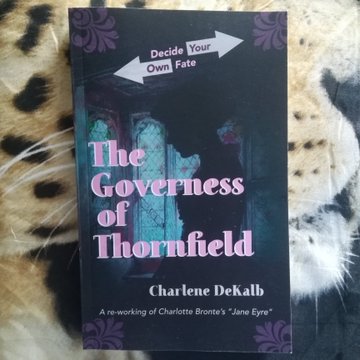

As we all know, the Brontë novels are full of great scenes and great characters, which is why we can read them time and time again and never tire of them. Some of these characters and scenes were drawn from real life, which is why researching the Brontës’ life and times can be as rewarding and fascinating. In today’s post we’re going to look at the Haworth fortune teller and their influence on Jane Eyre.

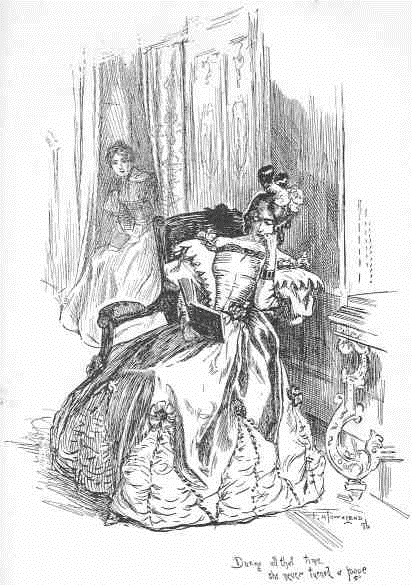

Who can forget the mysterious fortune teller who appears at Thornfield Hall and proceeds to tell the fortunes of first Blanche Ingram and finally Jane Eyre herself:

‘The library looked tranquil enough as I entered it, and the Sibyl – if Sibyl she were – was seated snugly enough in an easy-chair at the chimney-corner. She had on a red cloak and a black bonnet: or rather, a broad-brimmed gipsy hat, tied down with a striped handkerchief under her chin. An extinguished candle stood on the table; she was bending over the fire, and seemed reading in a little black book, like a prayer-book, by the light of the blaze: she muttered the words to herself, as most old women do, while she read; she did not desist immediately on my entrance: it appeared she wished to finish a paragraph.

I stood on the rug and warmed my hands, which were rather cold with sitting at a distance from the drawing-room fire. I felt now as composed as ever I did in my life: there was nothing indeed in the gipsy’s appearance to trouble one’s calm. She shut her book and slowly looked up; her hat-brim partially shaded her face, yet I could see, as she raised it, that it was a strange one. It looked all brown and black: elf-locks bristled out from beneath a white band which passed under her chin, and came half over her cheeks, or rather jaws: her eye confronted me at once, with a bold and direct gaze.

“Well, and you want your fortune told?” she said, in a voice as decided as her glance, as harsh as her features.

“I don’t care about it, mother; you may please yourself: but I ought to warn you, I have no faith.”

“It’s like your impudence to say so: I expected it of you; I heard it in your step as you crossed the threshold.”

“Did you? You’ve a quick ear.”

“I have; and a quick eye and a quick brain.”

“You need them all in your trade.”

“I do; especially when I’ve customers like you to deal with. Why don’t you tremble?”

“I’m not cold.”

“Why don’t you turn pale?”

“I am not sick.”

“Why don’t you consult my art?”

“I’m not silly.”

The old crone “nichered” a laugh under her bonnet and bandage; she then drew out a short black pipe, and lighting it began to smoke. Having indulged a while in this sedative, she raised her bent body, took the pipe from her lips, and while gazing steadily at the fire, said very deliberately—“You are cold; you are sick; and you are silly.”

“Prove it,” I rejoined.

“I will, in few words. You are cold, because you are alone: no contact strikes the fire from you that is in you. You are sick; because the best of feelings, the highest and the sweetest given to man, keeps far away from you. You are silly, because, suffer as you may, you will not beckon it to approach, nor will you stir one step to meet it where it waits you.”’

Of course this fortune teller turns out to be Rochester in disguise, but we get a good description of the art of those whose palms were crossed with silver. How did Charlotte Brontë know so much about fortune tellers? The truth is that there was a celebrated example in her own village of Haworth.

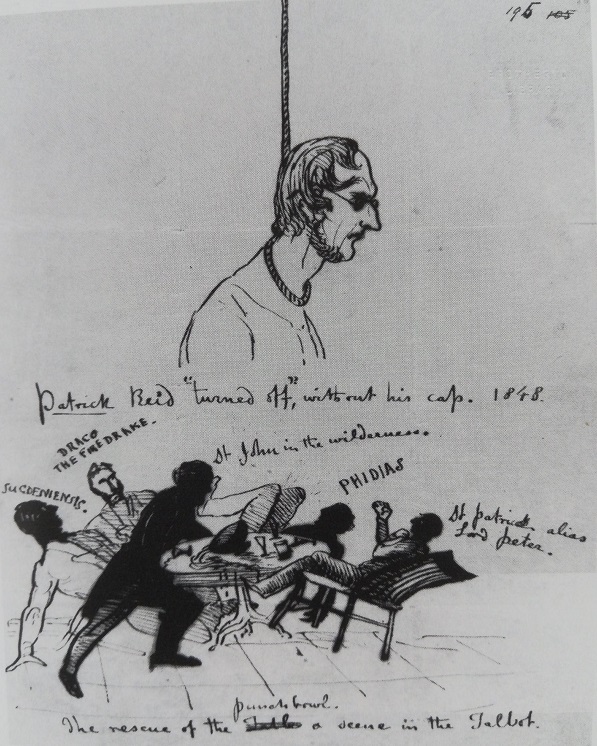

Whilst Charlotte, Emily and Anne may or may not have visited the wise person of Haworth we can be sure that their brother Branwell did, and for evidence of this we turn to two biographies that we also looked at in last week’s post about Branwell Brontë and the Royal Academy. In Pictures Of The Past his great friend Francis Grundy gave the following account of their visit to the fortune teller:

‘There was an old fortune-teller at Haworth, ninety-five years of age, and Branwell and the “three curates” [his friends] used often to go and consult her. She was a wonderful old soul, and, I think, believed thoroughly in her arts. At any rate, she was visited, either in jest or earnest, by the “carriage people” of two counties; and we often took our day’s spree on horseback or in “trap” thitherward. Nay, she entirely altered the life of a friend of mine, a draughtsman, who was so impressed by her wonderful knowledge of him and his doings, that he went home from an interview with her and carried out all she had told him, even to marrying a girl.’

Francis Leyland, who had also known his subject personally, in The Brontë Family: With Special Reference To Patrick Branwell Brontë also remarks upon Haworth’s fortune teller:

‘At times, during his stay with the railway company, Branwell would drive over from Luddenden Foot to visit his family at the Haworth parsonage, having hired a gig for the purpose. Mr. Grundy sometimes accompanied him, and they would escape to the moors together, or pay curious visits to the old fortune-teller, with the curates. Then, says his friend, he was ‘at his best, and would be eloquent and amusing, though, on returning sometimes, he would burst into tears, and swear he meant to mend.’ This last statement is favourable to Branwell’s calm judgment upon himself. Few – and Branwell was one of the last – drift deliberately into wrong-doing.’

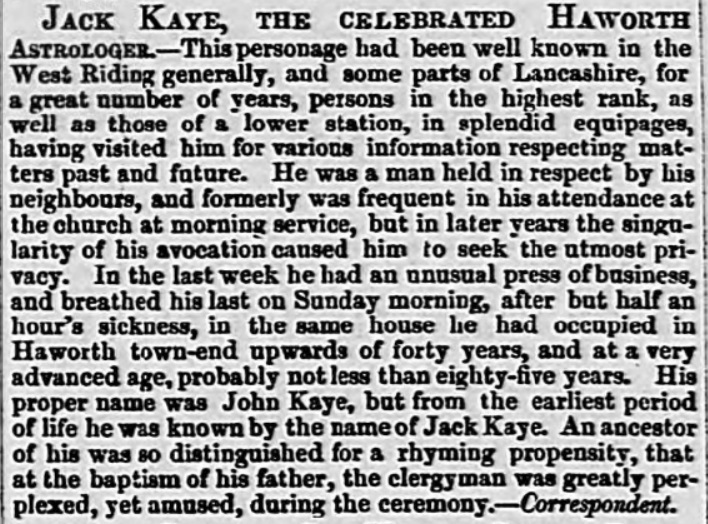

Can we get any more information on this mysterious personage consulted by Branwell Brontë, and revered by the leading personages of two counties? Once again, a plunge into the newspaper and genealogical archives can be revealing. Let’s start at the end and work backwards; the Leeds Intelligencer newspaper of 30th January 1847 carries the obituary of a Jack Kaye, ‘the celebrated Haworth astrologer’. Perhaps astrology was just one of his talents, or perhaps it was deemed a more suitable title than fortune teller? We find that he lives at Town End, Haworth and is very old, ‘probably not less than eighty-five years’. We also learn that he is consulted by the great and the good of two counties, just as Francis Grundy had said, and is held in respect by his Haworth neighbours – there can be little doubt that this is the person we’re looking for.

We also learn that his given name was John Kaye, but genealogy records reveal that he was actually born John Kay. He was buried, presumably by Patrick Brontë, in St. Michael and All Angels Church in Haworth on 28th January 1847. He was not 95 as Francis Grundy claimed, nor even 85 as the Leeds Intelligencer claimed, but was in fact born in 1767, putting him in his 80th year at the time of his passing (he was actually 79, as we shall see).

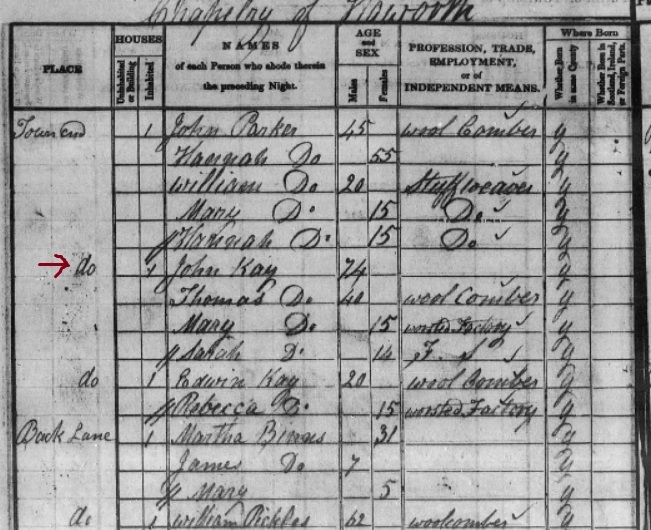

The 1841 census shows John Kay living, as his obituary said, at Town End in Haworth, just off what is now North Street. We get further confirmation of his year of birth being 1767 (unusually, as census enumerators in 1841 were told to round ages off to the nearest five years), and we see five further members of the Kay family living with him, presumably his son and grandchildren.

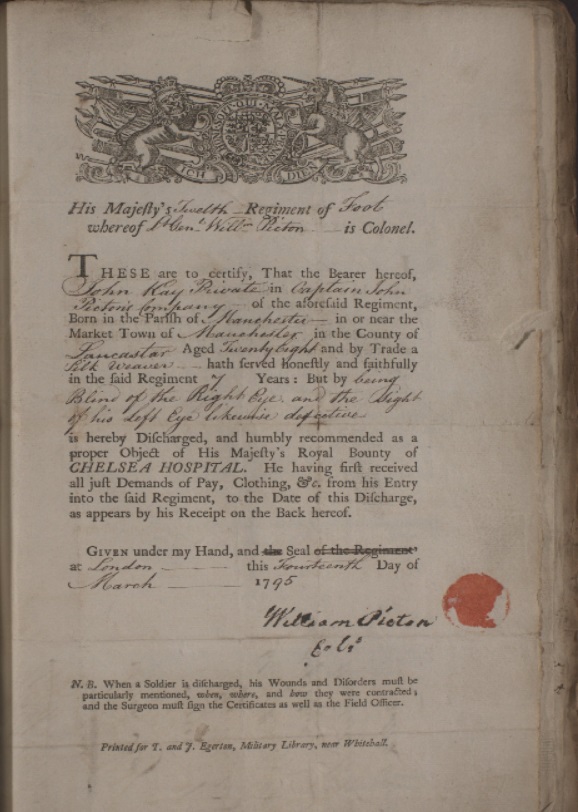

Heading back into the eighteenth century we can discover what our fortune teller did before following that vocation – he was a soldier in the King’s army. This fascinating record from 1795 is very revealing – originally born in Manchester (as we shall see) the 28 year old Private John Kay was previously a silk weaver, but has served for seven years in Captain John Picton’s company of the Twelfth Regiment of Foot of the Suffolk Regiment. He has served with honour but is being discharged because he is blind in his right eye and the sight in his left eye is now defective, possibly due to an injury sustained in combat? On the reverse side of this document we find that Kay has marked his signature with an X as he is unable to write.

Finally, I found John Kay’s baptismal record. On 7th June 1767 he was baptised in the parish church of Gorton, Lancashire – a southern suburb of Manchester. His father was Thomas Kay and his mother was named Ellin (which makes me think of Charlotte Brontë’s unfinished supernatural tinged novel Willie Ellin).

So now we know quite a lot more about the Wise Man of Haworth. Born in Manchester he was trained as a silk weaver but joined the army. He is partially blinded and after his discharge he makes his way to Haworth, a source of ready employment for skilled weavers. Perhaps his eyesight or the increasing industrialisation of the industry puts paid to Jack’s trade, so he turns to something else he has a skill for: telling fortunes. He is a great success, visited by people from across Yorkshire and Lancashire, including Branwell Brontë. It may even be thought likely that he was visited by Charlotte Brontë too when we read Jane Eyre and remember her love for phrenology – especially as his home in Town End was just a short walk from Haworth’s parsonage.

Certainly I think Jack Kay is the source of Rochester’s fortune telling endeavour. Only one mystery remains, Francis Grundy not only gets his age wrong but also his gender. It’s clear that Kay looked even older than his years, and perhaps when dressed in his fortune teller’s garbs he looked like a woman, or even affected that guise just as Rochester did?

You won’t find John Kay in Haworth today but it’s still a village where magic and the more arcane arts hang heavy in the air, and it’s all the better for that in my opinion. Have a great weekend, stay happy and healthy and remember to celebrate Emily Brontë’s birthday next Thursday. Please join me again for another new Brontë blog post next Sunday.