating and held up its head to stare him in the face – they then laid a plan to crush him to death in the vestry, by pushing a table against him as he was taking off his surplice and hanging it up, foiled in this for some reason or other they then turned out into the Churchyard where Mr. Redhead was going to perform a funeral and were determined to throw him into the grave and bury him alive.’

Redhead managed to flee, but could obviously no longer continue in his post. A compromise was reached in which the Haworth elders would nominate a curate who would then be rubber stamped by Heap, and it was this compromise that saw Patrick appointed to the post after all in February 1820.

Patrick Brontë was entering a parish where the congregation had tried to murder the previous incumbent, how long would he endure? The answer to that is testimony to his resilience, his courage and the good standing he rapidly achieved among the people of Haworth.

The next event from this week occurred on the 22nd February 1837, when we find, once again via a report in the Leeds Intelligencer, that Patrick is chairing a meeting to protest against the introduction of the 1834 Poor Law Reform Act. This cruel act introduced workhouses in which to house those who needed benefits to survive, but the conditions inside were appalling, with husbands separated from wives, mothers from children.

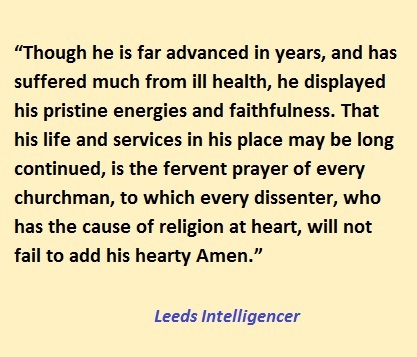

Patrick was opposed to workhouses, and he chaired what could have been a fiery meeting with aplomb, leading the newspaper report to conclude:

It is worth noting of course that whilst the reporter states that Reverend Brontë is ‘far advanced in years’, he would serve the parish for another 24 years after this date, despite the ill health alluded to (primarily his increasing blindness). The meeting was held in the school rooms that Patrick himself had had built, next to the church and the parsonage he called home. It was another of the many socially aware acts carried out in Haworth by Patrick Brontë; perhaps the greatest of all was his work in securing improvements to the water supply of Haworth. It was largely thanks to Haworth that a reservoir was built on the moors near Haworth, lavatories were installed, and that sanitation in general was greatly improved. There can be no doubts that Patrick’s tireless efforts in this cause saved thousands of lives that would otherwise have been lost to diseases such as cholera.

This last week in February also marked an end to one of Patrick Brontë’s duties as parish priest, for on this day, the 24th of February, in 1857 he carried out his final marriage service. Now approaching his 80th birthday he turned for the final time to a bride and groom and asked if they would take each other in sickness and in health. Patrick had certainly served Haworth in sickness and in health, and so it is fitting that these words he would have said hundreds upon hundreds of times throughout his decades in the parish form the title of the new exhibition in his memory at the Brontë Parsonage Museum – I look forward to visiting it next month.

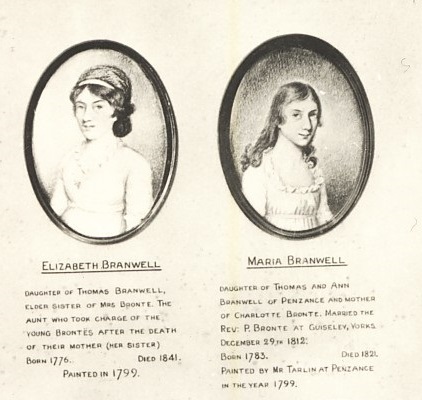

After 1857, Patrick was no longer able to carry out the daily duties demanded of a parish priest, and these were instead undertaken by Charlotte Brontë’s widow, Arthur Bell Nicholls. Nevertheless, he did from time to time take or assist in a service at the church until his well earned rest came in June 1861, meaning that he had served Haworth with distinction for more than 40 years. We know this from the last report of him, and fittingly it comes in a letter sent by his niece Eliza Kingston in Penzance, Cornwall. This letter dated March 1860 is proof of Patrick’s loyalty to the church, but also of the lifelong fidelity of his love for his wife Maria. It was nearly four decades since she had died, and yet he still cherished his memory so much that he obviously continued to write to members of her family over 400 miles away, perhaps because when doing so he felt close to her once more. I will leave you with Eliza’s words, the last words we have on Patrick Brontë, and say thank you to a great father, a great priest and a great man:

‘I had a letter from my Uncle Brontë last June. He says he was in his 83rd year, but, though feeble, was still able to preach once on Sunday, and sometimes to take occasional duty; his son-in-law, Mr. Nicholls will continue with him. He says strangers still continue to call, but he converses little with them, but keeps himself as quiet as he can. I understand the Brontës were beloved in their own neighbourhood.’

They are still beloved in all neighbourhoods.