This week has seen the 171st anniversary of the completion of Shirley by Charlotte Brontë, the third of her novels to be finished and the second to be published (as her first book The Professor was only released posthumously). I love Shirley because it’s a riveting read but also because it features people and places Charlotte knew, disguised under different names, so that the protagonists Shirley and Caroline are clearly inspired by Emily and Anne Brontë. I also believe that it was an influential book, and today we’re going to look at a classic Victorian novel that I feel owes a debt of gratitude to Shirley: Elizabeth Gaskell’s North And South.

We’re all Brontë lovers, so many of us may know Elizabeth best for her biography of her friend and fellow writing great The Life Of Charlotte Brontë. She was also, however the author of eight full length novels and numerous short stories, including many dealing with horror and the supernatural. Perhaps the books that Gaskell is most famous for today are Cranford, Wives And Daughters and North And South, and the Brontë influence can clearly be seen on this latter work.

North And South was first published by Chapman And Hall in 1855, although its serialisation in Household Words magazine had begun in September 1854 – five years after the publication of Shirley. Household Words is famous today for serialising many of the novels of Charles Dickens prior to their appearance in book form, and indeed Dickens was also the owner and editor of the magazine. Perhaps for this reason, North And South is sometimes compared to Dickens’ Hard Times, as well as to Jane Austen’s Pride And Prejudice, but I think Shirley was just as important in the novel’s genesis.

North And South centres around Margaret Hale, a nineteen year old woman who has been used to a genteel and relatively wealthy existence in the South of England. After her father, a Church of England vicar, resigns his position over a matter of conscience the Hale family are forced to give up this comfortable way of living and start a new life in Milton in the industrial county of Darkshire in the north of England.

On one level Gaskell’s novel utilises elements of Austen-like romance, but it is also a moving and brilliant portrayal of the social divide in England at that time (and which still exists, to a lesser degree today). The South is affluent, bucolic, whereas the North has nouveau riche industrialists lording it over workers who exist in extreme poverty, and for whom starvation can be a real threat. Simultaneously we see the South representing the old England, languid and stuck in its ways, whereas the North is fast moving and forward looking. It is dark and dangerous in the North, but for a select few smiled on by good fortune it can also be a land of great opportunity.

Elizabeth Gaskell knew these contrasts intimately; she herself had been born Elizabeth Stevenson in Chelsea but after a tragic change in her family circumstances she moved north to be raised by her aunt in Knutsford in Cheshire. This was an affluent little town, but Elizabeth saw the darker side of northern life after she married the Unitarian minister William Gaskell and moved to Manchester amidst the beating heart of the industrial revolution.

Charlotte Brontë’s Shirley sees the titular heroine arrive in a northern mill town after coming into her inheritance, and coming into contact with the local mill owner Robert Moore and his tutor brother Louis. There are huge similarities in temperament and circumstances between Robert Moore and the mill owning John Thornton of North And South; both men seem outwardly to care purely for money and industry, paying scant regard to their workers and the appalling conditions they endure. When Thornton’s men go on strike he brings in Irish workers to take their places, whilst Robert Moore installs the latest machinery in his mill, leading to Luddite action and a pitched battle watched over by Shirley and Caroline. Illness also plays a striking part in both novels, with Caroline Helstone almost dying of tuberculosis in Shirley and in North And South we see Bessy Higgins die of byssinosis, a consumption-like disease of the lungs caused by the inhalation of cotton dust.

Industrial unrest, then, is at the heart of both novels, but surprisingly in both books the seemingly cold hearted and uncaring mill owner is also the love interest. It is testament to the power of both Elizabeth Gaskell and Charlotte Brontë as writers that we can witness the dispassionate attitude of the industrialists to their workers, and yet still be happy when their love story is fulfilled. They are fully rounded characters, and therefore like all human beings they are also complex, filled with weaknesses as well as strengths.

At the time that Elizabeth was writing North And South her friendship with Charlotte was growing, and there can be no doubt that she was a great admirer of Shirley, and that it, and its writer, was at the forefront of her mind as she wrote the saga of Margaret Hale. Both stylistically and in regards to its subject it is close to Shirley, but perhaps the greatest sign of the influence of Charlotte’s novel can be found in the names within Elizabeth Gaskell’s masterpiece.

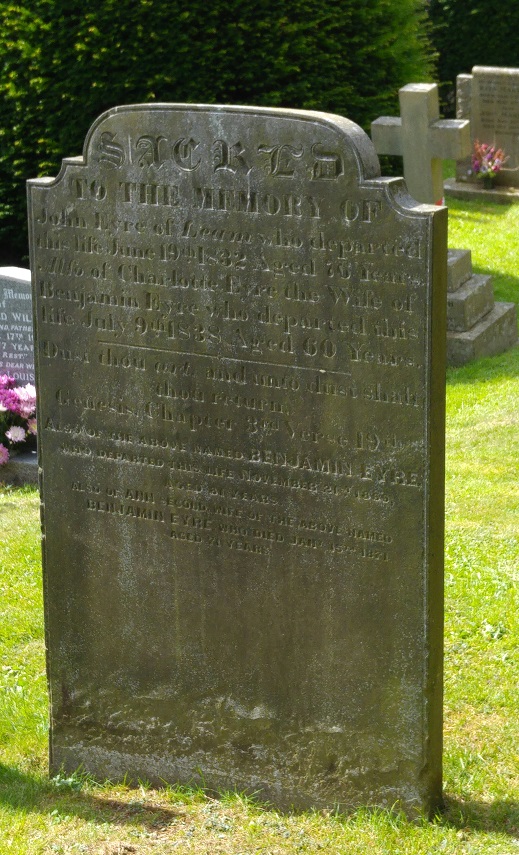

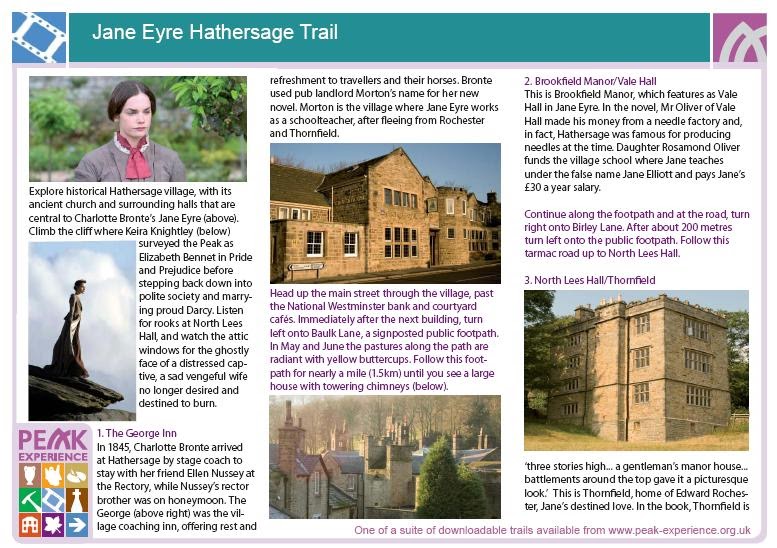

First, we have the name of the mill owner, Mr Thornton: Thornton as we know, and as Elizabeth certainly knew, was the birthplace of Charlotte Brontë. Next, we come to the village where Margaret Hale grew up before she became acquainted with Milton’s soot stained streets: Helstone. Whilst Charlotte’s second published novel is named after its character Shirley Keeldar, its true heroine (featuring across hundreds of pages before Shirley first appears) is Caroline Helstone. We also have the evidence of Margaret Hale’s godfather Mr Bell, the pen name used by Charlotte when writing Shirley.

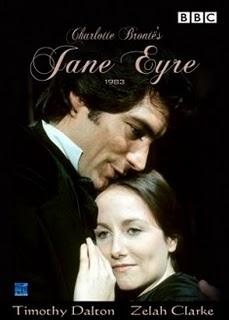

North And South is not only a brilliant book, and a searing indictment of societal inequality in the nineteenth century, it is also a tribute by Elizabeth Gaskell to Charlotte Brontë. It certainly is a brilliant book however, and deserves to be read by all who love classic fiction. There’s also an excellent BBC adaptation from 2004 starring Daniela Denby-Ashe and Richard Armitage. Now, if only we could get the BBC to dramatise Shirley, or even Anne Brontë’s Agnes Grey! Whatever book you’re reading in the coming week, enjoy it and let the turn of the pages take your troubles away. Whether you’re in the north or south, I hope to see you here again next Sunday for another new Brontë blog post.