Halloween comes but once a year, but that’s why I like to make it last all weekend, meaning that today it’s time for this year’s Brontë Halloween blog post! In previous years we’ve looked at the Long Island staircase said to be haunted by Anne Brontë, at the Gytrash of Ponden Hall, and at the ghost of Mrs Baines which haunted Penzance at the time that the Brontës’ mother Maria and their Aunt Branwell lived there. Today we’re going to look at ghosts in the writing of Charlotte Brontë, and a spooky report of Charlotte being a ghost herself.

Emily’s Wuthering Heights, of course, is a book full of superstition and gothic tones, and yet it is Charlotte Brontë who most consistently wrote about the supernatural and otherworldly. Her unfinished book Willie Ellin sees an unnamed spirit taking up residence in the human world, and even when a teacher at Roe Head school it seemed that Charlotte was experiencing phenomena that can’t easily be explained away, as we see from this excerpt from her journal:

‘The toil of the day, succeeded by this moment of divine leisure, had acted on me like opium & was coiling about me a disturbed but fascinating spell, such as I never felt before. What I imagined grew morbidly vivid. I remember I quite seemed to see, with my bodily eyes, a lady standing in the hall of a gentleman’s house, as if waiting for some one.’

Could this vision have been waiting in the hall of a gentleman’s house, waiting for Charlotte to take up her pen ten years later and write her story in Jane Eyre? This novel too is full of hauntings, of past spectres being made all too real, and it contains one of the most famous ghost scenes of them all as the young Jane is banished to the red-room:

‘This room was chill, because it seldom had a fire; it was silent, because remote from the nursery and kitchen; solemn, because it was known to be so seldom entered. The house-maid alone came here on Saturdays, to wipe from the mirrors and the furniture a week’s quiet dust: and Mrs. Reed herself, at far intervals, visited it to review the contents of a certain secret drawer in the wardrobe, where were stored divers parchments, her jewel-casket, and a miniature of her deceased husband; and in those last words lies the secret of the red-room—the spell which kept it so lonely in spite of its grandeur.

Mr. Reed had been dead nine years: it was in this chamber he breathed his last; here he lay in state; hence his coffin was borne by the undertaker’s men; and, since that day, a sense of dreary consecration had guarded it from frequent intrusion.

My seat, to which Bessie and the bitter Miss Abbot had left me riveted, was a low ottoman near the marble chimney-piece; the bed rose before me; to my right hand there was the high, dark wardrobe, with subdued, broken reflections varying the gloss of its panels; to my left were the muffled windows; a great looking-glass between them repeated the vacant majesty of the bed and room. I was not quite sure whether they had locked the door; and when I dared move, I got up and went to see. Alas! yes: no jail was ever more secure. Returning, I had to cross before the looking-glass; my fascinated glance involuntarily explored the depth it revealed. All looked colder and darker in that visionary hollow than in reality: and the strange little figure there gazing at me, with a white face and arms specking the gloom, and glittering eyes of fear moving where all else was still, had the effect of a real spirit: I thought it like one of the tiny phantoms, half fairy, half imp, Bessie’s evening stories represented as coming out of lone, ferny dells in moors, and appearing before the eyes of belated travellers. I returned to my stool.

Superstition was with me at that moment; but it was not yet her hour for complete victory: my blood was still warm; the mood of the revolted slave was still bracing me with its bitter vigour; I had to stem a rapid rush of retrospective thought before I quailed to the dismal present… Shaking my hair from my eyes, I lifted my head and tried to look boldly round the dark room; at this moment a light gleamed on the wall. Was it, I asked myself, a ray from the moon penetrating some aperture in the blind? No; moonlight was still, and this stirred; while I gazed, it glided up to the ceiling and quivered over my head. I can now conjecture readily that this streak of light was, in all likelihood, a gleam from a lantern carried by some one across the lawn: but then, prepared as my mind was for horror, shaken as my nerves were by agitation, I thought the swift darting beam was a herald of some coming vision from another world. My heart beat thick, my head grew hot; a sound filled my ears, which I deemed the rushing of wings; something seemed near me; I was oppressed, suffocated: endurance broke down; I rushed to the door and shook the lock in desperate effort.’

The heroine of Villette, Lucy Snowe, also finds herself beguiled and besieged by dread of the supernatural, thanks to the recurring presence of a ghost nun:

The Brontës had been brought up on ghostly folkore and tales of the supernatural, thanks to the Pennine tales of their loyal servant Tabby Aykroyd and the Cornish tales regaled by their Aunt Branwell. It’s easy to imagine them telling each other spooky stories by candlelight on All Hallow’s Eve, but perhaps more surprising were the stories that circulated in the 1920s of Charlotte Brontë herself appearing as a ghost!

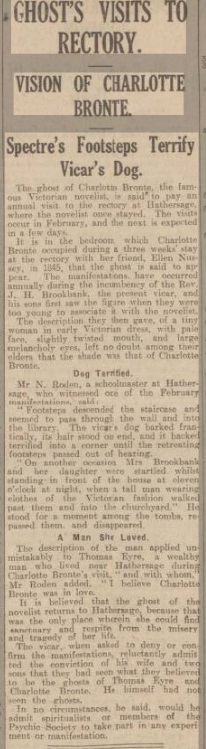

It is reported here in February 1927 that Charlotte’s ghost has been appearing on an annual basis at the beautiful Hathersage Parsonage where she stayed with Ellen Nussey in 1845. The incumbent vicar’s children often see her ghost, and her appearance is said to terrify the dog. The article also conjectures that her phantom returns to this spot because she was in love with the man who lived there, Reverend Henry Nussey whose proposal she rejected and who at least partially inspired St. John Rivers in Jane Eyre, and because she had found calm at Hathersage in contrast to the misery of Haworth. The article also points out that the ghost of Thomas Eyre, who had lived at nearby North Lees Hall, also haunted the building and that the Psychic Society had offered to help investigate the matter, but their request was not being entertained.

A month later, however, Hathersage’s vicar the Reverend J. H. Brookbank took to the press to deny these claims, saying that the idea that he and his family had seen Charlotte’s ghost was absurd – but perhaps it’s telling that there was no comment from the family dog!

We’ve had a little bit of Halloween fun today, and I think we could all do with that as another lockdown looms. Once again, Brontë books will prove invaluable in the weeks ahead, so please join me next Sunday for another new post. Next Sunday will be the special one that I hinted at in last week’s post, so I hope you can join me for it. Stay safe and if you have a terrified pet today don’t panic, it’s probably just Charlotte Brontë popping by to say hello.

Thank you for this entertaining post. Is it possible that Charlotte had ‘the gift’ of second sight which some people do believe. An interesting point is in Sharon Wright’s book about Maria Bronte of the 5 year old Charlotte seeing ‘a fairy’ by baby Anne’s cradle. Charlotte experienced such personal loss as a child as well as later it would be no surprise that she was very sensitive to the spirit world

Just wondering why Charlotte rejected Henry Nussey’s proposal if she was in love with him.