This festive period should be a happy time, a chance to spend quality time with those you love, eat too much, drink too much, and watch too many Poirot movies (can you ever watch too many Poirot movies?). I hope you’ve all had a jolly Christmas and are looking forward to a happy and productive 2020. Six people were certainly having a happy, if perhaps a little nerve-jangling, time on this day in 1812. They are at two separate locations exactly 400 miles apart, but they have a timeless connection. What could it be? Let’s take a look at these six individuals, put our little grey cells to use, and then read an account that reveals the truth about the extraordinary events.

Let us begin in Guiseley, where standing nervously in the cold air outside St. Oswald’s Church is William Morgan. It is a cold Tuesday morning, and perhaps Morgan is waiting to greet his congregation for a week day service, for he is a minister in the Church of England. This, however, is not his church, and he is far from his Welsh homeland. Morgan was at the time a 30 year old curate in the diocese of Bierley near Bradford, whereas Guiseley was a larger parish situated between Bradford and Leeds.

Perhaps Morgan’s eyes sparkle as he thinks of a woman who is making her way to St. Oswald’s at this very moment, one who he first met three years earlier in Shropshire and whom fate brought into his path again here in the West Riding of Yorkshire? Jane Fennell is her name; she is 21 years old, and has travelled extensively throughout her young life, although she still bears traces of her original Cornish accent. The reason for her peripatetic life up to this point is that her parents are ardent followers of Wesleyanism, what we now know as Methodism. Following the examples of its founder John Wesley they have travelled to spread his message of love and salvation for all, and after a sojourn in the town of Wellington in Shropshire, they have formed a Wesleyan School at Woodhouse Grove in Apperley Bridge, five miles from Bradford and eight from Leeds. Jane’s father John Fennell is also here in Guiseley, glancing often towards Morgan, a man whom he has recently employed in his school.

Jane’s mother is here too, another Jane Fennell although her maiden name was Jane Branwell. She will be casting appreciative, if teary, eyes not only at her daughter but at her niece who will arrive at the church with Jane – Maria Branwell, who left Cornwall just half a year earlier. The Fennells had made Maria an offer of employment at their new school in Yorkshire. Jane Fennell senior had been sister to Maria’s father Thomas. Following the death of Thomas Branwell in 1809, Jane knew that her niece Maria was looking for a new start, and a chance to make her own way in life. She also knew of Maria’s intelligence and practical nature, so it seemed a good move for all to invite her to help in the running of the school. Perhaps Maria is in Guiseley today as bridesmaid to her cousin Jane Fennell, for when Jane arrives we can see that she is attired in a bride’s white ensemble? Maria , too, is all in white.

Maria Branwell’s glance turns sideways to another man waiting by the altar of St. Oswald’s Church. He is an Irishman in his 36th year, and he too is a new arrival in this area of Yorkshire. Patrick Brontë is curate at St. Peter’s Church in Hartshead-cum-Clifton, but in the summer he had also accepted the post of Classics examiner at Woodhouse Grove School. Patrick had met the head of the school John Fennell during a stint as curate in Wellington, Shropshire in 1809. It was in Wellington also that he had first met William Morgan, also a Shropshire curate at the time. Three men who met in Shropshire in 1809 now standing in a church in Yorkshire three years later. Patrick began his duties at Woodhouse Grove just as John Fennell’s niece Maria arrived from Cornwall. Fate will always work her magic, but sometimes she has fun adding a few twists and turns along the way.

It is to Cornwall that our gaze turns now, and we see a very different church – St. Maddern’s at Madron, the official parish church of the growing town of Penzance. Standing outside the church is a 35 year old woman dressed in fine silk, as she loved to do – she was always one for the fun and gaieties of her native town. Her name is Elizabeth Branwell, she is the eldest surviving sister of Maria who at that same moment walks down the aisle in Guiseley, 400 miles to the north. Elizabeth is happy on this day, she likes to organise things, and through a series of letters relayed from south to north and from north to south, she has helped to bring off a rather unique, and uniquely happy, event. The Branwells are a leading merchant and political family in this southwestern tip of England, and the crowd of people gathered outside shows that a marriage is to take place. Elizabeth is not the bride – she will never play that role, although her name is found time and time again as witness to the marriages of her siblings. Perhaps her love had died many years ago in the icy waters of Scandinavia? There will be nobody else for Elizabeth, but today, as always, she will be there for her family, and it is her youngest sister that she is now acting as bridesmaid for.

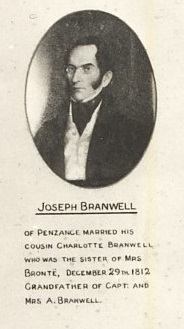

Elizabeth has long been familiar with the man who is the centre of attention on this day, for he is her cousin Joseph Branwell. Originally a teacher, he has recently changed course and commenced a career as a banker at Bolitho’s Bank. He is a man with seemingly a sound future ahead of him, and he has eyes only for the blonde haired woman, all in white, by his side – his cousin Charlotte.

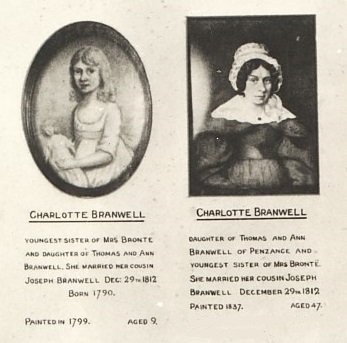

20 year old Charlotte Branwell is the youngest of the Branwell family, the last of twelve children born to Thomas Branwell and Anne Carne. She and Joseph will go on to have ten children of their own; they are deeply in love. Charlotte’s thoughts on this day are on her husband, of course, and on her family alongside her, but also on that church in Guiseley that first caught our attention.

So, there we have a cast of characters who, despite a separation of 400 miles, all seem to be connected to each other. As the wedding bells ring out in Yorkshire and Cornwall, and six names complete the registers of marriage, it makes me think of Poirot’s pronouncement as the denouement of the seemingly impossibly convoluted ‘Murder On The Orient Express’ approaches:

“I said to myself: This is extraordinary – they cannot all be in it! And then, Messieurs, I saw light. They were all in it. For so many people connected with the Armstrong case to be travelling by the same train through coincidence was not only unlikely: it was impossible. It must be not chance, but design.

We see the same in the Brontë and Branwell case playing out on this day exactly 207 years ago today. Three loving couples have married each other: William Morgan and Jane Fennell, Joseph Branwell and Charlotte Branwell, and, of most interest to us, Patrick Brontë and Maria Branwell. They have married each other at the same time, despite the distances between them, not by chance, but by design. We have proof of this in a letter published by The Cornish Telegraph on Christmas Day 1884. It was written, just to make things even clearer, by another Charlotte Branwell – the by then 59 year old daughter of Charlotte and Joseph who we encountered above. A triple wedding at Christmas – what a delightful thing, and perfect festive fare for us all to think about today. I leave you with the letter now, and wish you all a happy end to 2019 – I will see you in the New Year:

“It was arranged that the two marriages [Patrick and Maria and William and Jane] should be solemnized on the same day as that of Miss Charlotte Branwell’s mother, fixed for 29th December in far off Penzance. And so, whilst the youngest sister of Mrs. Brontë was being married to her cousin, the late Mr Joseph Branwell, the double marriage, as already noted was taking place in Yorkshire. Miss Charlotte Branwell also adds that at Guiseley not only did the Rev. Mr Brontë and the Rev. Mr Morgan perform the marriage ceremony for one another, but the brides acted as bridesmaids for each other. Mr Fennell, who was a clergyman of the Church of England, would have united the young people, but he had to give both brides away. Miss Branwell notes these facts to prove that the arrangement for the three marriages on the same day was no caprice or eccentricity on the part of Mr Brontë, but was made entirely by the brides. She has many a time heard her mother speak of the circumstances. ‘It is but seldom,’ continues Miss Branwell, ‘that two sisters and four cousins are united in holy matrimony on the same day.’”

What a confluence of events! That must have been a truly happy day for all involved, as they began their lives together. And fortunate for us that we can tag along as avid readers.

I’m descended from Charlotte Branwell who married her cousin Joseph Branwell. 🙂

How wonderful! I’d love to hear more.