The exact date remains a mystery, but we know that in May 1832, just under a year and a half after commencing her education there, Charlotte Brontë left Roe Head School in Mirfield. Her studies were complete, but once back home in Haworth she had to step into a new role that so many are currently facing: she became a home schooling teacher to her younger sisters Emily and Anne.

In July 1832 Charlotte described a typical day as a home schooler in a letter to her friend Ellen Nussey, a fellow Roe Head pupil just two months earlier. The routine Charlotte describes has become familiar to parents across the United Kingdom and beyond:

“You ask me to give you a description of the manner in which I have passed every day since I left School: this is soon done as an account of one day is an account of all. In the morning from nine o’clock till half past twelve I instruct my sisters and draw, then we walk till tea-time, and after tea I either read, write, do a little fancy-work or draw, as I please. Thus in one delightful, though somewhat monotonous course my life is passed.”

Charlotte’s role of teacher to her sisters was born not out of any epidemic of course (even though Haworth suffered from them on an annual basis) but necessity. In short, Patrick couldn’t afford to send all of his daughters to school at this time, so he hoped that once Charlotte herself had gained sufficient knowledge she could pass it on to Emily and Anne.

Just what did the young sisters’ lessons consist of at the hands of teacher Charlotte? We can imagine that needlework classes were still very much in the hands of Aunt Branwell, as we looked at in a recent post, so Charlotte’s lessons would have been based on those she had sat through at Roe Head. These in turn were based upon a book that had revolutionised education in England, and it was written by a woman who herself was associated with the West Riding of Yorkshire: Richmal Mangnall.

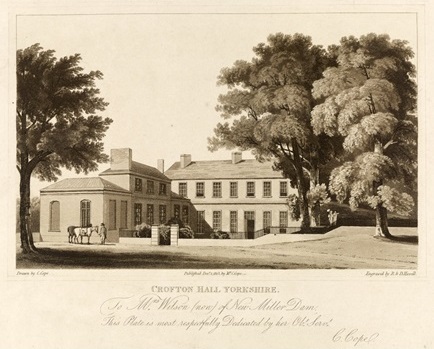

Richmal was born on 7th March 1769. There is no record of where she was born, but we know that she became a pupil at the grand Crofton Hall School in Wakefield (that’s it at the head of this post). There she took the path which Charlotte later followed, graduating from being a pupil to being a teacher, although Richmal relished this progression. She not only taught classes at Crofton Hall, and eventually became its headmistress, she also set down the basis of a comprehensive curriculum for school children in a book entitled Historical And Miscellaneous Questions For The Use Of Young People.

Published in 1798, it contained historic and scientific facts and a series of questions and answers that pupils could learn by rote. It proved incredibly popular, bringing great fame to its author too and it didn’t take long for the book to become known simply as Mangnall’s Questions. Richmal died in 1820 but her book dominated schooling in this country throughout the first half of the nineteenth century – by 1857 Mangnall’s Questions was in its 84th printed edition.

Crofton Hall School had a reputation as one of the best in the country, but it no longer stands. A blue plaque, however, marks its location and its famed headmistress – as well as two former pupils that are of interest to us: “On this site stood Crofton Hall School. Miss Mangnall, headmistress 1808-1820, through her world renowned book ‘Historical & Miscellaneous Questions’, informed and enthused teachers and pupils (including the Brontë children) throughout the 19th century.”

Mangnall’s Questions formed the basis of lessons at Roe Head just as it did at many schools, and therefore it would have been used by Charlotte in Haworth Parsonage too. The plaque also refers to Maria and Elizabeth Brontë who had attended Crofton Hall for a term. Alas, even with the support of Anne’s godmothers Elizabeth Firth and Fanny Outhwaite, who had attended the school themselves and probably subsidised some of Maria and Elizabeth’s fees, this excellent school proved beyond the finances of Patrick Brontë for any longer than a term.

Charlotte, like Richmal had done at her school, returned to Roe Head to serve as a teacher. It was July 1835, and under the terms of her contract she was allowed to take with her one of her sisters to receive a free education at the school. Being older, Emily was naturally first choice for this boon, but we all know how extreme home sickness soon forced her to leave Mirfield and return to Haworth. Anne Brontë took her place, and she soon excelled at her lessons. Without Charlotte returning to the school as a teacher, however, it is likely that Anne would have received no formal school-based education at all.

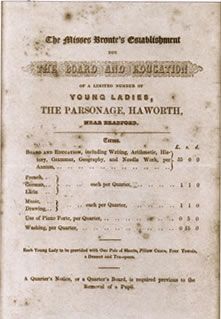

Nevertheless, Anne had been taught well in Haworth Parsonage thanks to the teachings of Charlotte, her aunt and her father. The Brontë sisters later tried to put their learning to good use by opening their own school based within the parsonage – the ‘Misses Brontë’s Establishment for the Board and Education of a Limited Number of Young Ladies’. No pupils could be secured, and the scheme had to be set aside to be replaced eventually by another plan that the three sisters could share: writing.

Compulsory state education was drawing near, and the days of home-schooling as the norm were coming to an end forever – or so we thought. Stay healthy, happy and alert and I will see you here again next Sunday for another new blog post – oh, and if you’re currently home schooling your own children and are running out of lesson ideas then there’s a highly useful book still available right now on Amazon: Historical And Miscellaneous Questions For The Use Of Young People by Richmal Mangnall.

Thank you so much for this post! It’s very interesting to see how the lifes of the sisters, reflected on their work.