With lockdown restrictions being eased, many museums and art galleries are opening their doors to the public once more, and beautiful cities such as York and London are welcoming tourists once more (as is Haworth of course, although there’s no date for the reopening of the Brontë Parsonage Museum as yet). One London attraction that is always worth visiting is the Royal Academy of Arts which has re-opened to the public again, although its famous Summer Exhibition has been moved to October of this year. Controversy still reigns over whether Branwell Brontë ever attended the Royal Academy of Arts, or whether he made it to London at all, so that’s what we’re going to look at in today’s post.

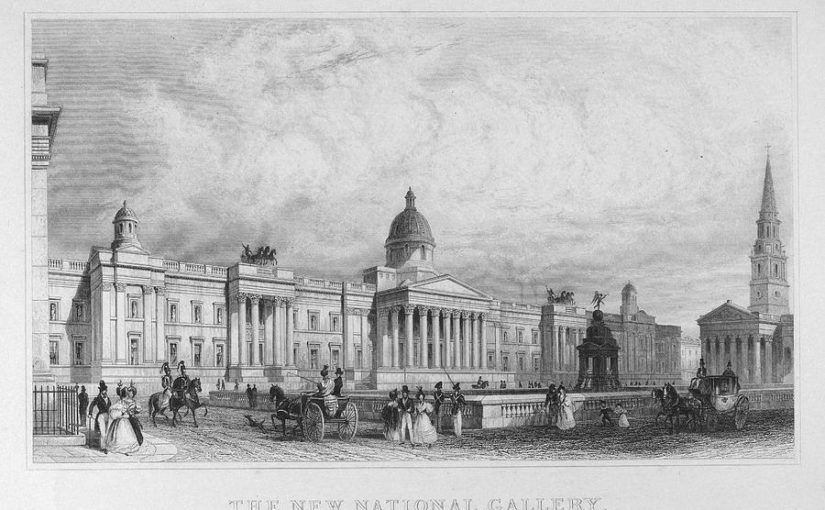

Two Brontës who we can be sure visited the Royal Academy are Charlotte and Anne Brontë. In July 1848 they travelled to London with the utmost haste in order to prove their true identity to Charlotte’s publisher George Smith. They then remained in London for four days, and among the places visited was the Royal Academy as Charlotte Brontë revealed in a letter to W.S. Williams after her return to Haworth:

‘I have just read your article in the John Bull; it very clearly and fully explains the cause of the difference obvious between ancient and modern paintings. I wish you had been with us when we went over the Exhibition and the National Gallery – a little explanation from a judge of Art would doubtless have enabled us to understand better what we saw; perhaps, one day, we may have this pleasure.’

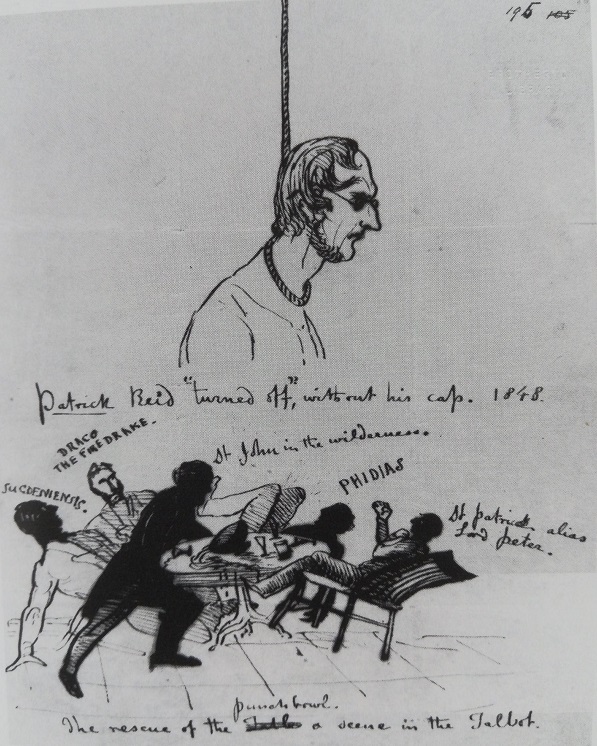

The Royal Academy is now housed in a beautiful building called Burlington House in Piccadilly, its home since 1868. At the time that Anne and Charlotte visited in 1848, however, it occupied a wing of the recently opened National Gallery in Trafalgar Square (that’s it at the head of this post, in the days before Nelson’s Column and the lions arrived). It was a place where the greatest artists of the land could exhibit their work to a discerning public, and also a place where promising young artists, for a fee, could learn their craft. It was for this reason that Branwell Brontë may have been sent to London in 1835. Certainly there is in existence a letter from Branwell to the Royal Academy in which he asks when he can attend and present samples of his work, but did he send the letter and did he even journey to London? Let’s examine the cases for the prosecution and the defence.

The prosecution would have it that Branwell Brontë never sent this draft letter and never travelled to London, and these people are invariably also of the camp that Branwell was not an artist of any talent or ability. This is the view expressed by Juliet Barker in her weighty tome The Brontës which has helped it become the prevailing opinion:

‘The Royal Academy has no record of this letter, a reply or any other correspondence with or about him.’

Juliet Barker then dismisses the testimony of Francis Grundy or Joseph Leyland that he had been to London (which we will come to presently), saying that they didn’t know him then. I would take issue with that, and other dismissive claims within this brilliant biography about Elizabeth Gaskell’s life of Charlotte Brontë. These people knew the subjects well and were friends with them, which is more than any present day biographer can say, so it seems to me folly to dismiss outright their opinions and stories which will have come from the mouths of the Brontës themselves.

The Brontë Society also now dismiss Branwell’s possible attendance at the Royal Academy outright, based on the same grounds, but surely this lack of proof nearly 200 years later is not proof that the event never happened? I believe that there is a significant amount of material that can be used in Branwell’s defence.

First, let’s look at the testimonies, beginning with that of Francis Grundy in Pictures Of The Past: Memories Of Men I Have Met. Would that everyone had a friend as kind and unbending as Francis Grundy, as his chapter on Branwell Brontë is a brilliant defence against the charges frequently laid against him then and now, including his touching conclusion that: ‘Patrick Branwell Brontë was no domestic demon – he was just a man moving in a mist, who lost his way.’

He also confirmed that Branwell had been in London: ‘Brontë drew a finished elevation of Westminster Abbey from memory, having been but once in London some years before. It was no mean achievement, for the sketch was correct in every particular.’

We next come to Francis Leyland, who had also been a friend of Branwell in his Halifax and Bradford days, and who was brother of the acclaimed sculptor Joseph Leyland. In his The Brontë Family, With Special Reference To Patrick Branwell Brontë he writes:

‘Branwell, in fact, designed to become himself a portrait-painter, and he conceived that a course of instruction at the Royal Academy afforded the best means of preparation for that profession. Being gifted with a keen and distinct observation, combined with the faculty of retaining impressions once formed, and being an excellent draughtsman, he could with ease produce admirable representations of the persons he portrayed on canvas. But it is quite clear that he never had been instructed either in the right mode of mixing his pigments, or how to use them when properly prepared, or, perhaps, he had not been an apt scholar. He was, therefore, unable to obtain the necessary flesh tints, which require so much delicacy in handling, or the gradations of light and shade so requisite in the painting of a good portrait or picture. Had Branwell possessed this knowledge, the portraits he painted would have been valuable works from his hand; but the colours he used have all but vanished, and scarcely any tint, beyond that of the boiled oil with which they appear to have been mixed, remains. Yet, even if Branwell had been fortunate in his work, he would only have attained the position, probably, of a moderate portrait-painter. His ambition, however, took a higher range, and he prepared himself for the venture, hoping that the desiderata which Haworth could not supply would be amply provided for him in London, when the long-desired opportunity arrived…

To London Branwell, however, went, where, without doubt, his object was to draw from the Elgin Marbles, and to study the pictures at the Royal Academy and other galleries, with a perfectly honest intention. Whatever impression he may have received of his own powers as an artist, when he saw those of the great painters of the time, we have no certain knowledge; but it does not exceed belief that he was discouraged when he looked upon the brilliant chef d’oeuvres of Sir Joshua Reynolds, Gainsborough, Sir Thomas Lawrence, and others; and that, when he reflected on the immeasurable distance between his own works and theirs, his hopes of a brilliant artistic career were partially dissipated. Whether it was due to these circumstances, or that he had become more fully aware of the early struggles that meet all who attempt art as a profession, or that his courage failed him at the contemplation of the unhappy lot which falls to those who, either from lack of talent or through misfortune, fail to make their mark in the artistic world; or whether it was because his father was unable to support him in London during the years of preparation and study for the professional career,—the requirements of which had not been sufficiently considered,—is not now accurately known. Branwell, during his short stay in London, visited most of the public institutions; and, among other places, Westminster Abbey, the western façade of which he some time afterwards sketched from memory with an accuracy that astonished his acquaintance, Mr. Grundy.

Before he left the metropolis, Branwell could not resist a visit to the Castle Tavern, Holborn, then kept by the veteran prize-fighter, Tom Spring, a place frequented by the principal sporting characters of the time. A gentleman named Woolven, who was present through the same curiosity which led Branwell there, noticed the young man, whose unusual flow of language and strength of memory had so attracted the attention of the spectators that they had made him umpire in some dispute arising about the dates of certain celebrated battles. Branwell and he became personal friends in after-years.’

Leyland knew Branwell Brontë well, and especially his artistic skills and ambitions as he met him in company with his artist brother. I believe he has hit the nail on the head when he talks of Branwell’s lofty ambitions as an artist. Branwell Brontë had great self-confidence in whatever he did, especially in his younger days, as we can see from the likes of his letters to William Wordsworth and Blackwood’s Magazine. To think that a lack of confidence in his own artistic ability would stop him from even sending a letter to the Royal Academy, or attempting to make his way there, surely goes against all we know of his character, just as it went against all that those who knew him best, Grundy and Leyland, knew?

We also have a letter from Charlotte Brontë dated 6 July 1835:

‘We are all about to divide, break up, separate. Emily is going to school, Branwell is going to London, and I am going to be a governess. This last determination I formed myself, knowing that I should have to take the step sometime, “and better sune as syne,” to use the Scotch proverb; and knowing well that papa would have enough to do with his limited income, should Branwell be placed at the Royal Academy, and Emily at Roe Head.’

Further evidence of this plan can be found in a July 1835 letter from the man whose job it was to finance this plan, Patrick Brontë:

‘It is my design to send my son to the Royal Academy for Artists in London, and my dear little Anne, I intend to keep at home, for another year.’

Juliet Barker and others have dismissed the testimony of Grundy and Leyland because they were written many years after the events, but if that were a valid argument in itself we would have to dismiss just about every autobiography ever written. Leyland in particular is detailed in what he writes, and he is clearly a methodical and reliable narrator. What are we to make of this Thomas Woolven who it is claimed saw Branwell Brontë in a Holborn tavern? If we look further into this, we find further points for the defence.

Attending an inn to meet famous prize fighters, bare knuckle boxers by any other name, sounds just the sort of thing Branwell Brontë would do when alone in the capital for the first time. Branwell did indeed love boxing, and was once a member of the Haworth Boxing Club. Who, though, was this mysterious Woolven? Leyland mentions him once more, later in his biography:

‘The Manchester and Leeds Railway was, at the time, in course of construction below Littleborough, passing through the picturesque and romantic vale of Todmorden. Branwell became greatly interested in the work; and as stores, and other things for the completion of the line to Hebden Bridge, were forwarded from Littleborough by canal, having been previously sent to that place from Manchester by train, he soon ingratiated himself with the boatmen, and was frequently seen in their boats. It was on one of these occasions that Mr. Woolven, previously mentioned, who was officially employed on the works, recognized at once the clever young man who had surprised the company at the ‘Castle Tavern,’ Holborn, and entered into conversation with him. These incidents led to a friendly intercourse between them, which continued for some years.’

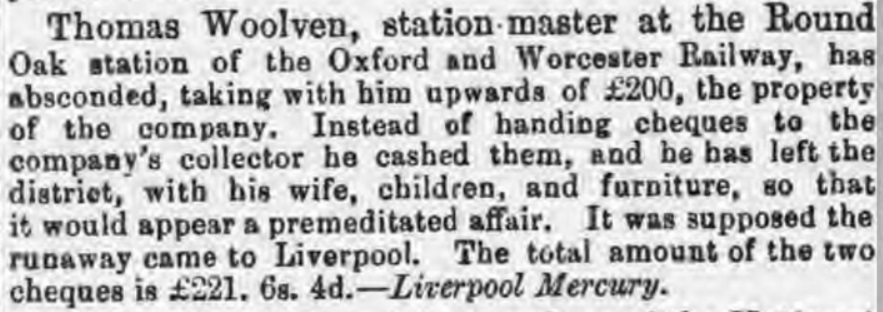

So we hear that Thomas Woolven, like Branwell, worked on the railway and became a friend of his, having first met him in London. When I delved into the newspaper archives two stories caught my eye. From 12 May 1860, reported in multiple papers including the Leeds Intelligencer we have a Thomas Woolven who is a station master who has absconded with two cheques worth more than two hundred pounds (then a huge sum).

Six years later, on 16th August 1866, we hear another, final, development via the Brighton Gazette:

‘On Friday afternoon, as the 3.30pm train from Brighton to Portsmouth was nearing the Hove station, the driver saw a man walking between the up and down lines. The whistle of the engine was immediately blown, to warn him of danger, when, instead of stepping on to the up-line he stepped on the down-line, and before the train could be stopped the engine knocked him down. The driver succeeded in pulling up the train at the Cliftonville station, and information being given there of what had occurred, search was made, and the body was found on the line shockingly mutilated and quite dead. The deceased, whose name was Thomas Woolven, was a servant of Mr Corral, coal merchant.’

Let’s imagine a scenario. Thomas Woolven has the itinerant life of a railway worker and later manager, he meets Branwell in London and again at Luddendenfoot near Halifax. Woolven is also an opportune thief, and when employed at Round Oak he steals two cheques worth many a large sum of money. He has to leave the area, but eventually finds his money is once more spent or, quite possibly, that it is too risky to catch the cheques. By 1866 his past and his demons are catching up on him so he takes his own life on what had been his life – the railway. Could it be then that Thomas Woolven, this friend of Branwell, was also involved in the theft from Luddendenfoot Station that cost Branwell Brontë his job there (simply because in his supervisory role he should have prevented it)?

What seems for sure now is that there was indeed a Thomas Woolven railway worker, and Francis Leyland’s story has some corroboration. So let’s look at the evidence for the defence: Patrick wrote to say he was sending Branwell to the Royal Academy, Charlotte wrote that Patrick was going to try to enter the Royal Academy, and Branwell wrote at the very least a draft letter to the academy. His self-confidence makes it entirely in keeping with his personality that he would at least have tried to enter the academy. His great friends Grundy and Leyland have talked with Branwell about his time in London, and a witness called Thomas Woolven, who certainly existed and whose testimony rings true, says that he saw Branwell Brontë in London.

Whether Branwell Brontë finally entered the Royal Academy admittedly has to be in grave doubt – perhaps lack of money was the deciding factor? In my mind, however, there is no doubt that Branwell Brontë did travel to London, and he did make the attempt. And I also have to say that I very much like Branwell’s portraits and think that he was a very talented artist, and no official naysaying will make me change my opinion on either of those two things.

I rest my case, and prepare for days of rest, sunshine and happiness with great company and great books, as tomorrow is my birthday. Another year, and more Brontë-related books to read and Brontë blog posts to write. Stay healthy and happy, and I hope you can join me again next Sunday for another new Brontë post.

Happy Birthday, Nick. Good detective work.

Happy Birthday and many returns!

I don’t like to disagree with yr opinions (I’m firmly with Barker), but I cannot find very much to commend Branwell’s talents as either an artist or writer. He was precociously brilliant and probably very very smart; but he shared that idiotic over confidence of some young men and which I believe characterized so much of the Victorian ‘mindset’, including Charlotte.

I wish there was a cheap edition of Charlotte’s letters available; they are the source material of so much Bronte speculation. Cheers. Mel

Thank you for the intriguing speculations. But I wonder why you chose to illustrate them with a picture of a Private View of the 1880s – many years later than the visit of Charlotte and Anne. Was it because the painter was a Yorkshireman? Or was it because one of the principal figures is Oscar Wilde and you are going to discuss his opinion that “The fiery torch lit by the Brontës has not been passed on to other hands” in a future blog? Whatever the reason – Happy Birthday.

Interesting analysis of Branwell. He created many of his own problems and ultimately succumbed to them, but I think he has been unfairly judged by history, especially because he is compared to such titans as his sisters. I hope you enjoy your birthday!

Bravo for Branwell and happy birthday to you! It is also my daughter’s birthday.

This is an excellent consideration of Branwell’s possible trip to London. Your research indicates that he did and his confidence at that time of his life is additional corroboration.