March is Women’s History Month, and today is International Women’s Day, so today we’re going to look at a woman who achieved a lot in many different fields. We’re also going to see how she was influenced by the Brontës, and by Anne Brontë in particular. Born Mary Amelia St. Clair on the Wirral in 1863, she became better known as May Sinclair.

May Sinclair was one of the great polymaths of the late nineteenth and early twentieth centuries, and her talents deserve to be recognised as much now as they were then. Her early life echoed the Brontës, in that it started full of promise but encountered early tragedy. May’s father was a wealthy shipping magnate, but he was also an alcoholic and eventually lost all his money. Her mother was a strict and religious woman, but May was never one to blindly follow the rules of the day.

Her father’s downfall meant that May had to earn the money to look after herself and her mother, and she turned to her great passion: writing. In her writing as in life she was an innovator, and many of her works are seen as precursors of twentieth century modernism – she not only used stream of consciousness narratives, she is credited with inventing the term. May became popular on both sides of the Atlantic, and was hugely prolific. As well as writing 23 novels, 29 short stories, and a raft of excellent poetry, she also wrote essays, literary criticism and was a translator.

Other than two very special works as far as we’re concerned, which I will come to shortly, perhaps her most acclaimed novel was ‘The Combined Maze’, published in 1913, which takes a frank yet sympathetic look at an ordinary man who loves two women. The great thriller writer Agatha Christie called it one of the greatest of all novels, which is high praise indeed. May wasn’t averse to genre fiction herself, and became regarded as a master of supernatural and horror fiction. Like Arthur Conan-Doyle, she became very interested in spiritualism after the advent of the First World War and the horrors it brought with it, and was a member of The Society For Psychical Research.

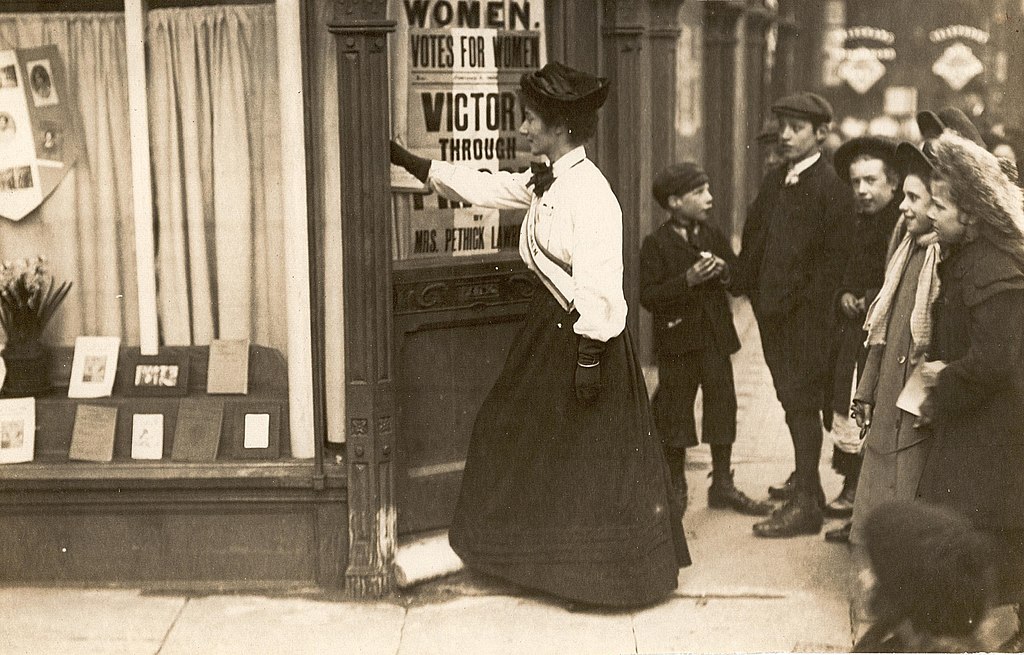

Perhaps May Sinclair is equally well known today for her activities as a suffragette. She was a friend of Sylvia Pankhurst, and was a vigorous supporter of the Suffrage movement, both on marches and at meetings, and in letters that she sent to newspapers. Famously, May also dressed up as Jane Austen for a suffragette fundraising event. The Suffragettes were quick to recognise the positive impact that women writers had had, as we can see from this photograph:

May was a great believer in equal rights for women, and she was also renowned for many other laudable acts, including being a founder of London’s Medico-Psychological Clinic (she was a great believer in psychology and the teachings of Sigmund Freud). At the outbreak of war in 1914, it was inevitable that a woman of action such as May was would play her part. She volunteered to serve with the Munro Ambulance Corps, and spent time on the Western Front in Flanders. It was during this time that she wrote incredibly powerful war poetry, such as ‘After The Retreat’:

“If I could only see again

The house we passed on the long Flemish road

That day

When the Army went from Antwerp, through Bruges, to the sea;

The house with the slender door,

And the one thin row of shutters, grey as dust on the white wall.

It stood low and alone in the flat Flemish land,

And behind it the high slender trees were small under the sky.

It looked

Through windows blurred like women’s eyes that have cried too long.

There is not anyone there whom I know,

I have never sat by its hearth, I have never crossed its threshold, I have never opened its door,

I have never stood by its windows looking in;

Yet its eyes said: ‘You have seen four cities of Flanders:

Ostend, and Bruges, and Antwerp under her doom,

And the dear city of Ghent;

And there is none of them that you shall remember

As you remember me.’

I remember so well,

That at night, at night I cannot sleep in England here;

But I get up, and I go:

Not to the cities of Flanders,

Not to Ostend and the sea,

Not to the city of Bruges, or the city of Antwerp, or the city of Ghent,

But somewhere

In the fields

Where the high slender trees are small under the sky –

If I could only see again

The house we passed that day.”

May personally witnessed the horrors of war, and saw vast numbers of men wounded and killed – yet she sees too the cost that brought to women, so that the windows of a house are burned forever in her mind – they ‘look like women’s eyes that have cried too long’.

May Sinclair was a first class poet, a writer of brilliance, possessor of an incredibly powerful mind and a burning passion for making society better and fairer, and throughout it all she took inspiration from the Brontës, and especially from Anne’s ‘The Tenant Of Wildfell Hall‘. In an essay appraising Anne’s second novel, it was May who famously wrote that ‘the slamming of Helen’s bedroom door against her husband reverberated throughout Victorian England.’

May Sinclair’s great love for the Brontës of Haworth can also be clearly seen in two of her books, both very different but bearing very similar titles. ‘The Three Brontës’ was May’s biography of the sisters, published in 1912. It is beautifully written and in many ways important, because May redresses some of the claims made against Patrick Brontë, and reveals him as a good father. She also emphasises the huge influence that Haworth and its moors had upon the Brontës’ writing, as we can see from this exquisitely crafted opening:

‘It is impossible to write of the three Brontës and forget the place they lived in, the black-grey, naked village, bristling like a rampart on the clean edge of the moor; the street, dark and steep as a gully, climbing the hill to the Parsonage at the top; the small oblong house, naked and grey, hemmed in on two sides by the graveyard, its five windows flush with the wall, staring at the graveyard where the tombstones, grey and naked, are set so close that the grass hardly grows between. The church itself is a burying ground; its walls are tombstones, and its floor roofs the forgotten and the unforgotten dead. A low wall and a few feet of barren garden divide the Parsonage from the graveyard, a few feet between the door of the house and the door in the wall where its dead were carried through. But a path leads beyond the graveyard to “a little and a lone green lane”, Emily Brontë’s lane that leads to the open moors. It is the genius of the Brontës that made their place immortal; but it is the soul of the place that made their genius what it is.’

This eminently readable biography was neither the first or last time time that May Sinclair turned to the Brontës in her writing, but she later did so in disguise. Just as Patrick had made the young Brontës wear masks as he questioned them, and as they later wore the masks of Currer, Ellis and Acton Bell to write their novels, May Sinclair wrote a novel about them – obscuring them with masks of her own creation.

‘The Three Sisters’ was published in 1914. In it, May tells the story of three sisters, Mary, Gwendolen and Alice Cartaret. They live in a parsonage at the moorside village of Garth, where there father is the aging curate. Over the course of the novel they all fall in love with the same man, and this brings about the fall of their sororal bonds and a break up of their family.

The sisters are not facsimiles of Charlotte, Emily and Anne – the youngest Alice, for example, is a sensualist. Even so, we can see from the description of the sisters more than a hint of the Brontës of Haworth:

‘Mary, the eldest, sat in a low chair by the fireside. Her hands were clasped loosely on the black woolen socks she had ceased to darn. She was staring into the fire with her gray eyes, the thick gray eyes that never let you know what she was thinking. The firelight woke the flame in her reddish-tawny hair. The red of her lips was turned back and crushed against the white. Mary was shorter than her sisters, but she was the one that had the colour. And with it she had a stillness that was not theirs. Mary’s face brooded more deeply than their faces, but it was untroubled in its brooding. She had learned to darn socks for her own amusement on her eleventh birthday, and she was twenty-seven now.

Alice, the youngest girl (she was twenty-three) lay stretched out on the sofa. She departed in no way from her sister’s type but that her body was slender and small boned, that her face was lightly finished, that her gray eyes were clear and her lips pale against the honey-white of her face, and that her hair was colorless as dust except where the edge of the wave showed a dull gold. Alice had spent the whole evening lying on the sofa. And now she raised her arms and bent them, pressing the backs of her hands against her eyes. And now she lowered them and lifted one sleeve of her thin blouse, and turned up the milk-white under surface of her arm and lay staring at it and feeling its smooth texture with her fingers.

Gwendolen, the second sister, sat leaning over the table with her arms flung out on it as they had tossed from her the book she had been reading. She was the tallest and the darkest of the three. Her face followed the type obscurely; and vividly and emphatically it left it. There was dusk in her honey-whiteness, and dark blue in the gray of her eyes. The bridge of her nose and the arch of her upper lip were higher, lifted as it were in a decided and defiant manner of their own. About Gwenda there was something alert and impatient. Her very supineness was alive. It had distinction, the savage grace of a creature utterly abandoned to a sane fatigue. Gwenda had gone fifteen miles over the moors that evening. She had run and walked and run again in the riotous energy of her youth.’

These physical and mental characteristics, and the ages, align with the Brontës – as does the location they find themselves in. It is clear that May Sinclair has taken her beloved Brontës as the basis for her characters, but then put them in a situation very different to the one they found themselves in. The novel is long, complex but fascinating. May’s love of psychology can clearly be seen, as can her fascination with what humans are capable of if society was fairer and allowed them to achieve their full potential.

May Sinclair was a trailblazer, a brilliant writer and a brilliant woman, so today is a perfect day to remember her. Thank you May Sinclair, and thank you all for your lovely reaction to last week’s post – I’ve had so many great suggestions for future posts, so keep your eyes peeled.

Today is International Women’s Day but of course the truth is that this isn’t merely a day for women to celebrate, it’s a day for everyone to celebrate. Have a great day, and a great Women’s History Month.