- As we all know, the Brontë siblings missed out on many of the familial connections that most people today take for granted. Their mother died when they were all in infancy, with Anne Brontë just one year old, and although they had lots of aunts and uncles on both sides of the family the distance between Yorkshire and their homelands of Ireland and Cornwall precluded them visiting their nieces and nephew. The exception to this being Aunt Branwell of course, who started a new life in Yorkshire to look after her sister’s children.

What is quite certain is that the Brontës knew none of their grandparents, and never knew the unique love that can form between those generations. I was lucky enough to live with my grandmother Ivy between the ages of 8 to 15, and I have her to thank for everything good in my character. Not a day goes by when I don’t think of her, and I often dream of her too – and that set me wondering whether the Brontës heard tales of their grandmothers or asked questions about them, and if so, what would they have heard?

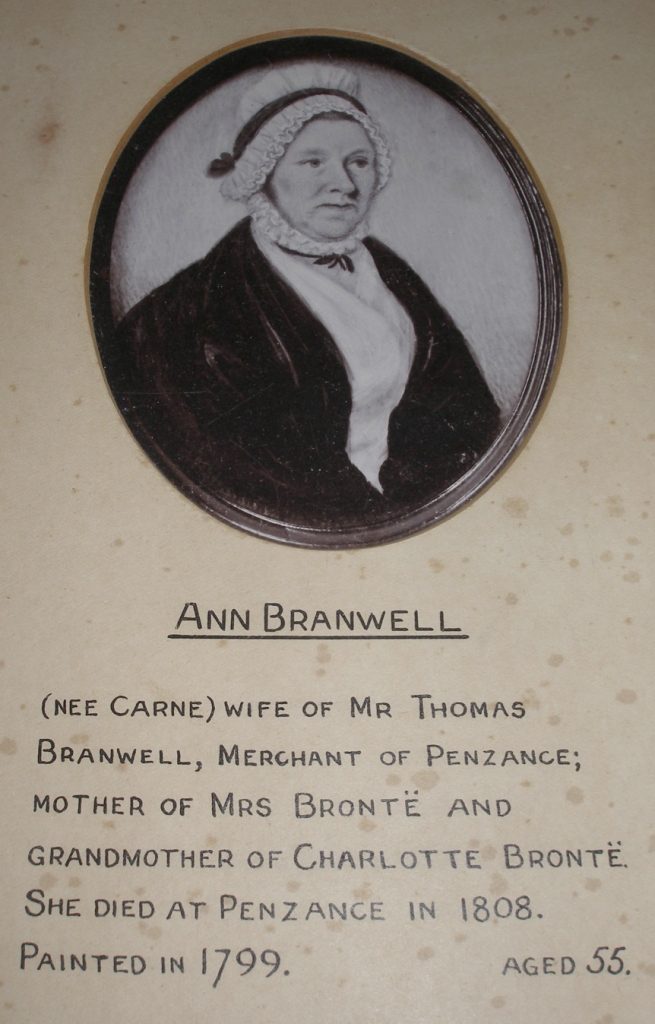

Anne Carne was the maternal grandmother of the Brontës. She was born in Penzance, Cornwall, in 1744, the daughter of John Carne and his wife Anne (nee Reynolds). The Carnes were a leading family in Penzance society, firstly for their success as merchants and then for their role in setting up the first bank in the town – Batten, Carne & Carne, which opened its doors in 1797.

The Carnes were also among the early Wesleyans in this town that became such a stronghold of the emerging faith which came to be known as Methodism. The Wesleys, John and his brother Charles who became famous for his hymns, brought a new evangelicalism to the Church of England, preaching the importance of temperance but also the reality of a loving and forgiving God. They were also heavily in support of better working and living conditions for the poorest in society, which brought them great popularity in places like Cornwall.

John Wesley travelled the country, preaching outdoors to huge crowds, but at first Penzance’s minister John Borlase was less than happy to see him and threatened to have him put in jail if he visited the region again. By 1860 Wesley was writing that: ‘at Noon I preached on the cliff near Penzance, where no one now gives an uncivil word.’

Surely among the large crowd on this occasion was Anne Carne and her family, and also another prominent merchant family of Penzance who were firm advocates of Wesleyanism: the Branwells. It may have been this shared piety that brought Anne Carne and Thomas Branwell together, but it was also certainly a good match on financial terms, uniting as it did two of Penzance’s wealthiest families. They married on 28th November 1768 in Madron parish church.

We might also like to think that, not always the case with such weddings, this was a love match. Anne and Thomas had a very productive marriage, having twelve children, not all of whom survived infancy. Anne gave birth to her final child, her daughter Charlotte, in 1789, when she was 45 years of age. It was Anne’s eleventh child, Maria, who left Cornwall for Yorkshire and became the mother of the Brontë siblings.

Thomas Branwell died in April 1808, and Anne followed him to the grave just a year later – the grief over the loss of her husband possibly hastening her own end. Anne Branwell, nee Carne, was obviously a woman of some character keeping such a large family in check – and from what we know of her daughters Elizabeth and Maria it seems that she encouraged education and independence in her children, sons and daughters alike. Maria never forget her mother’s influence, and paid tribute to her by naming her fifth daughter after her: Anne Brontë.

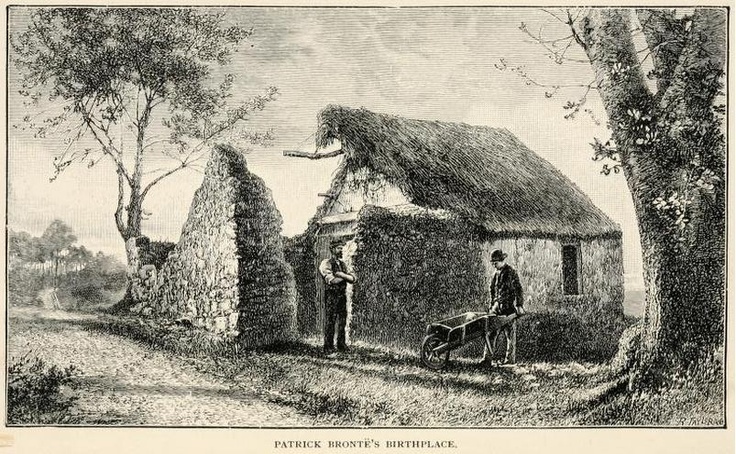

The Brontës’ paternal grandmother was Alice McClory (some accounts give her name as Ayles McClory or Eleanor McClory) of Ballynaskeagh, County Down, and her son Patrick Brontë remembered her thus in a letter to Elizabeth Gaskell: ‘He [Patrick’s father Hugh] was left an orphan at an early age. It was said that he was of ancient family… He came to the north of Ireland and made an early but suitable marriage. His pecuniary means were small – but renting a few acres of land, he and my mother by dint of application and industry managed to bring up a family of ten children in a respectable manner.’

We can be sure that Alice’s marriage to Hugh was indeed a love match, for they crossed a divide that was hugely important in Ireland at the time (and still is now, to a lesser extent): whilst Hugh was a Protestant, Alice was a Catholic.

A 19th century book by William Wright called ‘The Brontës In Ireland’ attempted to trace these roots. Doubt has been raised over some of the statements in the book, but he gives us a rather lovely account of the Brontë grandmother Alice:

‘On Christmas Eve Hugh Brontë drove up furiously in a Newry gig to the house of McClory in Ballynaskeagh. He was becoming a somewhat vain man, and fond of admiration; and no doubt, as he approached McClory’s thatched cottage, with his pockets full of money, and with the self-confidence which prosperity breeds, he meant to flutter the house with his magnificence. But a surprise was in store for him. The cottage door was opened in response to his somewhat boisterous knock by a young woman of dazzling beauty. Hugh Brontë, previous to his flight, had seen few women except his aunt Mary, and in the days of his freedom he had become acquainted only with lodging-house keepers, and County Louth women, who carried their fowls and eggs to Dundalk fairs and markets. He had scarcely ever seen a comely girl, and never in his life any one who had any attractions for him.

The simply dressed, artless girl who opened the door was probably the prettiest girl in County Down at the time. On this point there is absolute unanimity in all the statements that have reached me. The words “Irish beauty and pure Celt ” have often been used in describing her. Her hair, which hung in a profusion of ringlets round her shoulders, was luminous gold. Her fore-head was Parian marble. Her evenly set teeth were lustrous pearls, and the roses of health glowed on her cheeks. She had the long dark- brown eyelashes that in Ireland so often accompany golden hair, and her deep hazel eyes had the violet tint and melting expression which in a diluted form descended to her granddaughters, and made the plain and irregular features of the Brontë girls really attractive. The eyes also contained the lambent fire that Mrs. Gaskell noticed in Charlotte’s eyes, ready to flash indignation and scorn. She had a tall and stately figure, with head well poised above a graceful neck and well-formed bust; but she did not communicate these graces of form to her granddaughters. There are people still living who remember the stately old woman “Ayles” Brontë, as she was called by her neighbours in her old age.

Hugh Brontë was completely unmanned by the radiant beauty of the simple country girl who appeared before him. He stood awkwardly staring at her with his mouth open, fumbling with his hat, and trying in vain to say something. At last he stammered out a question about Mr. McClory, and the girl, who was Alice McClory, told him that her brother would soon be home, and invited him into the house.’

Hugh fell instantly in love with the ‘Celtic beauty’ Alice, and it is believed that they eloped and married clandestinely, with the help of a complicit vicar prepared to ignore the different faiths, in Magherally church. The cottage that Alice and Hugh lived in in Emdale still stands, and remains a site of Brontë pilgrimage today.

We have Patrick’s own words as testimony to what a remarkable and forceful woman Alice was. She was a woman who worked hard and would do anything for her children. She had that in common with Anne Carne, and the strength of their genes surely passed down into their grandchildren.

Today we say thank you to Anne Carne and Alice McClory and to grandmothers across the world, many of you reading this, I know, will have grandchildren of your own – keep on doing an amazing job and giving the unconditional love that comes with that role. Let’s remember our own wonderful grandmothers today as well, whether they are still with us or not for once somebody touches your heart they’re always with you.