A lot of us have had a lot of extra time on our hands this year, for better or worse. It’s been an anxious year at times, of course, but it’s also provided the opportunity for many to learn new skills or spend time doing the things they love – like reading a good book. It has also provided opportunities for reflection, so it may be that you’ve started a journal or diary. If so, then you’re in good company for this week was the 186th anniversary of the first diary paper written by Emily and Anne Brontë, so in today’s post we’re going to look at it and how it came to be discovered.

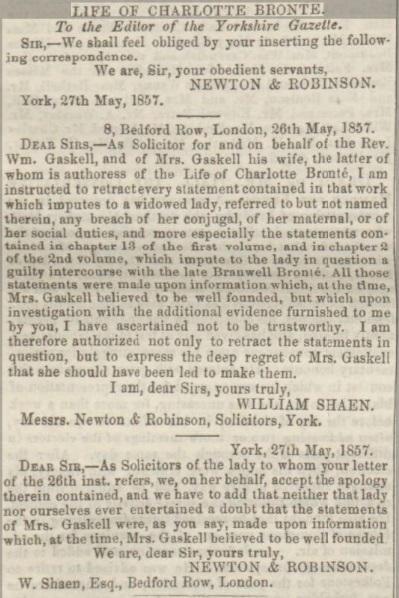

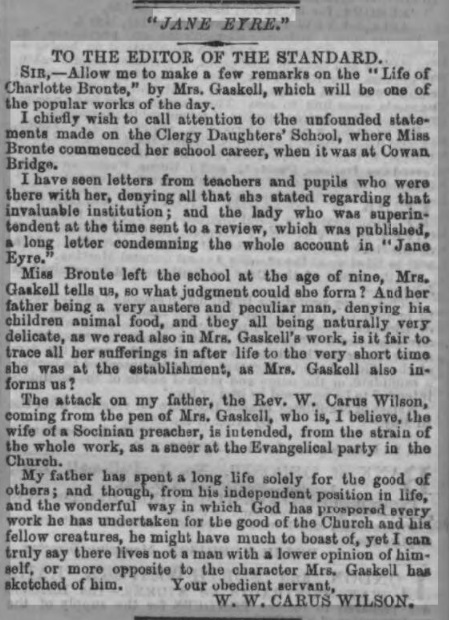

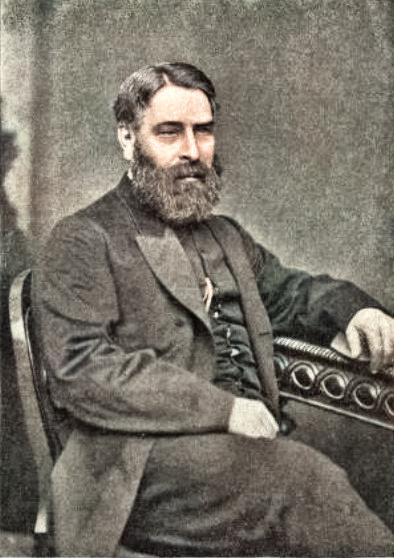

After the tragic early death of Charlotte Brontë in 1855 the majority of her possessions went to her husband Arthur Bell Nicholls, although some items were left to her friend and faithful parsonage servant Martha Brown. Without doubt Arthur continued to love Charlotte until the end of his days, although he did later marry his cousin Mary Bell after returning to Ireland (Mary’s father was a priest, so Arthur had married both Currer Bell and the daughter of Curate Bell). Charlotte’s legacy was painful to look at, and for that reason many of Charlotte’s items went untouched by Arthur for many years. It was forty years after Charlotte’s passing that Arthur took a look at one particular item and made an incredible discovery.

The item was a plain tin cash box which Branwell Brontë had at one point gifted to his sister Emily. Emily Brontë had used it as a sewing box, so upon opening it Arthur found a collection of bobbins, needles, thimbles and thread. Turning it over in his hands however he found something else, a hidden compartment secreted at the base of the box.

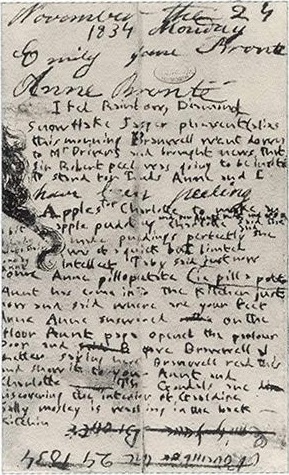

Opening this compartment, Arthur found something completely unexpected, and completely remarkable. It held a collection of tiny folded pieces of paper, placed there by Emily before her death in 1848. These papers were what we now call the ‘diary papers’ written by Emily and Anne Brontë in the years 1834, 1837, 1841 and 1845 and they give a remarkable insight into life in the Brontë household, and in their lives, at these times. The first diary paper was written jointly by Emily and Anne on 24th November 1834, and is reproduced in full below:

“November the 24, 1834 Monday, Emily Jane Brontë, Anne Brontë,

I fed Rainbow, Diamond, Snowflake, Jasper, pheasant this morning. Branwell went down to Mr Drivers and brought news that Sir Robert Peel was going to stand for Leeds. Anne and I have been peeling apples for Charlotte to make an apple pudding and for Aunt’s nuts and apples. Charlotte said she made puddings perfectly and she was of a quick but limited intellect. Tabby said just now come Anne pilloputate (ie pill a potato). Aunt has come into the kitchen just now and said, ‘where are your feet Anne?’ Anne answered, ‘on the floor Aunt’. Papa opened the parlour door and gave Branwell a letter saying, ‘here Branwell read this and show it to your Aunt and Charlotte’. The Gondals are discovering the interior of Gaaldine, Sally Mosley is washing in the back kitchen.

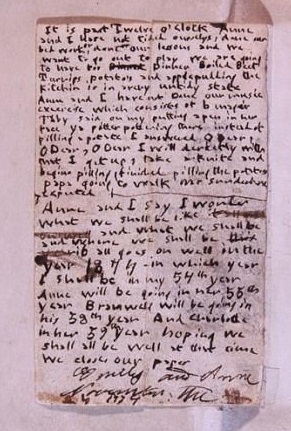

It is past twelve o’clock Anne and I have not tidied ourselves, done our bed work or done our lessons and we want to go out to play. We are going to have for dinner boiled beef, turnips, potatoes and apple pudding; the kitchen is in a very untidy state. Anne and I have not done our music exercise which consists of b major. Tabby said, on my putting a pen in her face, ‘ya pitter pottering there instead of pilling a potate’, I answered, ‘oh dear, oh dear, oh dear, I will directly’. With that I get up, take a knife and begin pilling (finished pilling the potatoes). Papa going to walk. Mr Sunderland expected.

Anne and I say I wonder what we shall be like and what we shall be and where we shall be if all goes on well in the year 1874 – in which year I shall be in my 57th year, Anne will be going in her 55th year, Branwell will be going in his 58th year, and Charlotte in her 59th year; hoping we shall all be well at that time, we close our paper.

Emily and Anne, November the 24 1834”

In its mundanity is its brilliance. It shows teenage girls in 1834 (Anne and Emily were 14 and 16 at the time) being much like teenagers today – they haven’t done their homework, haven’t tidied their rooms and want to go out to play. The handwriting is messy and punctuation and spelling an afterthought, typical of Emily at this time but she would grow up to be one of the greatest, some might say the greatest, novelist of all time. Emily also loved to draw and doodle, as we see in subsequent diary papers, but in the 1834 entry it is Anne who has drawn long flowing hair down the left hand side of the front page.

This is also a very moving piece of writing, particulary as Emily and Anne wonder what they will all be doing in 1874. Arthur first saw this diary paper 21 years after that date, so he knew as we do that by 1874 they were all, alas, long dead.

It was an incredible yet chance discovery that has given us lots of valuable and fascinating information on the Brontës. Above all, it shows them as humans like you and I, rather than the towering genii they are often encountered as. What a lucky discovery, and who knows what other discoveries may yet be made?

Perhaps today could be a good day to start your own journal, after all future generations are sure to be fascinated, and possibly bemused, by how we live our lives today? I hope you can join me again next Sunday for another new Brontë blog post; hoping we shall all be well at that time, I close my post.