In 1855 Charlotte Brontë Nicholls (as she termed herself) was celebrating her first Valentine’s Day as a married woman. On the 15th February she wrote to her friend Laetitia Wheelwright, saying:

“At present I am confined to my bed with illness and have been so for 3 weeks. Up to this period since my marriage I have had excellent health. My Husband and I live at home with my Father… no kinder better husband than mine it seems to me can there be in the world. I do not want now for kind companionship and the tenderest nursing in sickness… I cannot write more now for I am much reduced and very weak.”

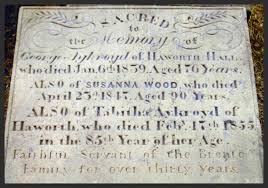

It was to be the first and last Valentine’s Day as a married woman for Charlotte, she was to find, as Anne and William Weightman had before her, that tragedy often followed close on love’s heels in that Haworth parsonage. As she blotted the letter she could not have known this, nor that death was already waiting in those familiar rooms, for just three days later, on this day in 1855, the long standing Brontë servant and friend Tabby Aykroyd died.

Tabitha Aykroyd, always known by the children as Tabby, had taken up her role as servant more than three decades earlier in late 1824, as a cost-cutting replacement for the sisters Nancy and Sarah Garrs. She would fulfil the roles of cook, cleaner, and crucially storyteller, from that day on. Little is known of her life before she entered the Haworth Parsonage, except that she was unmarried and had no children but two sisters Rose and Susanna. She was born in approximately 1771, putting her in her early fifties when she moved in with the Brontës. For many years she was the only live in servant, although in later years the younger servant Martha Brown, daughter of the sexton John, also moved in.

Patrick and Aunt Branwell would have given careful consideration to their choice of housekeeper, and so we can certainly assume that Tabby already had experience in a similar role, and she was probably well known to them as a frequenter of St. Michael and All Angels church. Patrick alluded to Tabby’s appointment in a letter to his bank on 10th November 1824:

‘I am going to send another of my little girls to school [Emily], which at the first will cost me some little – but in the end I shall not lose – as I now keep two servants but am only to keep one elderly woman now, who, when my other little girl is at school will be able to wait I think on my remaining children [Anne and Branwell] and myself’

This ‘elderly woman’ as Patrick described her, was in fact just six years older than himself. She seems to have been a forthright no-nonsense Yorkshire woman of the type still readily found today, but behind a bluff exterior she could also be very warm and loving, which is another Yorkshire trait which endures. This is confirmed by Elizabeth Gaskell, who had met Tabby:

‘She abounded in strong practical sense and shrewdness. Her words were far from flattery; but she would spare no deeds in the cause of those whom she kindly regarded.’

A strong bond formed between Tabby and the children, although we have a story of how the young Brontës delighted in frightening her on one occasion. They were acting out a play, as they liked to do, and in this particular one they must have been pretending to be demons or monsters. So good were they at this role that Tabby fled the Parsonage in terror and ran to her nephew William Wood, a coffin maker. Branwell’s friend and biographer Francis Leyland described what she said:

‘William! William! Yah mun goa up to Mr Brontë’s for aw’m sure yon chiller’s all gooin mad, and I dar’nt stop ith house ony longer wi’em; and aw’ll stay here woll yah come back!’

William went to the Parsonage and was greeted with a great cackle of laughter from the Brontë children, delighted at how successful their trick had been. This shows that Tabby was a central part of the Brontë children’s development and play time, and it also reveals the Pennine Yorkshire dialect that she and many others in the Haworth area spoke, and which Emily Brontë later put into the mouth of Wuthering Heights’ Joseph, much to the confusion of non-Yorkshire based readers ever since.

In December 1836, Tabby suffered a terrible accident which could have changed the course of her life. Haworth’s steep main street can be treacherous in winter, then and now, and Tabby slipped on ice, badly breaking her leg and leaving her with a walking impediment for the rest of her life. Aunt Branwell recommended that Tabby should be let go, not merely because she could no longer perform all her duties but so that Tabby could be looked after by her sister. The Brontë siblings, however, were having none of it. They insisted that they would look after her just as she had looked after them when they were young, and they even refused to eat until the decision was reversed, and under these circumstances Tabby was allowed to stay. It is clear that to the Brontë siblings, Tabby was an essential part of the family.

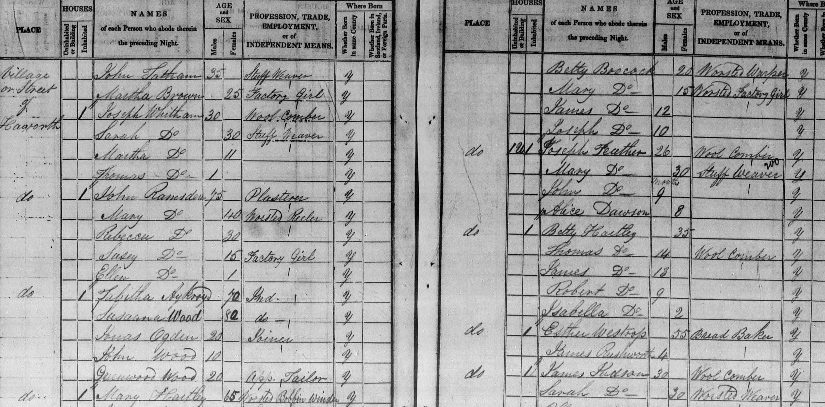

Nevertheless, Tabby’s leg injury flared up from time to time, and in 1839 she moved into the house of her sister Susanna Wood. It must have been a lengthy convalescence for she was still there when the 1841 census was taken (that’s it at the top of this page, can you find her?), but by 1842 she had returned to the parsonage. Emily Brontë had become fiercely loyal to Tabby, and she took on many of the household duties that were now a struggle for her; a far cry from Emily’s diary paper of 1834 when she had to be cajoled into helping in the kitchen:

‘Tabby said on my putting a pen into her face, “Ya pitter pottering there instead of pilling a potate”’.

Tabby of course would outlive Emily, and she and Martha provided comfort to Charlotte after the death of her sisters and brother, but a letter to Ellen Nussey of 14th September 1849 revealed a particularly distressing day for Charlotte and Tabby:

‘Both Tabby and Martha are ill in bed. Martha’s illness has been most serious, she was seized with internal inflammation ten days ago; Tabby’s lame leg has broken out – she cannot stand or walk – I have one of Martha’s sisters to help me and her mother comes up sometimes. There was one day last week when I fairly broke down for ten minutes – sat and cried like a fool. Martha’s illness was at its height, a cry from Tabby had called me into the kitchen and I had found her laid on the floor – her head under the kitchen-grate – she had fallen from her chair in attempting to rise. Papa had just been declaring that Martha was in imminent danger, I was myself depressed with head-ache and sickness – that day I hardly knew what to do or where to turn… Life is a battle May we all be enabled to fight it well.’

Martha and Tabby both recovered, and Tabby also recovered from a bout of ‘English cholera’ that Charlotte reported in 1852 (this was the less serious, less usually fatal, form of the disease). We have final news of Tabby however in a simple line from Charlotte to Ellen of 21st February 1855:

‘Write and tell me about Mrs. Hewitt’s case, how long she was ill and in what way. Papa thank God! is better. Our poor old Tabby is dead and buried. Give my truest love to Miss Wooler. May God comfort and help you.’

This letter shows both sides of life at the Parsonage. Mrs. Hewitt was a mutual friend who had suffered morning sickness when pregnant, so this line and a later letter in response to Mrs. Hewitt’s reply, is proof that Charlotte too was pregnant. And then we have a simple brief tribute to Tabby Akyroyd who had taken her final breath four days earlier. Charlotte was herself, although she didn’t know it, rapidly approaching her final day, she would have been too weak to hold the hand of the woman who had loved her so much for more than thirty years, and who had been loved back in return. Nevertheless, Tabby doubtless could feel the love around her as she left this world, and she still deserves and receives our love today.

Tabby Aykroyd brought practical and emotional support to the Brontë siblings whenever they needed it, she could always be relied upon, and it is her tales of Yorkshire folklore that helped shape the sisters’ writings. On this day, as we remember the life of Tabby Aykroyd, I can’t help but bring to mind the words from Matthew that Patrick must have read in many a sermon:

‘Well done, thou good and faithful servant!’

She played such an important role in the shaping of the Bronte family. It is easy to look at the genius of the sisters as independent of outside influence, but those who surrounded them, Tabby especially, helped to develop their genius and perhaps they wouldn’t have attained the heights that they did without them.

Great article and great reminder to appreciate Tabby!

Wow!

My Grandma said she might be was related to Tabby Ackroyd.

She wrote her story, but unfortunately burnt it, not thinking it worthy.

I feel I should start writing about her life! A true Yorkshire Women!

Thanks Wendy! What a pity the story was burnt, but what a great connection to have!