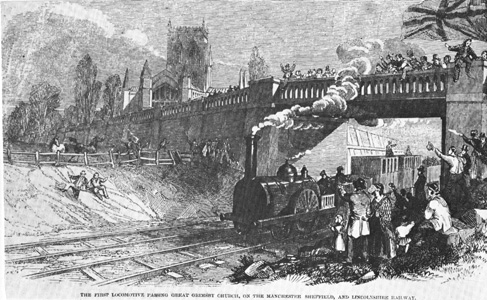

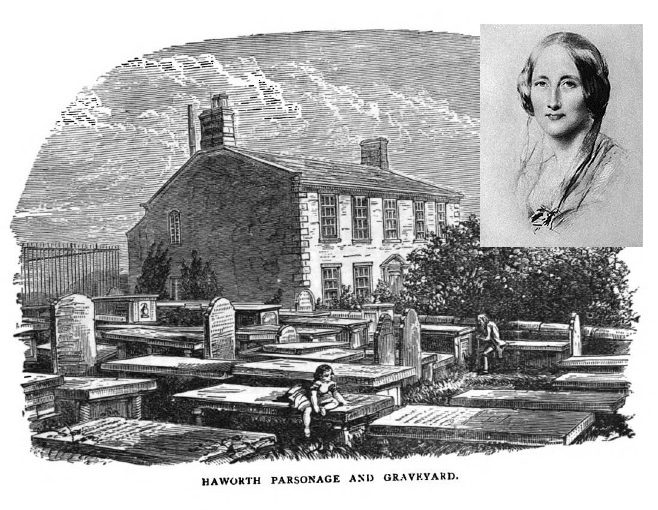

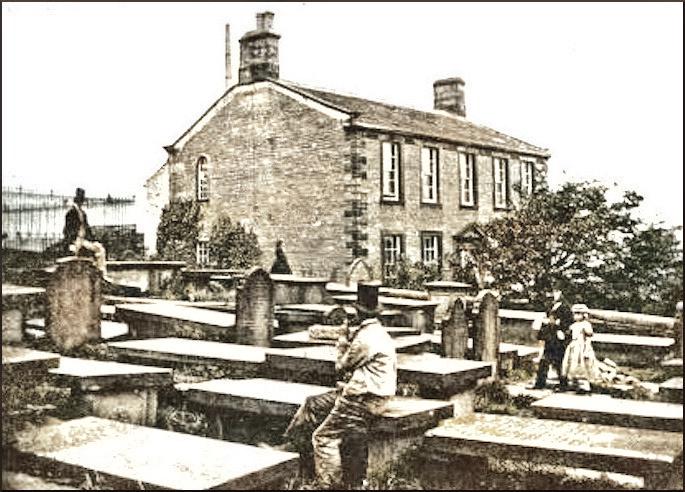

There are many ways to get to Haworth, and the Brontë Parsonage Museum within it, but surely one of the most special ways to arrive is to take a ride on an authentic steam train. The Keighley and Worth Valley Railways runs daily from Keighley, a town well known to the Brontës around five miles from their parsonage home, to Oxenhope, with a station conveniently situated at the foot of Haworth’s hill. It’s a beautiful station, and it was also used in the famous 1970 film The Railway Children.

Railway invention and expansion changed the Victorian world, and it certainly played a large part in the lives of the Brontës. Branwell Brontë found employment as a railway clerk, and as the trains opened up the country it allowed Charlotte, Anne and Emily to traverse England in an ease and style that previous generations could never have dreamed of. It also brought the Brontës money and lost the Brontës money, thanks to a man known as ‘The Railway King’: George Hudson.

Hudson was born in the North Riding of Yorkshire in 1800, and apprenticed as a draper. After marrying the owner of the business he worked for he eventually became a partner in it, leading it to become the largest single business in the city of York. In 1827 his great uncle died and left a fortune to Hudson, but it was a chance meeting in 1834 that really changed the course of his life.

In the beautiful Yorkshire seaside town of Whitby, now famous for its Dracula connection, Hudson bumped into George Stephenson, who told him of his plans to create a railway that would run from London to the north of England. Hudson became a business partner of Stephenson, and then a railway pioneer in his own right, founding the York and North Midland Railway and opening lines across the north of England, including the line that carried Charlotte Bronte, along with her friend Ellen Nussey, to her first view of the sea at Burlington.

Hudson served as Lord Mayor of York on three occasions, and also became a long serving Tory MP for Sunderland. He was by this time the head of a sprawling business empire encompassing a large number of individual railway companies, but it seemed that everything he touched turned to gold, which was very attractive to investors – investors such as the Brontë sisters.

The railway revolution in the 1830s and 1840s was as dramatic and transformational at the time as the internet and social media revolution is today, and lines were being opened at a furious pace. With a rapid rise in passenger numbers year upon year, as well as in its freight operations, there were large potential profits to be made. The Brontës were not a particularly wealthy family, but in 1842 their monetary position changed considerably when Anne, Emily and Charlotte (along with their Penzance cousin Eliza Kingston) were each left around £300 each, the equivalent of around six years wage for a governess. This money would eventually help pay for the publication of some of the Brontë books we love today, but in 1842 the sisters had to decide how to save or invest it. The decision was taken to let Emily manage their joint funds, and she invested it in the then booming railway stock of George Hudson’s companies.

From surviving fragments of Emily Brontë’s account book we can see that she took this duty seriously, and that she was often to be found re-investing their profits and buying more railway shares. In 1845 Emily records that she has made a ‘speculation’, but it must have been a lucrative one for her accounts for 1846 show that she had an income of £305 in that year, compared to £110 in the previous one.

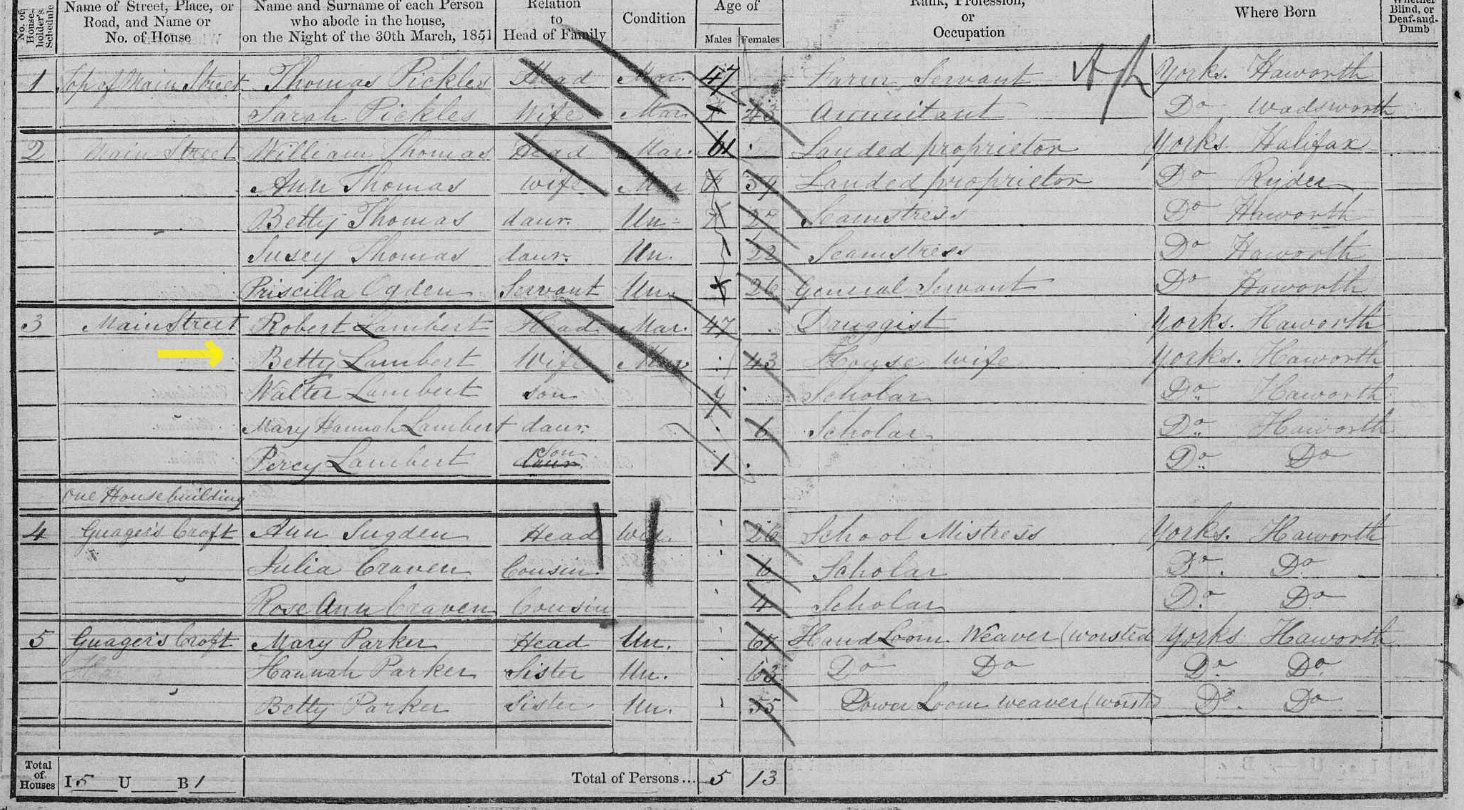

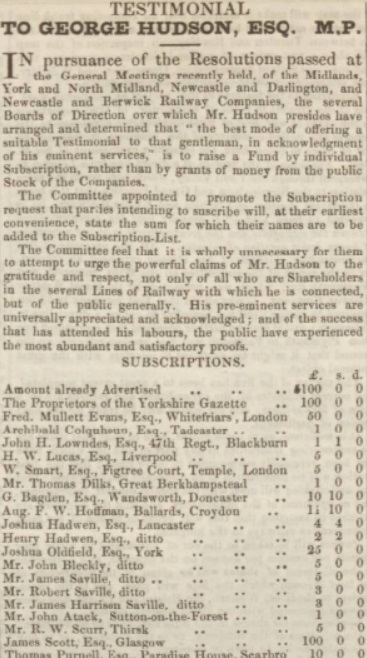

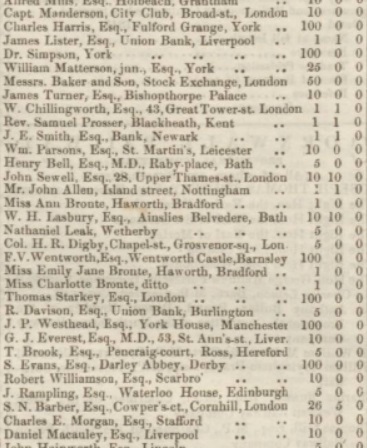

Perhaps the success of this speculation and others was the reason that the Brontës contributed to a subscription being made for George Hudson, as shown in an article within the Yorkshire Gazette on 27th September 1845. The newspaper urges people who have profited from Hudson’s railway expansion to pledge money to be given to the man himself, and amidst a list of often exalted people who have already pledge to do so can be found ‘Miss Ann Brontë’, ‘Miss Emily Jane Brontë’ and ‘Miss Charlotte Brontë’ of Haworth, Bradford, who have all given a pound each.

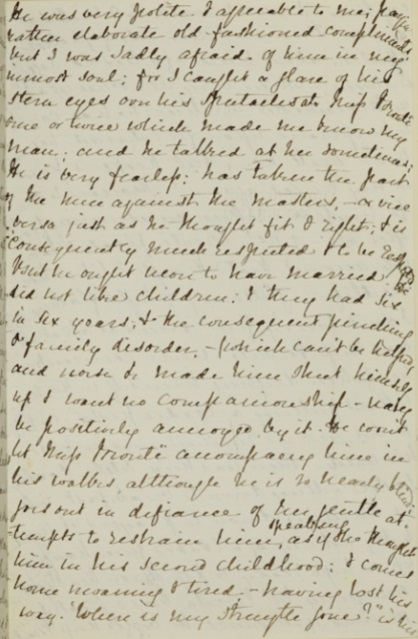

A letter sent by Charlotte Brontë to Margaret Wooler on 30th January 1846, however, indicates that she was concerned by the bullish nature of Emily’s investments:

‘I thought you would wonder how we were getting on, when you heard of the railway panic, and you may be sure that I am very glad to be able to answer your kind inquiries by an assurance that our small capital is as yet undiminished. The York and Midland is, as you say, a very good line; yet, I confess to you, I should wish, for my own part, to be wise in time. I cannot think that even the very best lines will continue for many years at their present premiums; and I have been most anxious for us to sell our shares ere it be too late, and to secure the proceeds in some safer, if, for the present, less profitable investment. I cannot, however, persuade my sisters to regard the affair precisely from my point of view; and I feel as if I would rather run the risk of loss than hurt Emily’s feelings by acting in direct opposition to her opinion. She managed in a most handsome and able manner for me, when I was in Brussels, and prevented by distance from looking after my own interests; therefore, I will let her manage still, and take the consequences. Disinterested and energetic she certainly is; and if she be not quite so tractable or open to conviction as I could wish, I must remember perfection is not the lot of humanity; and as long as we can regard those we love and to whom we are closely allied, with profound and never-shaken esteem, it is a small thing that they should vex us occasionally by what appear to us unreasonable and headstrong notions. You, my dear Miss Wooler, know full as well as I do, the value of sisters’ affection to each other; there is nothing like it in this world, I believe, when they are nearly equal in age, and similar in education, tastes, and sentiments.’

As we can see, by 1846 there are already hints that the railway boom is over, and many small lines and businesses had already closed or been taken over by bigger competitors. These fledgling railways were a series of highly competitive franchises, and yet Hudson still seemed to outperform his business rivals. His tactics sound all too familiar in today’s world, as he aimed to maximise profits for his shareholders by cutting his workforce to a minimum and cutting back on safety measures, often with fatal consequences for employees and passengers alike.

By 1845, he was one of the wealthiest and most powerful industrialists in England, with a newspaper praising his ‘penetration more than human, and a genius comprehensive, lofty and intuitive.’ It also, however, went on to paint a less than flattering picture of his physical appearance, noting a sinister leer of the eyes, an ungainly frame, a short bull-neck and an unharmonious voice.

The railway shares of the Brontës continued to prosper during the lifetimes of Anne and Emily, the driving force, behind the investment but all was not well in the world of George Hudson and the Midland Railway. We get a clue to this in a letter sent by Charlotte Brontë to George Smith on this very day in 1849:

‘My shares are in the York & North Midland Railway. It was one of Mr. Hudson’s pet lines and the full benefit of his peculiar management – or mis-management. The original price of shares in the railway was £50; at one time they rose to 120; and for some years gave a dividend of 10 percent; they are now down at 20, and it is doubtful whether any dividend will be declared this half-year.’

As Charlotte had predicted, the shares had soon become worthless, and George Hudson himself received a fall from grace as meteoric as his rise had been. It was eventually discovered that Hudson and his railways were operating via a system of smoke and mirrors, his profits having been grossly over-exaggerated and with shareholders such as Charlotte, Emily and Anne paid out of the company’s capital rather than the money they were earning.

Hudson lost his hold on his business empire and it was found that his debts ran into the hundreds of thousands of pounds (tens of millions of pounds today). After losing his seat as Sunderland’s MP in 1865 he lost immunity from imprisonment and was incarcerated in York gaol. A local colliery owner paid off enough of Hudson’s debts for him to be released on remand, after which he promptly fled the country to live in France. In 1870 a new law put an end to imprisonment for debts, and Hudson returned from his exile, but he died in London in 1871. The Railway King was dead. His machinations had ruined many of his investors, and Charlotte Brontë lost much of her savings including, it’s believed, an initial payment of £500 that she received for Jane Eyre. Nonetheless, he had left a lasting legacy, and his stations and railway lines are still a central part of our transport infrastructure today. Huge crowds turned out at George Hudson’s funeral, and to see his coffin loaded onto a train that would carry him from London to York – the station he had had built. Few people can encapsulate the boom and bust of Victorian railway expansion more than George Hudson, but he changed the Brontës lives and the world that we live in today.

Here’s a safer investment that I can always recommend: a good book, and if you stay in your armchair you don’t even need to wear a mask to read it. I will see you again next Sunday for another new Brontë blog post.