Anne Brontë was a lover of truth above all else, she did after all write that, ‘If I can gain the public ear at all, I would rather whisper a few wholesome truths therein than much soft nonsense.’

That’s one reason that Anne’s novels feel so vital and relevant today, she was throwing a spotlight on the society and times that she lived in, and fighting for equality and tolerance. Social justice, in its broadest sense, is something we associate more with Anne’s work than that of her sisters, and yet there is one other Brontë novel that squares up to some of the social problems of their day: ‘Shirley‘ by Charlotte Brontë.

‘Shirley’ is a long and complex novel; it’s my favourite Charlotte Brontë work, a view that the author herself shared, although I know not everyone agrees. At its heart is a love story, or two love stories to be precise, but it’s also a novel in which Charlotte looks at some of the inequalities of her time. The Luddite unrest portrayed in her novel was well known to her father Patrick who was in situ in Hartshead at the time of the attack on nearby Rawfolds Mill (that’s it at the top of this post), but Charlotte also uses the Luddite cause as a symbol of the Chartist unrest that was tangible at the time that she was writing ‘Shirley’. The north of England felt like a tinderbox, and a sudden spark could have set a working class revolution ablaze.

With political uncertainty of a different kind engulfing the UK at the moment (don’t worry, I’m steering clear of discussing that), ‘Shirley’ really is a novel for our times. I know that lots of people are reading it at this very moment, and one such reader contacted me lately with a question which we will look at in today’s post. They had visited the beautiful Hewenden Mill near Haworth; it’s now a luxurious place to stay, and they also host a number of retreats and events there, but as we shall see it was once very different.

They had been told that the mill may have connections to ‘Shirley’, and that Charlotte Brontë had once talked to the owner, a Mr Butterfield, there. That’s an intriguing suggestion which I hadn’t hear before, and although the mill and Butterfield were well known to Charlotte, it can’t be said that they were on friendly terms.

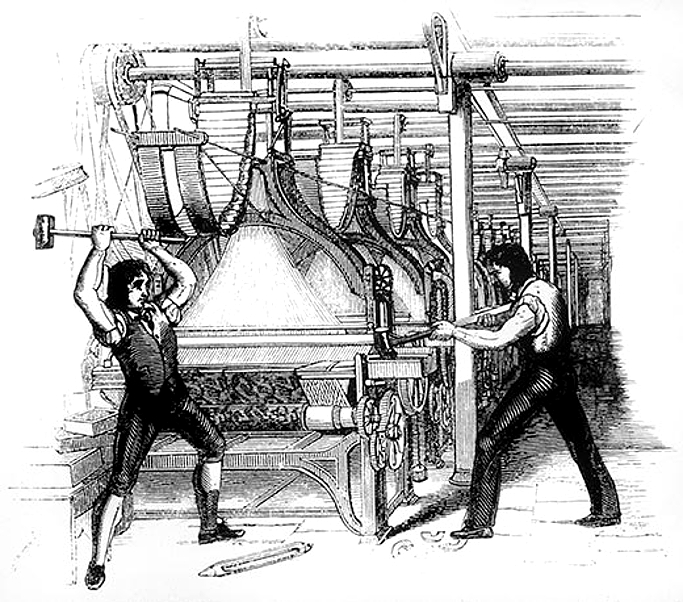

The woolen industry completely transformed the West Riding of Yorkshire, and neighbouring Lancashire, in the first half of the nineteenth century, and at the time the Brontës lived there, the population of Haworth was rapidly expanding. Many of the populace worked as hand loom weavers and spinners in infernally hot rooms within their own homes, with one property often housing multiple factories. Others, however, worked long, punishing hours at the local mills, and Hewenden Mill was among the largest.

The growing population, poor working conditions and lack of a clean water supply combined to make Haworth one of the unhealthiest places in England, comparable to Whitechapel and other inner London slums. Patrick Brontë realised this, and it was his persistent lobbying that led the government to send an official inspector to Haworth, Benjamin Herschel Babbage, in October 1849. The findings were shocking, something had to change. Nevertheless, Patrick still had to lobby for the recommended changes to be implemented, including better sanitation and the building of a reservoir on the moors outside the village.

This saved thousands of lives over the years and decades to come, but one man in particular opposed Patrick’s philanthropy: the mill owner Richard Shackleton Butterfield. Butterfield was, in short, almost a caricature of a wicked Victorian industrialist. Immensely wealthy, he paid his workers the lowest wage possible, and vehemently opposed any moves to improve the quality of life of mill workers. His mill was staffed by the bare minimum number of workers, which he achieved by making them work two looms each at a time, a very dangerous practise.

On 18th May 1852 his workers downed tools and went on strike. When they refused to return, Butterfield, who was also a magistrate, had eight ringleaders arrested, and two were sentenced to do two months’ hard labour. A third man, Robert Redman declared in court that he had evidence which would prove Butterfield’s malpractice and law breaking. We don’t know the nature of this evidence, but it was enough to make the mill owner throw up his hands and admit that he was at fault. The men were freed, and Butterfield was ordered by the court to pay the mens’ wages.

Many in Haworth delighted at this defeat for the unpopular mill owner, and we know that Patrick, who’d had many a run in with him, and his daughter Charlotte were among them. On 2nd June 1853, Charlotte Brontë wrote to her father from Filey, stating:

‘I cannot help enjoying Mr. Butterfield’s defeat – and yet in one sense this is a bad state of things, calculated to make working class people both discontented and insubordinate’

Charlotte was clearly conflicted. Earlier posts have shown how Charlotte herself had become known around the Haworth area for her philanthropy and her kindness towards the poor, and yet at heart she was also a believer in many of the social systems that were in place at the time. This conflict of the author is also evident in ‘Shirley’, are we supposed to side with Moore the mill owner, who is the romantic hero after all, or his downtrodden workers?

One thing seems clear to me, if Charlotte Brontë had indeed walked and talked with Richard Butterfield, it would only have been to mediate in some sort of dispute between him and her father. Both Richard Butterfield and Patrick Brontë were among the most influential and powerful men in the Haworth district at the time, but there the similarity ended.