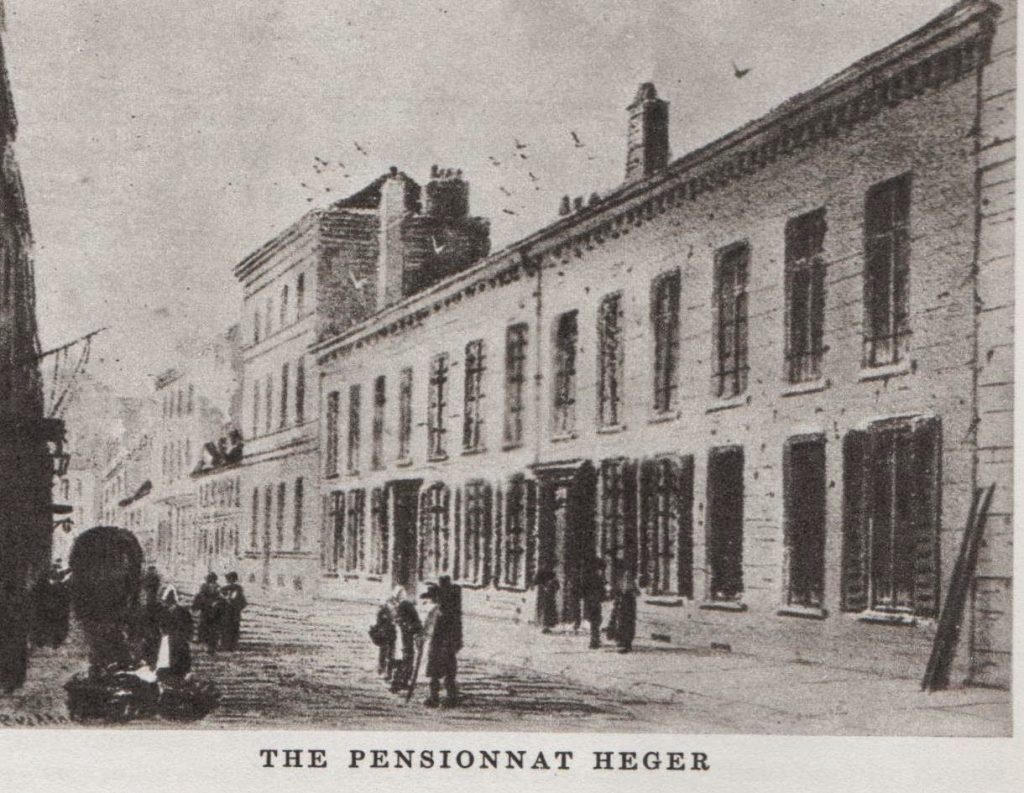

On this day in 1842 two British girls were settling down to a life that was completely alien to the one they had known. They were four hundred miles from home, in a country where the language was alien to them and the Catholic atmosphere just as foreign. They were of course Charlotte Brontë and Emily Brontë, who arrived at the Pensionnat Heger school in Brussels on 15th February 178 years ago. Today we’ll look at how this Belgian adventure affected Charlotte, Emily and Anne.

Let’s begin, appropriately for this blog and especially in this year, with Anne. Of course, Anne never made it to Brussels, indeed never travelled outside of England, but why did Charlotte choose Emily to accompany her to Belgium and not her youngest sister? On one hand, Anne would have seemed a more obvious choice for two reasons: Emily had lasted only a brief time at her previous school, Roe Head, before she was sent home suffering from such severe home sickness that Charlotte was worried she would die – it would not be so easy to return from Brussels as it had been from Mirfield should the same symptoms recur. Secondly, Emily was proving of huge value in Haworth Parsonage because of her domestic skills.

A clue to Charlotte’s choice comes in a letter that she sent to Aunt Branwell in August 1841 (from Rawdon where she was then a governess) in an effort to secure the funds she and Emily would need:

‘Dear Aunt… my friends recommend me, if I desire to secure permanent success, to delay commencing the school for six months longer, and by all means to contrive, by hook or by crook, to spend the intervening time in some school on the continent. They say schools in England are so numerous, competition so great, that without some such step towards attaining superiority we shall probably have a very hard struggle, and may fail in the end. They say, moreover, that the loan of £100, which you have been so kind as to offer us, will, perhaps, not all be required now, as Miss Wooler will lend us the furniture; and that, if the speculation is intended to be a good and successful one, half the sum, at least, ought to be laid out in the manner I have mentioned… These are advantages which would turn to vast account, when we actually commenced a school – and, if Emily could share them with me, only for a single half-year, we could take a footing in the world afterwards which we can never do now. I say Emily instead of Anne; for Anne might take her turn at some future period, if our school answered.’

Of course we know that in the end the school did not answer, but the generous aunt did, and she provided the money that allowed Charlotte and Emily to leave for the continent. Anne was always Aunt Branwell’s favourite niece, as attested to by Ellen Nussey, so Charlotte was careful to explain the possibility that Anne could also travel to Belgium at a later date. I believe that this was indeed Charlotte’s plan, rather than being in any way a snub to Anne. Anne Brontë was at that time a governess at Thorp Green Hall near York, and highly valued in her job, so it would have seemed more expedient to let Anne continue to hone these skills, and earn her salary, and take Emily to Brussels instead. Nevertheless, we can imagine Anne’s heart sinking as she thought of her sisters starting their continental adventure whilst she remained in a daily routine which she found a drudgery.

Charlotte’s years in Belgium (she spent almost two years there whereas Emily returned for Aunt Branwell’s funeral in the autumn of 1842 and remained in Haworth thereafter) were turbulent yet formative ones. She found love with Monsieur Constantin Heger, who was first her teacher and then her colleague, but it was not reciprocated, and she also lost her beloved friend Martha Taylor who was also in Brussels at the time.

These events were searingly painful for Charlotte; they changed her life for ever, and yet they changed her writing too. We see Martha as Jessy Yorke in Shirley, and her Belgian funeral is referenced twice in Villette. Heger casts an even larger shadow, as he can be seen in all Charlotte’s heroes and anti-heroes, most notably as Rochester and Paul Emanuel.

Charlotte’s letters to Constantin after she has left Belgium are difficult to read, and not only because they were at one point cut into pieces before being stitched back together again. For those of us who love Charlotte and her writing it is terrible to witness her heart in such turmoil, but as always her letters are brutally honest. We see her begging her love to write back to her, as on 8th June 1845:

‘I know that you will lose patience when you read this letter. You will say that I am over-excited – that I have black thoughts etc. So be it Monsieur. I do not seek to justify myself, I submit to all kinds of reproaches – all I know is that I cannot – I will not resign myself to the total loss of my master’s friendship – I would rather undergo the greatest bodily pains than have my heart constantly lacerated by searing regrets.’

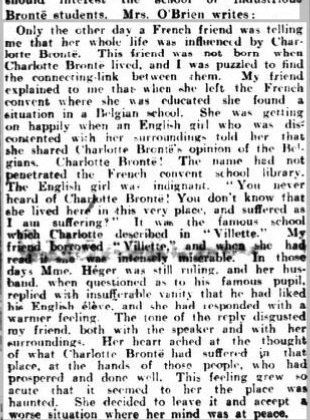

Charlotte begged for reproaches, even they would be better than the terrible silence which she had then endured for a year and a half, but reply came there none. We know, of course, that Charlotte Brontë had nothing to reproach herself for, other than a heart encountering the torments of love for the first time. Monsieur Heger, however, may not have been completely blame-free. 1915 saw a Scottish newspaper, the Carluke and Lanark Gazette, print a letter from a correspondent whose friend served as a teacher at the Heger school many years after Charlotte had. Her friend had found Heger’s vain and unfeeling attitude towards his conquest of Charlotte so distasteful, that she left her job:

Finally, we come to Emily Brontë. The months that Emily spent in Brussels were a struggle, and yet she conquered her demons in a way that she had been unable to when younger in Mirfield. Emily’s skills as a pianist were soon noted, and the Hegers not only arranged for her to receive tuition from a leading Brussels musician Monsieur Chapelle, they also hired Emily to teach the piano to other pupils.

Charlotte’s letters from Brussels to Ellen Nussey back in England at first revealed her worry that Emily would struggle as she knew not a word of French, and lessons were conducted solely in that language. She also wrote that Emily and Constantin Heger didn’t get on, and yet she soon won the hard hearted tutor over with her brilliance. He said of Emily that: ‘She should have been a man – a great navigator. Her powerful reason would have deduced new spheres of discovery from the knowledge of the old; and her strong, imperious will would never have been daunted by opposition or difficulty; never have given way but with life.’

Perhaps in her strength of character he found a kindred spirit in Emily, but he could never hope to match her brilliant mind. Wuthering Heights is not the only prose writing we have from Emily, for we also have a selection of her French language essays, or devoirs. When reading them now, translated into English by Sue Lonoff, it is incredible to think that she wrote them without any access to a dictionary, and within weeks of starting to learn the language.

They are miniature masterpieces that always take a philosophical turn. For example, when she was asked to write a devoir on ‘the butterfly’, she wrote:

‘During my soliloquy I picked a flower at my side; it was fair and freshly opened, but an ugly caterpillar had hidden itself among the petals and already they were shrivelling and fading. “Sad image of the earth and its inhabitants!” I exclaimed. “This worm lives only to injure the plant that protects it. Why was it created, and why was man created? He torments, he kills, he devours; he suffers, dies, is devoured – there you have his whole story.”’

We see a similar theme when Emily is asked to write about a cat. Her essay ‘Le chat’ was written again within weeks of her first encounter with the French language; not for Emily are platitudes such as ‘the cat has whiskers’ or ‘the cat is black with four legs’. Emily eschews the bland and instead produces sheer brilliance:

‘A cat, in its own interest, sometimes hides its misanthropy under the guise of amiable gentleness; instead of tearing what it desires from its master’s hand it approaches with a caressing air, rubs its pretty little head against him, and advances a paw whose touch is as soft as down. When it has gained its end, it resumes its character of Timon; and that artfulness in it is called hypocrisy. In ourselves, we give it another name, politeness, and he who did not use it to hide his real feelings would soon be driven from society. “But,” says some delicate lady, who has murdered half a dozen lap-dogs through pure affection, “the cat is such a cruel beast, he is not content to kill his prey, he torments it before its death; you cannot make that accusation against us.” More or less, Madam. Your husband, for example, likes hunting very much, but foxes being rare on his land, he would not have the means to pursue this amusement often, if he did not manage his supplies thus: once he has run an animal to its last breath, he snatches it from the jaws of the hounds and saves it to suffer the same infliction two or three more times, ending finally in death. You yourself avoid the bloody spectacle because it wounds your weak nerves. But I have seen you embrace your child it transports, when he came to show you a beautiful butterfly crushed between his cruel fingers; and at that moment, I really wanted to have a cat, with the tail of a half-devoured rat hanging from its mouth to present as the image, the true copying of your angel.’

It is incredible to think that Emily wrote all this in perfect French, so there is little wonder that Constantin Heger soon became awed by her abilities. We think also of Charlotte explaining that whilst Emily mixed little with the people in the outside world, somehow she knew them. It also brings to mind Ellen Nussey’s assertion that Emily was to her without doubt the greatest genius of the first half of the century.

Emily Brontë had a unique and powerful mind, if only she had lived to write other novels than Wuthering Heights there can be little doubt that they would all have been masterpieces. Like her sister Charlotte her time in Brussels changed her life forever, and those changes would find their way onto the pages of the books the whole world now loves.