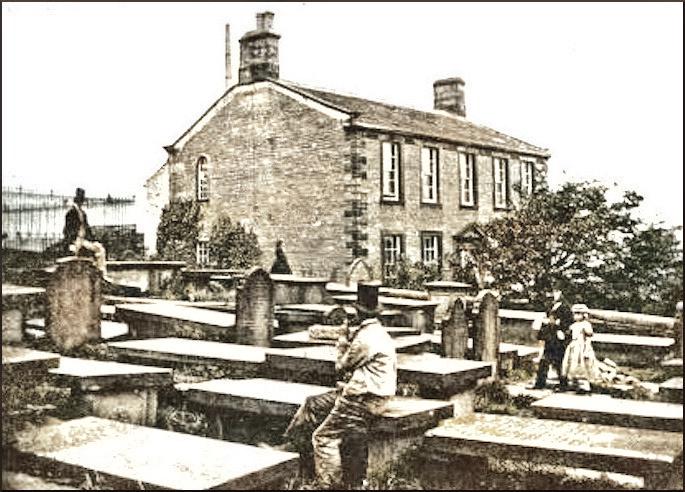

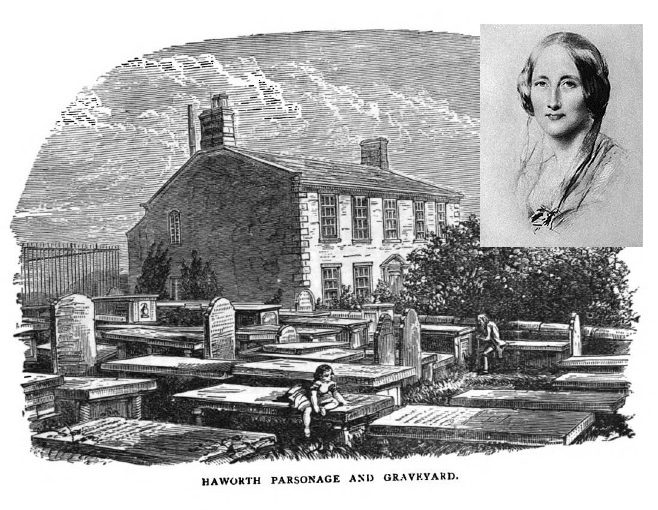

This year has been a strange one in many ways, and one result is that not as many people have been able to visit the Brontë Parsonage Museum in Haworth as in previous years. Whenever we visit however it still thrills the soul; we can almost step back in time and imagine what these same cobbled streets would have seen at the time that the Brontës lived in Haworth. If we could have stepped back to this week 167 years ago we would have seen a very special visitor climb out of a carriage at Main Street’s summit, for it was in this week in 1853 that Elizabeth Gaskell began a six day visit to her friend Charlotte Brontë. In today’s Brontë blog post we’re going to look at Elizabeth Gaskell in Haworth, and at what she thought of the people who lived there.

Charlotte was a great fan of Elizabeth’s writing even before they met in person, an event which took place in late August 1850 at Briery Close, one of the Lake District properties belonging to Sir James Kay-Shuttleworth and his wife. Charlotte wrote to Ellen Nussey describing her first impressions of her fellow author:

‘Fortunately there was Mrs. Gaskell (the authoress of “Mary Barton”) who came to the Briery the day after me – I was truly glad of her companionship. She is a woman of the most genuine talent – of cheerful, pleasing and cordial manners, and – I believe – of a kind and good heart.”

We have a rather more fulsome description of Charlotte’s appearance and character from Elizabeth Gaskell’s point of view after this initial meeting, thanks to two remarkable letters that Elizabeth wrote shortly after their meeting. To Catherine Winkworth she wrote:

‘She is, (as she calls herself) undeveloped; thin and more than half a head shorter than I, soft brown hair, not so dark as mine; eyes (very good and expressive looking straight & open at you) of the same colour, a reddish face; large mouth & many teeth gone; altogether plain; the forehead square, broad and rather overhanging. She has a very sweet voice, rather hesitates in choosing her expressions, but when chosen they seem without an effort, admirable and just befitting the occasion. There is nothing overstrained but perfectly simple… Such a life as Miss B.’s I never heard of before.’

To a friend and fellow writer named Charlotte Froude, Elizabeth Gaskell wrote:

‘Miss Brontë I like. Her faults are the faults of the peculiar circumstances in which she has been placed; and she possesses a charming union of simplicity and power; and a strong feeling of responsibility for the Gift, which she has given her. She is very little & very plain. Her stunted person she ascribes to the scanty supply of food she had as a growing girl, when at that school of the Daughters of the Clergy… She is truth itself – and of a very noble sterling nature, – which has never been called out by anything kind or genial… She is very silent & very shy; and when she speaks chiefly remarkable for the admirable use she makes of simple words, & the way in which she makes language express her ideas. She and I quarrelled and differed about almost every thing, – she calls me a democrat, & can not bear Tennyson – but we like each other heartily I think & I hope we shall ripen into friends.’

These remarkable letters show a kindred spirit between Charlotte Brontë and Elizabeth Gaskell; Elizabeth too was very forthright in her opinions, and would always be at pains to describe a person as they really were, both good and bad. From this initial encounter friendship did indeed ripen, and Charlotte visited Elizabeth in Manchester on a number of occasions after this.

By June 1853 Elizabeth Gaskell was preparing to make her first visit to Haworth, but an illness of Charlotte’s meant that it was delayed until September. Unfortunately we only have a small fragment of a letter from Charlotte to Elizabeth describing the aftermath of the visit:

‘After you left, the house felt very much as if the shutters had been suddenly closed and the blinds let down. One was sensible during the remainder of the day of a depressing silence, shadow, loss and want. However, if the going away was sad, the stay was very pleasant and did permanent good. Papa, I am sure, derived real benefit from your visit; he has been better ever since.’

We see, then, that Patrick Brontë enjoyed the company of Elizabeth Gaskell, but she seems to have been less enamoured of him, writing of him to John Forster:

‘He was very polite & agreeable to me; paying rather elaborate old-fashioned compliments, but I was sadly afraid of him in my inmost soul; for I caught a glare of his stern eyes over his spectacles at Miss Brontë once or twice which made me know my man.’

This seems a rather harsh snap judgement of Patrick. He used old-fashioned compliments because he was an old man, by then in his mid-seventies and a man very much of the eighteenth rather than nineteenth century. He ‘glared’ because he was once again nearly blind, and had trouble seeing what was in front of him. This harsh view endured in Elizabeth Gaskell’s mind and helped produce the unfair portrait of him in her later biography of Charlotte Brontë, particularly as she had by then also heard harsh words against him spoken by a still bitter Martha Wright, a servant he’d had to dismiss.

From The Life Of Charlotte Brontë we can also discern what Elizabeth Gaskell thought about Haworth and the people who lived there:

‘For a right understanding of the life of my dear friend, Charlotte Brontë, it appears to me more necessary in her case than in most others, that the reader should be made acquainted with the peculiar forms of population and society amidst which her earliest years were passed, and from which both her own and her sisters’ first impressions of human life must have been received. I shall endeavour, therefore, before proceeding further with my work, to present some idea of the character of the people of Haworth, and the surrounding districts.

Even an inhabitant of the neighbouring county of Lancaster is struck by the peculiar force of character which the Yorkshiremen display. This makes them interesting as a race; while, at the same time, as individuals, the remarkable degree of self-sufficiency they possess gives them an air of independence rather apt to repel a stranger. I use this expression “self-sufficiency” in the largest sense. Conscious of the strong sagacity and the dogged power of will which seem almost the birthright of the natives of the West Riding, each man relies upon himself, and seeks no help at the hands of his neighbour. From rarely requiring the assistance of others, he comes to doubt the power of bestowing it: from the general success of his efforts, he grows to depend upon them, and to over-esteem his own energy and power. He belongs to that keen, yet short-sighted class, who consider suspicion of all whose honesty is not proved as a sign of wisdom. The practical qualities of a man are held in great respect; but the want of faith in strangers and untried modes of action, extends itself even to the manner in which the virtues are regarded; and if they produce no immediate and tangible result, they are rather put aside as unfit for this busy, striving world; especially if they are more of a passive than an active character. The affections are strong and their foundations lie deep: but they are not – such affections seldom are – wide-spreading; nor do they show themselves on the surface. Indeed, there is little display of any of the amenities of life among this wild, rough population. Their accost is curt; their accent and tone of speech blunt and harsh. Something of this may, probably, be attributed to the freedom of mountain air and of isolated hill-side life; something be derived from their rough Norse ancestry. They have a quick perception of character, and a keen sense of humour; the dwellers among them must be prepared for certain uncomplimentary, though most likely true, observations, pithily expressed. Their feelings are not easily roused, but their duration is lasting. Hence there is much close friendship and faithful service; and for a correct exemplification of the form in which the latter frequently appears, I need only refer the reader of “Wuthering Heights” to the character of “Joseph.”

From the same cause come also enduring grudges, in some cases amounting to hatred, which occasionally has been bequeathed from generation to generation. I remember Miss Brontë once telling me that it was a saying round about Haworth, “Keep a stone in thy pocket seven year; turn it, and keep it seven year longer, that it may be ever ready to thine hand when thine enemy draws near.”

The West Riding men are sleuth-hounds in pursuit of money. Miss Brontë related to my husband a curious instance illustrative of this eager desire for riches. A man that she knew, who was a small manufacturer, had engaged in many local speculations which had always turned out well, and thereby rendered him a person of some wealth. He was rather past middle age, when he bethought him of insuring his life; and he had only just taken out his policy, when he fell ill of an acute disease which was certain to end fatally in a very few days. The doctor, half-hesitatingly, revealed to him his hopeless state. “By jingo!” cried he, rousing up at once into the old energy, “I shall do the insurance company! I always was a lucky fellow!”‘

These men are keen and shrewd; faithful and persevering in following out a good purpose, fell in tracking an evil one. They are not emotional; they are not easily made into either friends or enemies; but once lovers or haters, it is difficult to change their feeling. They are a powerful race both in mind and body, both for good and for evil.’

One thing for certain is that the week that Elizabeth Gaskell spent in Haworth was an important one for English literature, it cemented her friendship with Charlotte Brontë and it paved the way for her biography of the woman she had known and come to love. It’s not a flawless biography, such a book has never been written after all, but it is an essential read for it is beautifully written, and by a fellow genius who knew and understood Charlotte better than almost anyone else.

Elizabeth Gaskell spoke and wrote with unflinching honesty and openness, just as Charlotte did, but her aim was a simple one, as she reveals at the incredibly moving close of her biography:

‘I have little more to say. If my readers find that I have not said enough, I have said too much. I cannot measure or judge a character such as hers. I cannot map out vices, and virtues, and debatable land… But I turn from the critical, unsympathetic public, – inclined to judge harshly because they have only seen superficially and not thought deeply. I appeal to that larger and more solemn public, who know how to look with tender humility at faults and errors; how to admire generously extraordinary genius, and how to reverence with warm, full hearts all noble virtue. To that Public I commit the memory of Charlotte Brontë.’

I must go now. As a man born in the West Riding of Yorkshire myself I’m off to turn the stone in my pocket. Stay safe and happy, and I will see you next week for another new Brontë blog post.

Fascinating. Thank you.

Eliz Gaskell in Haworth … excellent. Love reading these wonderful insights, thank you. To fall back 167 years and read how people change and yet remain the same is a common reminder to us all to study history (in all forms) … it always repeats itself.