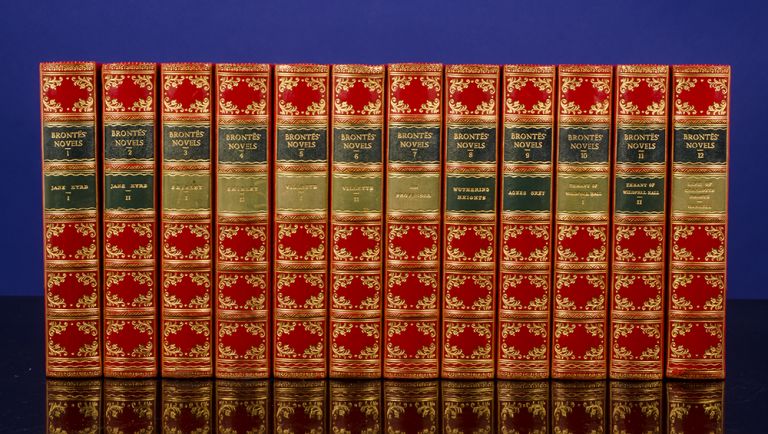

We’ve entered what is often called ‘Flaming June’ – the month that marks the beginning of meteorological summer. Of course, as we’d expect from the sort of year 2020 has become June has announced herself not with hot, sunny days but with downpours and gusts. After record breaking temperatures in April and May, when most of us were firmly locked down, now the first few Covid parolees are stumbling blinking through their doors we seem to have reverted to north-pole days once again. Such is the year we find ourselves in, but at least we will always have great books to divert and console us. In this week’s Brontë blog post we’re going to look at the month of June in the novels of the Brontës.

Jane Eyre

‘It was the first of June; yet the morning was overcast and chilly: rain beat fast on my casement. I heard the front-door open, and St. John pass out. Looking through the window, I saw him traverse the garden. He took the way over the misty moors in the direction of Whitcross – there he would meet the coach.

“In a few more hours I shall succeed you in that track, cousin,” thought I: “I too have a coach to meet at Whitcross. I too have some to see and ask after in England, before I depart for ever.” It wanted yet two hours of breakfast-time. I filled the interval in walking softly about my room, and pondering the visitation which had given my plans their present bent. I recalled that inward sensation I had experienced: for I could recall it, with all its unspeakable strangeness. I recalled the voice I had heard; again I questioned whence it came, as vainly as before: it seemed in me – not in the external world. I asked was it a mere nervous impression – a delusion? I could not conceive or believe: it was more like an inspiration. The wondrous shock of feeling had come like the earthquake which shook the foundations of Paul and Silas’s prison; it had opened the doors of the soul’s cell and loosed its bands – it had wakened it out of its sleep, whence it sprang trembling, listening, aghast; then vibrated thrice a cry on my startled ear, and in my quaking heart and through my spirit, which neither feared nor shook, but exulted as if in joy over the success of one effort it had been privileged to make, independent of the cumbrous body.

“Ere many days,” I said, as I terminated my musings, “I will know something of him whose voice seemed last night to summon me. Letters have proved of no avail – personal inquiry shall replace them.”’

In Jane Eyre the start of June sees our eponymous heroine decide to track down Rochester after seeming to hear his voice calling to her. The rest is history, so I don’t think I will be spoiling too much if I say that reader, she married him.

Wuthering Heights

‘On the morning of a fine June day my first bonny little nursling, and the last of the ancient Earnshaw stock, was born. We were busy with the hay in a far-away field, when the girl that usually brought our breakfasts came running an hour too soon across the meadow and up the lane, calling me as she ran.

“Oh, such a grand bairn!” she panted out. “The finest lad that ever breathed! But the doctor says missis must go: he says she’s been in a consumption these many months. I heard him tell Mr. Hindley: and now she has nothing to keep her, and she’ll be dead before winter. You must come home directly. You’re to nurse it, Nelly: to feed it with sugar and milk, and take care of it day and night. I wish I were you, because it will be all yours when there is no missis!”’

In Wuthering Heights Frances has given birth to a son who we will later come to know as Hareton, but giving birth signals her own death, just as it will for Catherine after the birth of Cathy. At the climax of the novel these two children, now adults, will themselves find love and redemption and the endless cycle of birth, death and rebirth that Emily Brontë saw in nature will continue.

Agnes Grey

‘The 1st of June arrived at last: and Rosalie Murray was transmuted into Lady Ashby. Most splendidly beautiful she looked in her bridal costume. Upon her return from church, after the ceremony, she came flying into the schoolroom, flushed with excitement, and laughing, half in mirth, and half in reckless desperation, as it seemed to me.

“Now, Miss Grey, I’m Lady Ashby!” she exclaimed. “It’s done, my fate is sealed: there’s no drawing back now. I’m come to receive your congratulations and bid you good-by; and then I’m off for Paris, Rome, Naples, Switzerland, London – oh, dear! what a deal I shall see and hear before I come back again. But don’t forget me: I shan’t forget you, though I’ve been a naughty girl. Come, why don’t you congratulate me?”’

Agnes finds it hard to congratulate her charge because she has married for position and not for love. The same battle was played out in real life, as the Robinson girls often wrote to their former governess Anne Brontë for advice on the matches their mother had made for them. Anne gave the same advice as Agnes – follow your heart, don’t marry for wealth or status. We know this from a letter Charlotte wrote to Ellen Nussey in July 1848:

‘Anne continues to hear constantly – almost daily, from her old pupils, the Robinsons. They are both now engaged to different gentlemen and if they do not change their minds, which they have already done two or three times, will probably be married in a few months. Not one spark of love does either of them profess for her future husband… Anne does her best to cheer and counsel her [Bessie Robinson] and she seems to cling to her quiet, former governess as her only true friend.’

Bessie certainly listened to Anne’s advice, much to her mother Lydia’s chagrin. She had been betrothed to Henry Milner, a wealthy mill owner’s son, but the engagement was broken off. The Robinsons were sued by the Milners for breach of contract, and a court ordered them to pay the offended party the substantial sum of £90 in compensation. In Agnes Grey we see Rosalie regret her decision to marry, later inviting Agnes to visit her.

The Tenant Of Wildfell Hall

‘June 1st, 1821. – We have just returned to Staningley – that is, we returned some days ago, and I am not yet settled, and feel as if I never should be. We left town sooner than was intended, in consequence of my uncle’s indisposition; – I wonder what would have been the result if we had stayed the full time. I am quite ashamed of my new-sprung distaste for country life. All my former occupations seem so tedious and dull, my former amusements so insipid and unprofitable. I cannot enjoy my music, because there is no one to hear it. I cannot enjoy my walks, because there is no one to meet. I cannot enjoy my books, because they have not power to arrest my attention: my head is so haunted with the recollections of the last few weeks, that I cannot attend to them. My drawing suits me best, for I can draw and think at the same time; and if my productions cannot now be seen by any one but myself, and those who do not care about them, they, possibly, may be, hereafter. But, then, there is one face I am always trying to paint or to sketch, and always without success; and that vexes me. As for the owner of that face, I cannot get him out of my mind – and, indeed, I never try. I wonder whether he ever thinks of me; and I wonder whether I shall ever see him again. And then might follow a train of other wonderments – questions for time and fate to answer – concluding with – Supposing all the rest be answered in the affirmative, I wonder whether I shall ever repent it? as my aunt would tell me I should, if she knew what I was thinking about.’

In this extract from Anne Brontë’s second novel we find certain similarities with the extract from her first. Helen is secretly longing for what she then sees as a dashing suitor: Arthur Huntingdon. Her aunt, however, has given her the exact opposite advice that Agnes has given: don’t follow your heart, think of marriage as an opportunity for social advancement. Helen then follows a very different path from Rosalie Murray, and yet her marriage too is unhappy and abusive. Anne’s underlying message then is not to rush into marriage – whether you follow your heart or the money. That this is Anne’s heartfelt belief can also be seen in the conclusion of The Tenant Of Wildfell Hall. After Arthur’s death, Helen is finally free to marry Gilbert, but by following clues in the text we can see that Helen makes him wait a further 28 months before finally marrying him.

Four extracts from Brontë novels, three of which are specifically dated the 1st of June. They cover the whole spectrum of human life and emotions – birth, death, marriage, hopes that will turn to despair. June is a time of change and opportunity; it has always been such as such, and their writing shows just how much the Brontës believed in the transformative power of June and the start of summer. Let’s hope that things change for the better for our world in this particular June – there’s still time for this to be flaming June rather than flaming hopeless. Stay happy and healthy, I’ll see you with a new Brontë post next Sunday.

I really enjoyed this post! I’ve read all of these novels, but never saw the June connection. Thank you for this!

Fabulous post! I love that I know all the characters you write of, as if they are old friends. And all created by three sisters. It really is a marvel, when you stop and think about it. Thanks, Nick!