The old saying says that there are only two certainties in life: taxes and death. I think we can add a third: criticism. It doesn’t matter what we all do in life, somebody will find something to criticise us about, whether it be our skills as a parent, in a job, or in a creative endeavour. This latter criticism was something the Brontës had to face on many occasions, and unfortunately it was far from constructive. In today’s post we’re going to look at two prime examples of the criticism that Charlotte Brontë faced, and how, with a little help from a publishing house, she gained a belated yet rather unique revenge.

The critics misunderstood and attacked the Brontës because they were such powerful, original writers. Currer, Ellis and Acton Bell (as the critics believed Charlotte, Emily and Anne Brontë to be called) were writing with a brilliance, freshness and honesty that shocked many of the staid men and women whose job it was to pronounce judgement on the latest literary releases. Yes, women too were among the most vociferous critics of the Bells, and perhaps the most brutal and unfair critique of them all came from Elizabeth Rigby, later to become Lady Eastlake.

To be fair to her, some people have pointed out Elizabeth’s better qualities; it seems that she was very helpful to Effie Ruskin at the time she was undergoing marital difficulties with John Ruskin – the marriage was eventually annulled and Effie married the eminent Pre-Raphaelite John Millais. Elizabeth Rigby could be a good friend, but not to writers whose books she was reviewing. Wordsworth, for example, she denounces as, ‘ a puzzle to me – commonplace in thought and barren in word, yet with some he is more popular than any other poet.’ The great artist Turner was, ‘pertinacious and stupid.’

In December 1848, as a reviewer for the Quarterly Review she was given the task of reviewing Jane Eyre, and produced a review so shockingly lacking in astuteness that I have to reproduce it here:

‘The inconsistencies of Jane’s character lie mainly not in her own imperfections, though of course she has her share, but in the author’s. There is that confusion in the relations between cause and effect, which is not so much untrue to human nature as to human art. The error in Jane Eyre is, not that her character is this or that, but that she is made one thing in the eyes of her imaginary companions, and another in that of the actual reader. There is a perpetual disparity between the account she herself gives of the effect she produces, and the means shown us by which she brings that effect about. We hear nothing but self-eulogiums on the perfect tact and wondrous penetration with which she is gifted, and yet almost every word she utters offends us, not only with the absence of these qualities, but with the positive contrasts of them, in either her pedantry, stupidity, or gross vulgarity. She is one of those ladies who put us in the unpleasant predicament of undervaluing their very virtues for dislike of the person in whom they are represented. One feels provoked as Jane Eyre stands before us – for in the wonderful reality of her thoughts and descriptions, she seems accountable for all done in her name – with principles you must approve in the main, and yet with language and manners that offend you in every particular.

It would be mere hackneyed courtesy to call it ‘fine writing.’ It bears no impress of being written at all, but is poured out rather in the heat and hurry of an instinct, which flows ungovernably on to its object, indifferent by what means it reaches it, and unconscious too. As regards the author’s chief object, however, it is a failure – that, namely, of making a plain, odd woman, destitute of all the conventional features of feminine attraction, interesting in our sight. We deny that he has succeeded in this.

Jane Eyre is throughout the personification of an unregenerate and undisciplined spirit… altogether an anti-Christian composition… the impression she leaves on our mind is that of a decidedly vulgar-minded woman – one whom we should not care for as an acquaintance, whom we should not seek as a friend, whom we should not desire for a relation, and whom we should scrupulously avoid for a governess… No lady, we understand, when suddenly roused in the night, would think of hurrying on ‘a frock.’ They have garments more convenient for such occasions, and more becoming too… if we ascribe the book to a woman at all, we have no alternative but to ascribe it to one who has, for some sufficient reason, long forfeited the society of her own sex. And if by no woman, it is certainly also by no artist… We do not hesitate to say that the tone of mind and thought which has overthrown authority and violated every code human and divine abroad, and fostered Chartism and rebellion at home, is the same which has also written Jane Eyre.’

These are just the, ahem, highlights, as Elizabeth Rigby’s review is over 15,000 words in length – almost a novella in itself. It should be said, however, that this long review also incorporates a scathing appraisal of Thackeray’s Vanity Fair, and it also addresses the rumour ‘current in Mayfair’ (which Elizabeth dismisses) that Jane Eyre has been written by a maid in the service of Thackeray.

Imagine the impact that this review had on Charlotte – seeing her work dismissed as coarse and of little value, and herself dismissed as a woman of low morals. This was by no means uncommon in reviews of Charlotte and her sisters at the time, and this criticism even continued in the aftermath of Charlotte’s death.

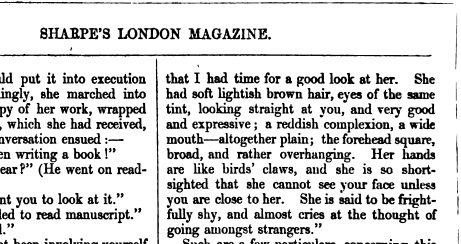

In June 1855, just two months after her passing, Sharpe’s London Magazine printed an article examining the author’s life and work entitled, ‘A Few Words About “Jane Eyre”:

‘Some eight years since, a novel, in three volumes, emanating from the shelves of, if we are not mistaken, Messrs. Smith and Elder, found its way, by their influence, into the circulating libraries; and, in due course of time, met with readers, and became famous. But the strange thing was, that no two people could agree with their opinions of it, so full was it of contradictions. Miss A. was delighted with it, Miss B. as much disgusted – Miss C. heard it so talked of, that she was most anxious to read it; but her married sister, Mrs. D, said, “No woman under thirty ought to open it.”’

This critic also attack Rochester’s use of, ‘real wicked oaths, like a bold, bad, live man:

‘All this was very odd and incorrect; the novel-reading public had become accustomed to the “fiends and furies” style; believed in it as the common language to the aristocracy of nature, and associated all plainer speaking with pot-house company, skittles and unlimited beer and tobacco. So the public clamoured at this glimpse of nature thus unceremoniously revealed to them, very much as they would have clamoured if the writer had chosen to go to the opera sans culottes [‘without pants’]’

Having monstered Jane Eyre the magazine then prints a number of blatant untruths about the Brontë family history – stating, for example, that Patrick Brontë had been a minister in Penzance and met Maria Branwell there, but that her family turned their back on her because of the marriage. In truth, of course, Patrick never went to Cornwall, and far from shunning Maria a member of the Branwell family, Elizabeth, visited them in Thornton for over a year, and eventually became resident in Haworth Parsonage. The magazine also gave a most unflattering portrait of Charlotte’s physical features, which you can see below:

Charlotte’s great friend Ellen Nussey was distraught when she read this article; so much so that she wrote to Charlotte’s widow Arthur Bell Nicholls and begged him to write to Elizabeth Gaskell asking her to produce an authorised Brontë biography. Arthur was less than keen on this idea, possibly because he and Ellen were on far from friendly terms, so Ellen next wrote to Patrick Brontë who was much more receptive to the scheme. He wrote to Elizabeth Gaskell and the result, of course, was her The Life Of Charlotte Brontë.

The criticism the Brontës received was unfair and unmerited, and we can be sure that it hit home. I recall an interview between Michael Parkinson and the brilliant poet laureate John Betjeman in which he talked of the negative criticism he’d received:

‘I always believe it’s true. I believe anything that’s said against me is true, and anything said in my favour is flattery. I never can believe that I’m any good at all.’

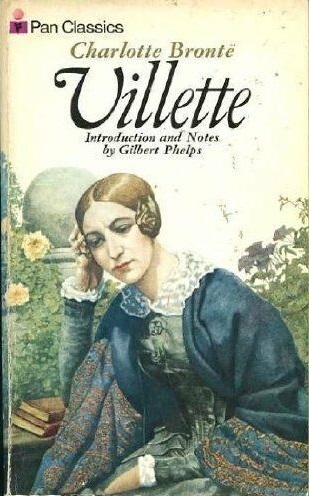

The truth is that Betjeman was very good indeed, as were the Brontës, and that must have made the criticism, and especially the personal attacks, even harder to bear. Anne Brontë looked her critics straight in the face, and hit back in brilliant fashion in her preface to the second edition of The Tenant Of Wildfell Hall; Emily Brontë met the attacks with her customary stoicism, but the effects of the cruel words can perhaps be seen in the fact that she wrote no new work after the publication of Wuthering Heights, other than the reworking of an earlier poem. And Charlotte? Well for Charlotte, revenge was served cold. Do you remember that photograph of Elizabeth Rigby earlier? This week I purchased another edition of Villette for my Brontë collection – it was published by Pan Classics in 1973. Take a look at the cover star – I wonder what Lady Eastlake would have thought of her picture being used to illustrate a novel by an author who she felt had ‘long forfeited the society of her own sex’?

I believe it’s game, set and match to Charlotte. Stay happy and healthy, and I hope you can join me next Sunday for my next Brontë blog post.

Ha, so well researched and written. I will NOT criticise your blog.

Insightful. Sad but predictable. Criticism feels so good on the tongue initially. Yet years later it reflects the nature of the one who says it far better than a photograph.

I did not know of this ‘novella’ by Rigby.

I would like to read it.

As always, I appreciate your posts on the Brontes and Charlotte in particular as I am a lifelong, dyed-in-the-wool, card carrying fan of her Jane Eyre!