This week 177 years ago saw the commencement of a major Brontë journey in a physical and a metaphorical sense, as on 8th February 1842 Charlotte Brontë and Emily Brontë embarked upon a voyage from Haworth to Brussels – but Anne Brontë was left behind.

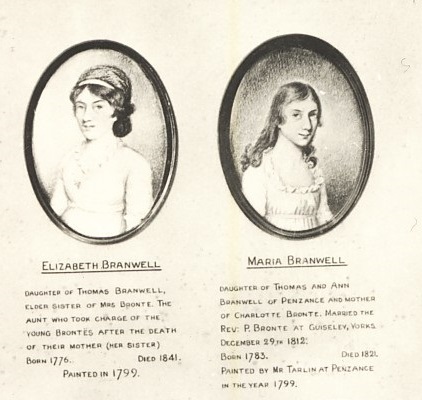

It was a journey, travelling first to London as they did, of around 430 miles – a major undertaking in the first half of the nineteenth century, although it’s easy to forget that this journey was still shorter than the one from Penzance to Haworth that their mother and Aunt Branwell had taken.

It was, in fact, Aunt Branwell that made the journey, and Charlotte and Emily’s stay in the Belgian capital, possible, but just what was it for? We gain a clue from Anne’s diary paper of 30th July 1841:

“We are thinking of setting up a school of our own but nothing definite is settled about it yet and we do not know whether we shall be able to or not – nothing is settled about it yet.”

At the time Anne wrote this she was in her second year of employment with the Robinson family of Thorp Green Hall, and Charlotte was in Rawdon serving as governess to the White family; a year earlier Emily had left her short held, but later influential, position as a teacher in Law Hill near Halifax. It seemed obvious to all three sisters that their only hope of making a living for themselves was as governesses or teachers, but they all, to a lesser or greater extent, found the demands of working in these roles difficult. It seemed obvious that they would fare better if they set up their own school and worked for each other, and by the middle of 1841 plans had begun to be made in earnest.

At this point fate seemed to be smiling on them, for Margaret Wooler, former teacher of the Brontës and employer of Charlotte, had decided to retire from teaching, and she offered Charlotte the chance to take over the running of her school in Dewsbury Moor. Heald’s House, as it was known, would have been furnished and ready to put into action, and pupils were already in place, but Charlotte was never keen on the idea, possibly because of painful memories of her own teaching days there after the school had relocated from Roe Head. By November 1841, Charlotte was writing to Ellen Nussey describing it as ‘an obscure and dreary place – not adapted for a school.’

It is clear that Charlotte had another thought developing in her mind, and she laid out her new plans in a letter sent to Aunt Branwell from Rawdon in September of that year:

“Dear Aunt, I have heard nothing of Miss Wooler yet since I wrote to her intimating that I would accept her offer. I cannot conjecture the reason of this long silence, unless some unforeseen impediment has occurred in concluding the bargain. Meantime, a plan has been suggested and approved by Mr. and Mrs. White, and others, which I now wish to impart to you. My friends recommend me, if I desire to secure permanent success, to delay commencing the school for six months longer, and by all means to contrive, by hook or by crook, to spend the intervening time in some school on the continent. They say schools in England are so numerous, competition so great, that without some such step towards attaining superiority we shall probably have a very hard struggle, and may fail in the end. They say, moreover, that the loan of £100, which you have been so kind as to offer us, will, perhaps, not all be required now, as Miss Wooler will lend us the furniture; and that, if the speculation is intended to be a good and successful one, half the sum, at least, ought to be laid out in the manner I have mentioned, thereby insuring a more speedy repayment both of interest and principal. I would not go to France or to Paris. I would go to Brussels, in Belgium. The cost of the journey there, at the dearest rate of travelling, would be £5; living is there little more than half as dear as in England, and the facilities for education are equal to or superior to, any school in Europe… These are advantages which would turn to vast account, when we actually commenced a school – and, if Emily could share them with me, only for a single half-year, we could take a footing in the world afterwards which we can never do now. I say Emily instead of Anne; for Anne might take her turn at some future period, if our school answered. I feel certain, while I am writing, that you will see the propriety of what I say; you always like to use your money to the best advantage; you are not fond of making shabby purchases; when you do confer a favour, it is often done in style; and depend upon it £50, or £100, thus laid out, would be well employed. Of course, I know no other friend in the world to whom I could apply on the subject except yourself. I feel an absolute conviction that, if this advantage were allowed to us, it would be the making of us for life. Papa will perhaps think it a wild and ambitious scheme; but who ever rose in the world without ambition? When he left Ireland to go to Cambridge University, he was as ambitious as I am now. I want us all to go on. I know we have talents, and I want them to be turned to account. I look to you, aunt, to help us. I think you will not refuse… Believe me, dear aunt, your affectionate niece, C. Brontë”

This was a masterful letter, but then again Charlotte Brontë was a consummate letter writer. Charlotte had been receiving letters from her great friends Mary and Martha Taylor who were already at school in Brussels, and her lust for travel, exploration and adventure, first evident in her juvenilia, was aflame once more. She needed a significant sum to turn this dream into a reality, but she also knew that her aunt had access to that kind of money.

The letter is also evidence of what Ellen Nussey had earlier reported, that Anne Brontë was her aunt’s favourite, and so Charlotte knew that she would have to explain why it was her aim to take Emily with her rather than Anne.

On the face of it, it might seem a strange choice – Emily’s time as a pupil at Roe Head had been a complete disaster, as she became so homesick that she was sent home within three months in fear of her life. It would not be so easy for her to return home from Brussels if the same problems recurred.

Charlotte knew however that Emily had become a different woman in the intervening seven years, and she also knew that she herself would be in need of Emily’s strength, fortitude and dependability in Belgium. Some have seen the decision as a snub to Anne, but in fact I believe Charlotte was being pragmatic and sensible. Anne had already received a longer education than either of her sisters, and she was an accomplished scholar who already knew the languages they wished to learn. Emily, on the other hand, whilst possessing a brilliant mind still had little formal education, and this could make it harder to attract pupils to a school at which she was to teach.

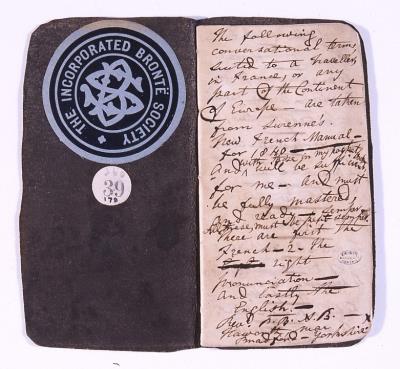

Charlotte’s letter, which carefully appealed to both her aunt and father, did the trick. She secured funding and best wishes, and thus it was that they climbed into a carriage for the first leg of their journey on that early February morning. Patrick was alongside them, for his innate sense of adventure had also been fired up, and he’d decided to accompany his daughters on their journey. He carried with him a little notebook in which he’d written phrases in English and French, along with a guide on how to pronounce them, so that one entry read: “Demain = de mang – tomorrow”

We can be sure that Aunt Branwell, and the friends and servants Tabby and Martha waved them au revoir, but Anne was only there in her mind. She was now entering a sad and lonely period, where the daily grind of a governess became ever more of a drudge. Doubtless she received letters from Brussels that must have seemed endlessly exciting when compared to the life she was compelled to live.

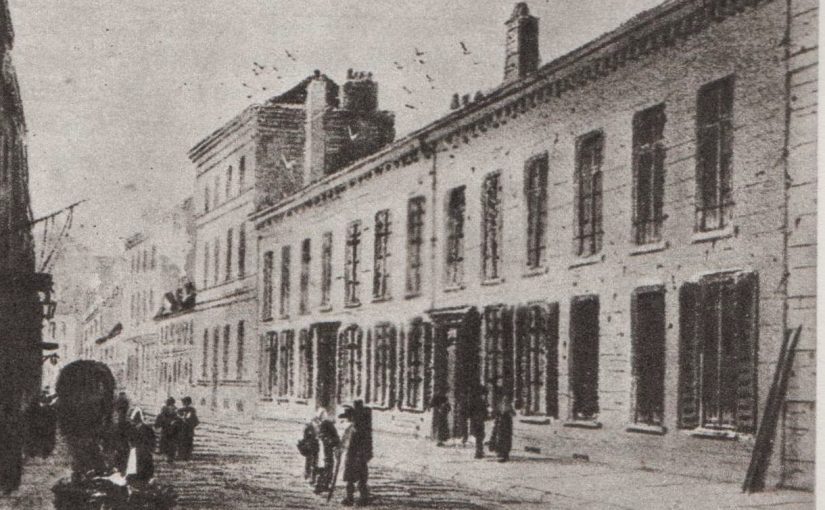

We will turn to what happened next in another post – but Charlotte finally returned from Brussels in January 1844 clutching a certificate from the Pensionnat Heger (that’s it at the top of this post) and a terrible burning unrequited love in her heart. It would haunt her for the rest of her life, it must find release – it did find release in the only way Charlotte knew how, in her writing. Thus it was that the pain of Brussels drove Charlotte on to write more than anything else, and this is why that February morning was the start of a journey that would change everything for Emily and Anne too, and for readers across the globe until the end of time.