November 5th is bonfire night, although many places now choose to hold bonfires and loose their fireworks the weekend before, so the chances are that you’ve already experienced the ear shattering screams of a thousand sky rockets over the last day or two. It’s an experience loved by children especially, and it must also have been well known to the Brontës as Haworth would have held its own bonfire on an annual basis.

We can be sure of this because, until it was finally repealed in 1859, every parish in England was beholden to comply with the Observation of 5th November 1605 Act. This act was made law in the immediate aftermath of the foiling of the gunpowder plot, and it made the lighting of bonfires compulsory to commemorate the failure of the plot, and act as a reminder to people of how close the plot had come to succeed. The country was bitterly divided along religious times at the beginning of the seventeenth century, and the message behind the mandated bonfires was clear – be alert for people who are enemies of the state, and if you are one of the enemies, watch out lest you too end up on an earthly fire or in an eternal one.

The day to day violence on religious lines had long since ended by the nineteenth century, although anti-Catholic sentiment, and anti-Irish sentiment, still ran deep and this may be one of the factors behind Patrick changing the family name to Brontë from the more Irish sounding Brunty or Prunty. As his church and parsonage were at the high point of the village it would have made sense for the parish bonfire to be held nearby, and at the very least Patrick would have been expected to make an appearance at the event.

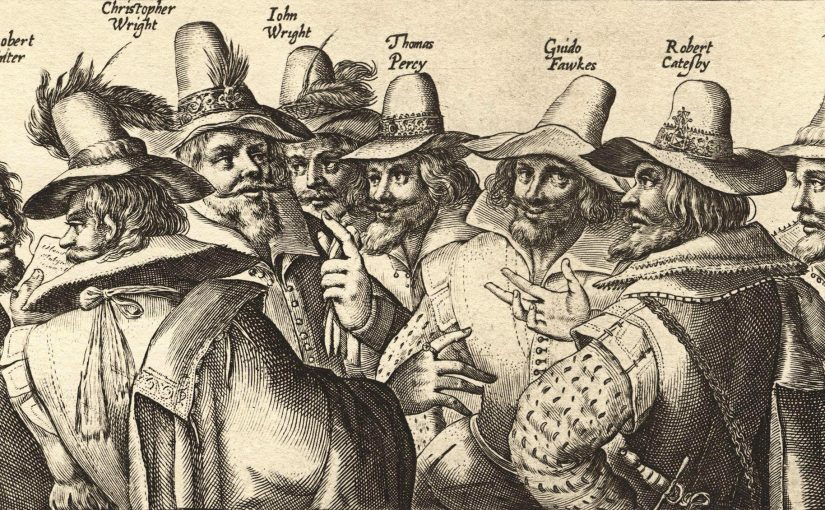

It leaves us wondering what the Brontës would have felt of bonfire night, and of Guy Fawkes? As the author of a book on Guy I’m often asked about him at this time of year, and it’s fair to say that perceptions of him have changed greatly since he was captured in the early hours of the 5th of November 1605, just hours before he lit the fuse which would have blown parliament, and the whole Westminster area, to smithereens, changing the course of history in the process.

He rapidly became the face of evil personified, with the Bishop of Rochester famously denouncing Guy from his pulpit as ‘the devil from the crypt’, and the word Guy quickly became synonymous with a wicked person, as in ‘he’s a complete guy!’. Over the centuries it has lost its pejorative meaning, but the use of guy as a generic term for man or person originates in the infamy attached to Guy Fawkes. Today, many see Guy as a hero and his face is among the most instantly recognisable in the world thanks to its use in the ‘V For Vendetta’ cartoons and film, and its adoption as a mask that can be found in protests across the globe.

As today, by the nineteenth century fireworks too had become synonymous with bonfire night, and we can imagine the young Brontës looking up as they exploded into the sky above Haworth’s moors. The most popular fireworks at the time were squibs and a piece known as the ‘firing pistol’, presumably because it made a cracking sound. They weren’t as spectacular as today’s fireworks but they were far more dangerous, and newspapers across the country in early November would be filled with tragic tales of adults and children maimed, or worse.

On 15th November 1838, for example, we can read of James Taylor, aged 17. He had been attending a bonfire at Mold Green near Huddersfield, and, the Bradford Observer reported, his pockets were filled with four dozen squibs and two ounces of gunpowder. A spark from the bonfire found its way into a trouser pocket, with predictably dire results.

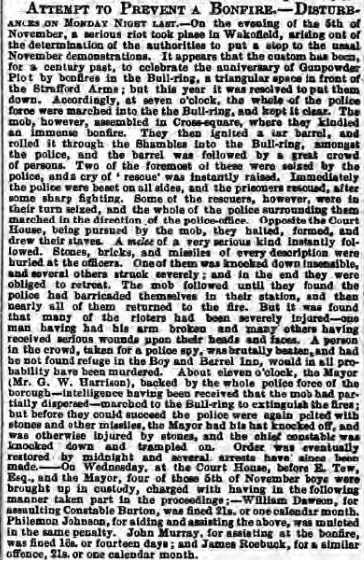

Contemporary reports also reveal that bonfires could be a tinder box in more than one way. By the first half of the nineteenth century many people were already seeing Guy Fawkes as an example of righteous rebellion, and rallying to his cause, meaning that bonfires could be riotous affairs. Mindful of this, authorities in Wakefield, a city in the West Riding of Yorkshire, attempted to ban the bonfire of 5th November 1849. As this report in the Leeds Intelligencer reveals, a riot erupted in which police were attacked, prisoners freed, a bystander accused of being a police spy was nearly murdered, oh and the Mayor of Wakefield had his hat knocked off:

We know that Patrick Brontë was terrified of fire, and for that reason wouldn’t allow curtains in the parsonage. He probably wasn’t too enthused about riots either, so it could be that his children were left to watch the bonfire and fireworks through the safety of a parsonage window. Nevertheless, we know that the Brontës must have been interested in, or at least aware of, the story of Guy Fawkes as Charlotte Brontë refers to him in ‘Jane Eyre‘, as the young Jane recovers from her red room ordeal:

‘Bessie invited him to walk into the breakfast-room, and led the way out. In the interview which followed between him and Mrs. Reed, I presume, from after-occurrences, that the apothecary ventured to recommend my being sent to school; and the recommendation was no doubt readily enough adopted; for as Abbot said, in discussing the subject with Bessie when both sat sewing in the nursery one night, after I was in bed, and, as they thought, asleep, “Missis was, she dared say, glad enough to get rid of such a tiresome, ill-conditioned child, who always looked as if she were watching everybody, and scheming plots underhand.” Abbot, I think, gave me credit for being a sort of infantine Guy Fawkes.’

Whatever you do this bonfire night, have fun and stay safe (and of course keep your pets indoors, safe and sound). Guy was captured just after midnight on the 5th of November and by a coincidence at that exact same time this year I will be talking about him on Radio 2, so if you’re still up and need something to send you to sleep, do tune in.