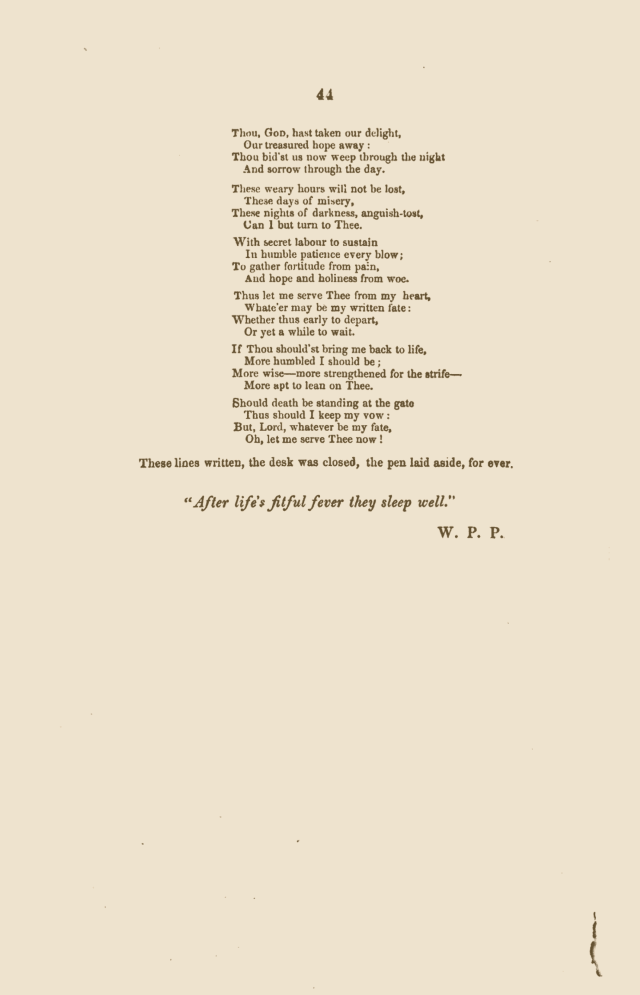

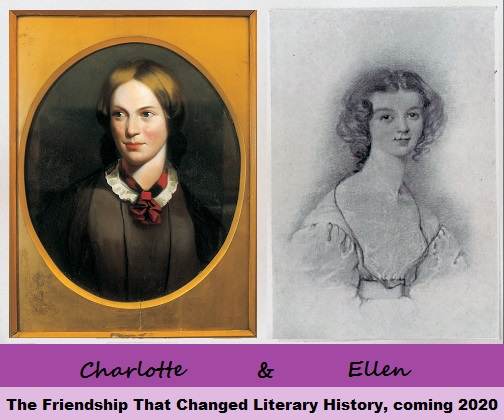

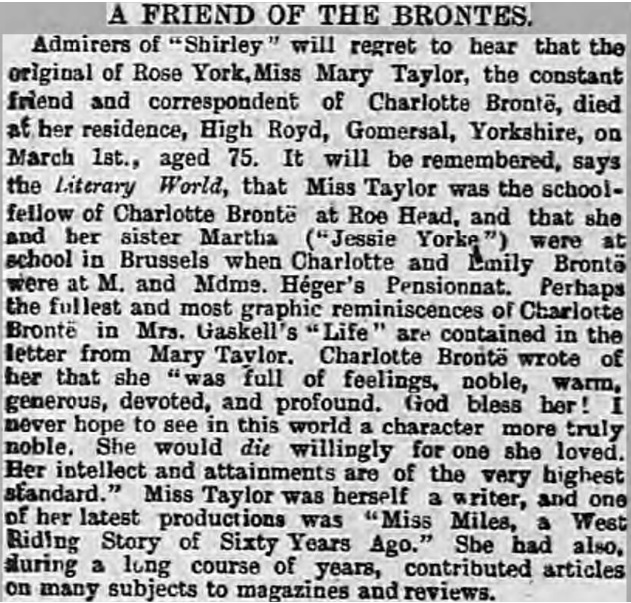

Today is a sad day for Brontë lovers worldwide, as we affectionately remember Charlotte Brontë, who died on this day in 1855 in particularly tragic circumstances – when she was looking forward to bringing a child into the world. Tragedy, of course, appears all too frequently in the Brontë story, and in the stories of some of their most celebrated fans.

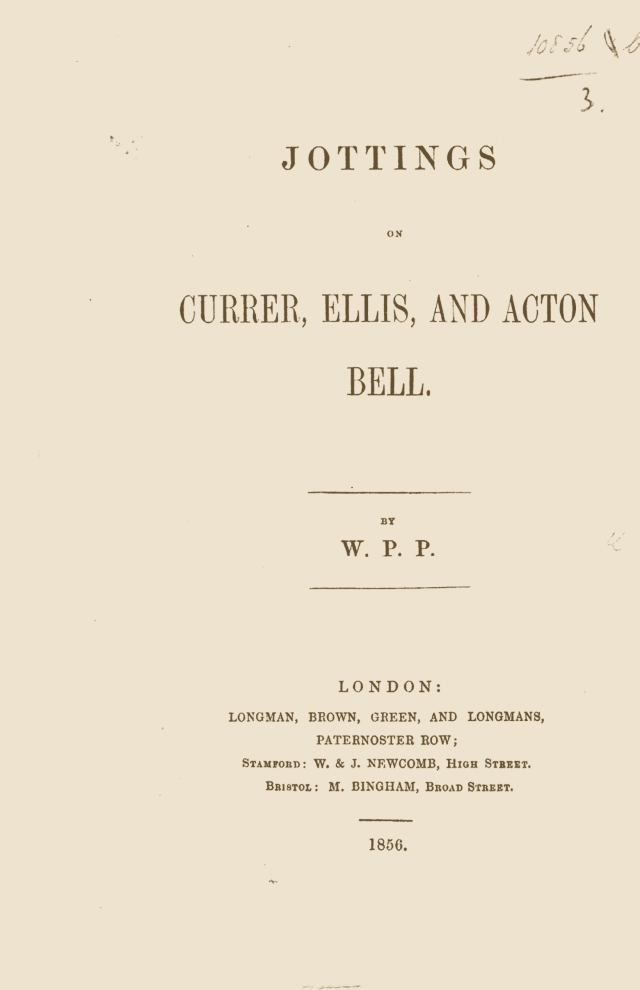

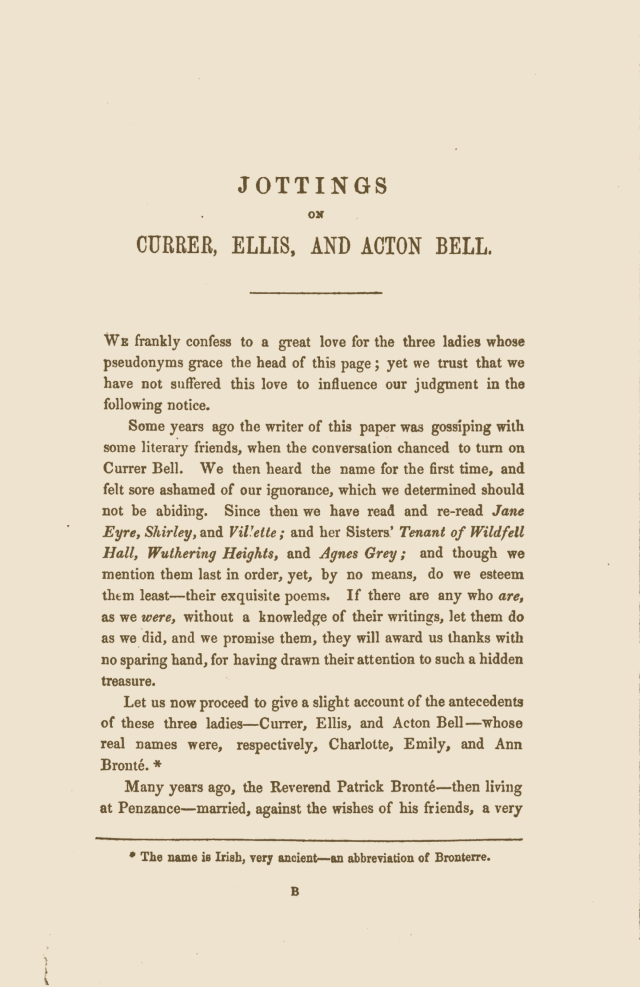

One of the sure signs of the brilliance of the writing of Anne Brontë and her sisters is that their legacy is an enduring, and still growing, one. They inspire readers across the globe to pick up their brilliant novels and poems, but throughout the years they’ve also inspired numerous writers of the very highest calibre.

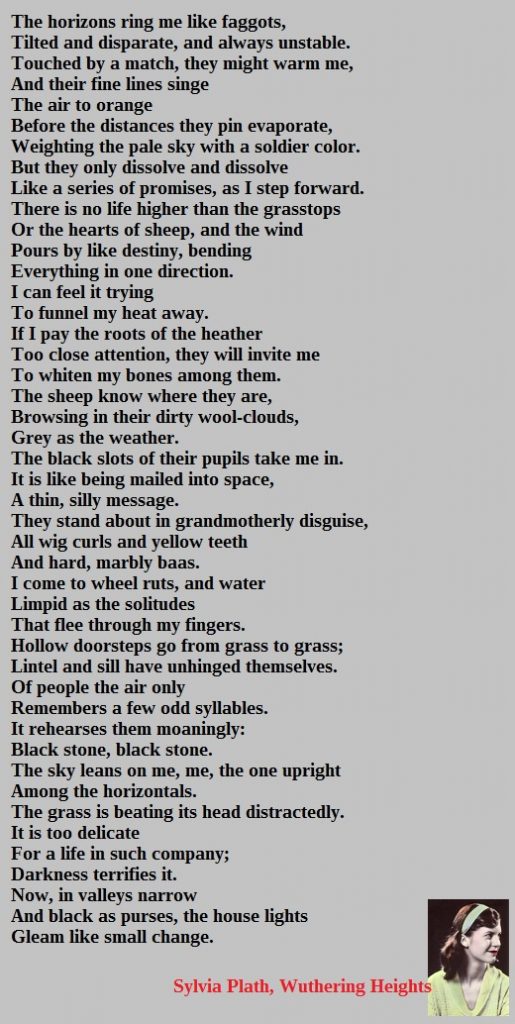

Sylvia Plath, for example, wrote a magnificent poem entitled ‘Wuthering Heights’ describing the spiritual feeling she gained from walking on Haworth’s moors. Born in Massachusetts, she is now buried in a churchyard in Heptonstall, just nine miles from Haworth.

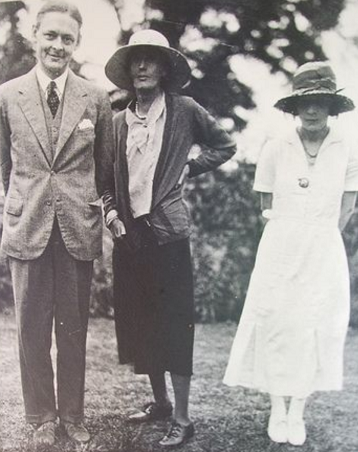

Sylvia was a giant of twentieth century poetry who left us too soon, and she shared a love of the Brontës with the woman we’re going to look at now: perhaps the greatest of all twentieth century writers, a genius who revolutionised the novel, and an equally tragic figure: Virginia Woolf.

This week marked the 78th anniversary of Virginia Woolf’s death, as she passed from this world on the 28th March, 1941. Her friend and fellow literary ground breaker T.S.Eliot, upon hearing the news, said: ‘For myself and others it is the end of the world, I feel quite numb.’

Virginia’s legacy was large and varied, but universally brilliant, and from Mrs. Ramsay of ‘To The Lighthouse’ to Clarissa Dalloway and the gender swapping, time defying, Orlando, she often takes a brilliant and powerful look at the role of women in society. Perhaps this is one thing that she took from the Brontës.

Virginia Woolf would also have been aware of the difficulties the Brontës initially had in finding a publisher, and how they had to pay to have their first books published. Virginia didn’t encounter this problem, but as she became more celebrated and more confident in her talents, she hated being censored and edited by her publishers. It was this that led her, with her husband Leonard Woolf, to found the Hogarth Press in 1917. Virginia Woolf could now publish her own books without having to see parts struck out by editors who hadn’t any of the genius that she had, but she also used it to publish works by some of the most important authors of the century, including the aforementioned Eliot, E.M. Forster and Laurens van der Post.

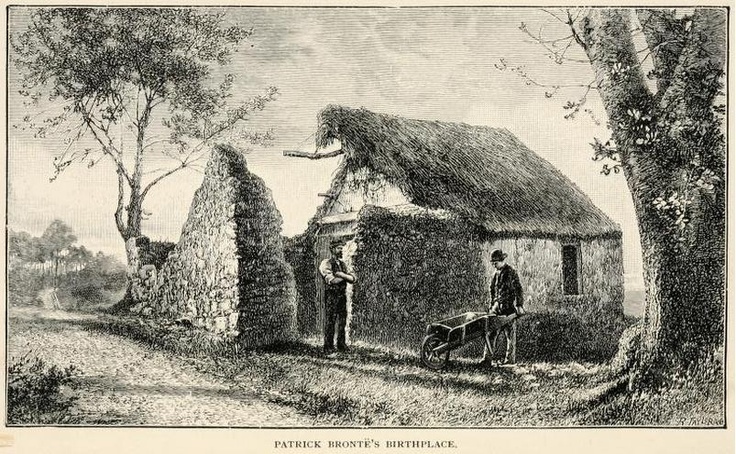

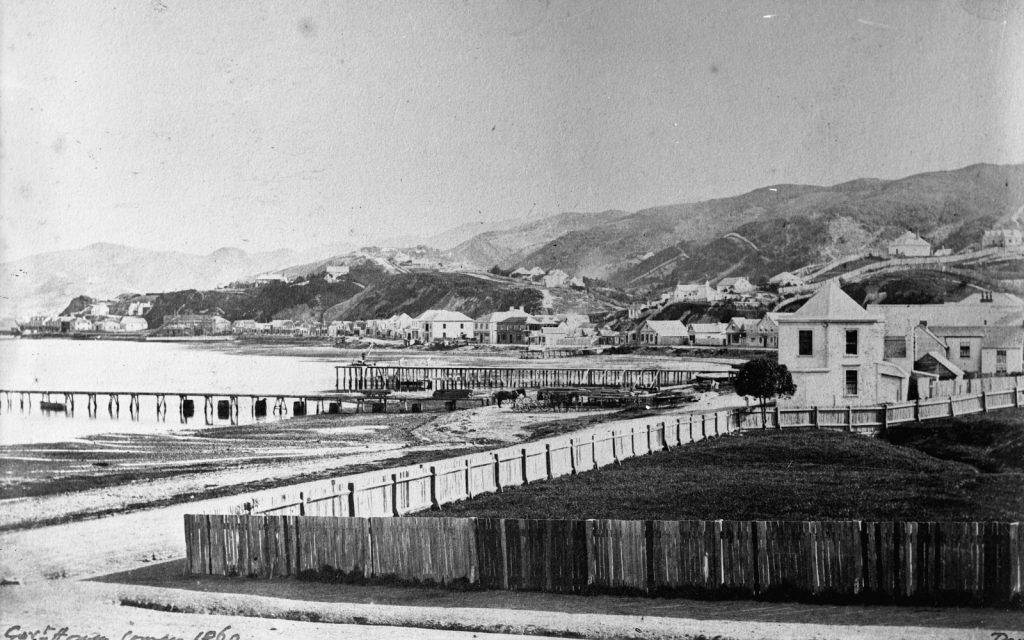

The very first work that Virginia Woolf had accepted for publication was rather different to the work she would become known throughout the world for. Published in 1904 by the Manchester Guardian it is an account of a literary pilgrimage to the home of the authors who she loved and who inspired her: the Brontës. This is an important literary moment, but an interesting historical document as well; this is before the Brontë Parsonage Museum was opened (although there was already a little museum elsewhere in the village), and we see a very different Haworth to the one we know today – a dark, grimy one much more like the one that Anne, Charlotte and Emily would have known. I leave you now with 22 year old Virginia Woolf’s brilliantly written account of her journey to Haworth, and on this day let’s remember Virginia, Sylvia and Charlotte fondly:

“I do not know whether pilgrimages to the shrines of famous men ought not to be condemned as sentimental journeys. It is better to read Carlyle in your own study chair than to visit the sound-proof room and pore over the manuscripts at Chelsea. I should be inclined to set up an examination on Frederick the Great in place of an entrance fee; only, in that case, the house would soon have to be shut up. The curiosity is only legitimate when the house of a great writer or the country in which it is set adds something to our understanding of his books. This justification you have for a pilgrimage to the home and country of Charlotte Brontë and her sisters.

The Life, by Mrs Gaskell, gives you the impression that Haworth and the Brontës are somehow inextricably mixed. Haworth expresses the Brontës; the Brontës express Haworth; they fit like a snail to its shell. How far surroundings radically affect people’s minds, it is not for me to ask: superficially, the influence is great, but it is worth asking if the famous parsonage had been placed in a London slum, the dens of Whitechapel would not have had the same result as the lonely Yorkshire moors. However, I am taking away my only excuse for visiting Haworth. Unreasonable or not, one of the chief points of a recent visit to Yorkshire was that an expedition to Haworth could be accomplished. The necessary arrangements were made, and we determined to take advantage of the first day for our expedition. A real northern snowstorm had been doing the honours of the moors. It was rash to wait fine weather, and it was also cowardly. I understand that the sun very seldom shone on the Brontë family, and if we chose a really fine day we should have to make allowance for the fact that fifty years ago there were few fine days at Haworth, and that we were, therefore, for sake of comfort, rubbing out half the shadows on the picture. However, it would be interesting to see what impression Haworth could make upon the brilliant weather of Settle. We certainly passed through a very cheerful land, which might be likened to a vast wedding cake, of which the icing was slightly undulating; the earth was bridal in its virgin snow, which helped to suggest the comparison.

Keighley – pronounced Keethly – is often mentioned in the Life; it was the big town four miles from Haworth in which Charlotte walked to make her more important purchases – her wedding gown, perhaps, and the thin little cloth boots which we examined under glass in the Brontë Museum. It is a big manufacturing town, hard and stony, and clattering with business, in the way of these Northern towns. They make small provision for the sentimental traveller, and our only occupation was to picture the slight figure of Charlotte trotting along the streets in her thin mantle, hustled into the gutter by more burly passers-by. It was the Keighley of her day, and that was some comfort. Our excitement as we neared Haworth had in it an element of suspense that was really painful, as though we were to meet some long-separated friend, who might have changed in the interval – so clear an image of Haworth had we from print and picture. At a certain point we entered the valley, up both sides of which the village climbs, and right on the hill-top, looking down over its parish, we saw the famous oblong tower of the church. This marked the shrine at which we were to do homage.

It may have been the effect of a sympathetic imagination, but I think that there were good reasons why Haworth did certainly strike one not exactly as gloomy, but, what is worse for artistic purposes, as dingy and commonplace. The houses, built of yellow-brown stone, date from the early nineteenth century. They climb the moor step by step in little detached strips, some distance apart, so that the town instead of making one compact blot on the landscape has contrived to get a whole stretch into its clutches. There is a long line of houses up the moor-side, which clusters round the church and parsonage with a little clump of trees. At the top the interest for a Brontë lover becomes suddenly intense. The church, the parsonage, the Brontë Museum, the school where Charlotte taught, and the Bull Inn where Branwell drank are all within a stone’s throw of each other. The museum is certainly rather a pallid and inanimate collection of objects. An effort ought to be made to keep things out of these mausoleums, but the choice often lies between them and destruction, so that we must be grateful for the care which has preserved much that is, under any circumstances, of deep interest. Here are many autograph letters, pencil drawings, and other documents. But the most touching case – so touching that one hardly feels reverent in one’s gaze – is that which contains the little personal relics of the dead woman. The natural fate of such things is to die before the body that wore them, and because these, trifling and transient though they are, have survived, Charlotte Brontë the woman comes to life, and one forgets the chiefly memorable fact that she was a great writer. Her shoes and her thin muslin dress have outlived her. One other object gives a thrill; the little oak stool which Emily carried with her on her solitary moorland tramps, and on which she sat, if not to write, as they say, to think what was probably better than her writing.

The church, of course, save part of the tower, is renewed since Brontë days; but that remarkable churchyard remains. The old edition of the Life had on its title-page a little print which struck the keynote of the book; it seemed to be all graves – gravestones stood ranked all round; you walked on a pavement lettered with dead names; the graves had solemnly invaded the garden of the parsonage itself, which was as a little oasis of life in the midst of the dead. This is no exaggeration of the artist’s, as we found: the stones seem to start out of the ground at you in tall, upright lines, like and army of silent soldiers. there is no hand’s breadth untenanted; indeed, the economy of space is somewhat irreverent. In old days a flagged path, which suggested the slabs of graves, led from the front door of the parsonage to the churchyard without interruption of wall or hedge; the garden was practically the graveyard too; the successors of the Brontës, however, wishing a little space between life and death, planted a hedge and several tall trees, which now cut off the parsonage garden completely. The house itself is precisely the same as it was in Charlotte’s day, save that one new wing has been added. It is easy to shut the eye to this, and then you have the square, boxlike parsonage, built of the ugly yellow-brown stone which they quarry from the moors behind, precisely as it was when Charlotte lived and died there. Inside, of course, the changes are many, though not such as to obscure the original shape of the rooms. There is nothing remarkable in a mid-Victorian parsonage, though tenanted by genius, and the only room which awakens curiosity is the kitchen, now used as an ante-room, in which the girls tramped as they conceived their work. One other spot has a certain grim interest – the oblong recess beside the staircase into which Emily drove her bulldog during the famous fight, and pinned him while she pommelled him. It is otherwise a little sparse parsonage, much like others of its kind. It was due to the courtesy of the present incumbent that we were allowed to inspect it; in his place I should often feel inclined to exorcise the three famous ghosts.

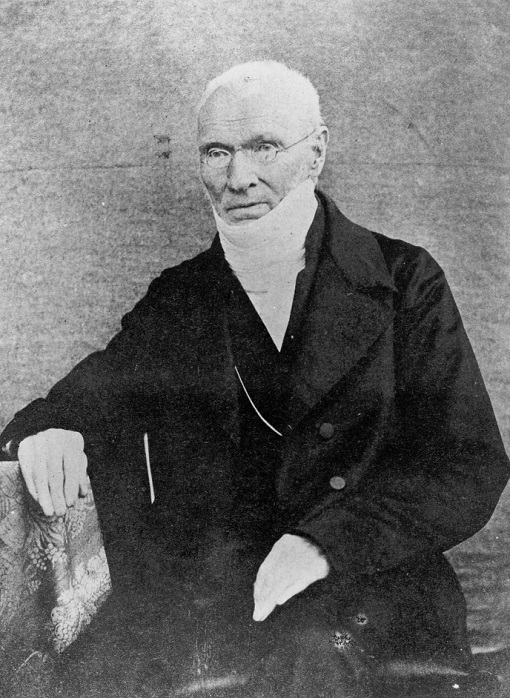

One thing only remained: the church in which Charlotte worshipped, was married, and lies buried. The circumference of her life was very narrow. Here, though much is altered, a few things remain to tell of her. The slab which bears the names of the succession of children and of their parents – their births and deaths – strikes the eye first. Name follows name; at very short intervals they died – Maria the mother, Maria the daughter, Elizabeth, Branwell, Emily, Anne, Charlotte, and lastly the old father, who outlived them all. Emily was only thirty years old, and Charlotte but nine years older. ‘The sting of death is sin, and the strength of sin is the law, but thanks be to God which giveth us the victory through our Lord Jesus Christ.’ That is the inscription which has been placed beneath their names, and with reason; for however harsh the struggle, Emily, and Charlotte above all, fought to victory.”