Other than the Brontë novels themselves, it’s hard to beat a good Brontë biography. Contrary to popular belief, Elizabeth Gaskell’s The Life Of Charlotte Brontë wasn’t the first Brontë biography (that was by the mysterious W. P. P. and you can read about it here) but it was certainly the first officially sanctioned biography, and it helped to cement Charlotte Brontë’s reputation which endures to this day. Gaskell herself died on this week in 1865, so in today’s work we will take a look at the torrid history of her Brontë biography, and at why she wished she’d never written it.

The first thing we should say is that The Life Of Charlotte Brontë was a huge success upon its publication by Smith, Elder & Co. in March 1857. This success, sales wise and acclaim wise, has continued: Woman At Home magazine in 1896 said, ‘in the whole of English literature there is no book that can compare in widespread interest with The Life Of Charlotte Brontë by Mrs. Gaskell’, and in 2017 it featured in The Guardian’s list of the hundred best non-fiction books of all time.

By 16th June 1857 however, just three months after its publication, Gaskell wrote to Ellen Nussey (Charlotte’s great friend who had been the major source for the biography): ‘I am in the Hornet’s nest with a vengeance… I have cried more since I came home than I ever did in the same space of time before; and never needed kind words so much – & no one gives me them.’

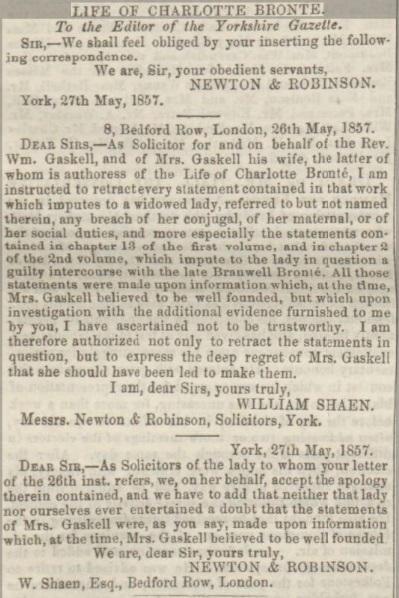

What had happened? By May 1857 the first edition had completely sold out and a second edition had been released, but a month later the book was removed from sale, and we get a clue why in this edition of the Yorkshire Gazette dated 30th May 1857 (and which appeared in other papers across the country:

A certain lady, carefully not mentioned by name in either The Life Of Charlotte Brontë nor in these letters has threatened to sue Gaskell and her publishers after the book ‘impute to the lady in question a guilty intercourse with the late Branwell Brontë.’

The passage of time, of course, allows us to identify the lady as the former Lydia Robinson of Thorp Green Hall, by 1857 the rather grander Lady Scott. It is interesting to note that the solicitor acting on behalf of Lady Scott was a W. Shaen of Newton & Robinson solicitors of London, and the person acting on behalf of the Gaskells was William Shaen of Newton & Robinson solicitors of York. At least somebody must have done well out of the matter, as they wrote legal letters to themselves. It would have been interesting to see what would have happened if it had ended up in court.

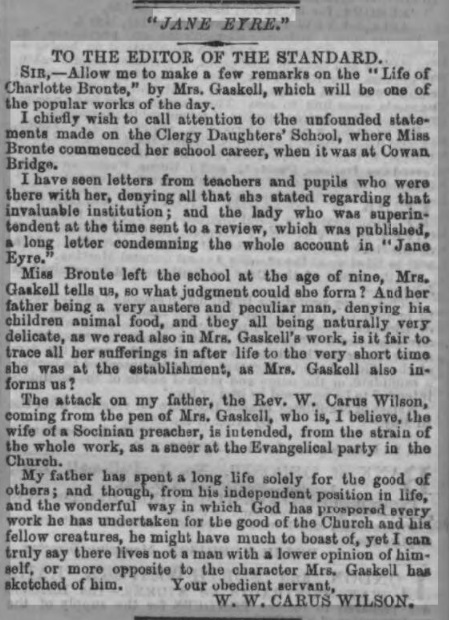

Gaskell was forced to apologise and rewrite the chapters involving Branwell and Lydia Robinson and the injunction was lifted, but her troubles didn’t end there. On 24th April 1857, W. W. Carus Wilson, having read The Life Of Charlotte Brontë, wrote to The London Evening Standard:

The letter writer is the son of the Reverend William Carus Wilson, founder of the Clergy Daughter’s School at Cowan Bridge, who insisted that his father ‘has spent a life solely for the good of others.’

This seems in rather bad taste when you consider that Maria and Elizabeth Brontë were just two of the many children who had died in (or after being sent home from) Wilson’s harsh schools – with large numbers of deaths recorded both in the time of the Brontës and in succeeding decades. Wilson junior attributes the stories within the biography to Elizabeth Gaskell’s dislike of the ‘evangelical’ wing of the church. The Wilson family and friends launched a prolonged campaign against the book and its author, and they too threatened legal action meaning that once again the book had to be re-written. Thankfully no amount of threatening letters and legal action can remove the character of Mr. Brocklehurst from Jane Eyre nor will it stop readers from knowing that, as Charlotte herself had asserted, that this was a facsimile portrait of the cruel Carus Wilson.

Sources closer to the Brontë family also found cause to complain to Elizabeth Gaskell. Patrick Brontë, the man who had originally commissioned Gaskell to write the biography of his daughter, was unhappy at his portrayal within it, and especially the statement (which we know to be untrue) that he had denied his children meat. It was for this reason that Patrick spoke to The Daily News England in August 1857, who reported:

‘With regard to the statement that Mr Brontë, in his desire to bring up his children simply and heartily, refused to permit them to eat flesh meat he asserts that Nancy Garrs alleges that the children had meat daily, and as much of the food as they chose. The early article from which they were restrained was butter, but its want was compensated for by what is known in Yorkshire as ‘spice-cake,’ a description of bread which is the staple food at Christmas for all meals but dinner.

“I did not know that I had an enemy in the world, much less one who would traduce me before my death. Everything in that book [The Life Of Charlotte Brontë] which relates to my conduct to my family is either false or distorted. I never did commit such acts as are ascribed to me. I stated this in a letter which I sent to Mrs Gaskell, requesting her at the same time to cancel the false statements made about me in her next edition of her book. To this I received no answer than that Mrs Gaskell was unwell, and unable to write.”’

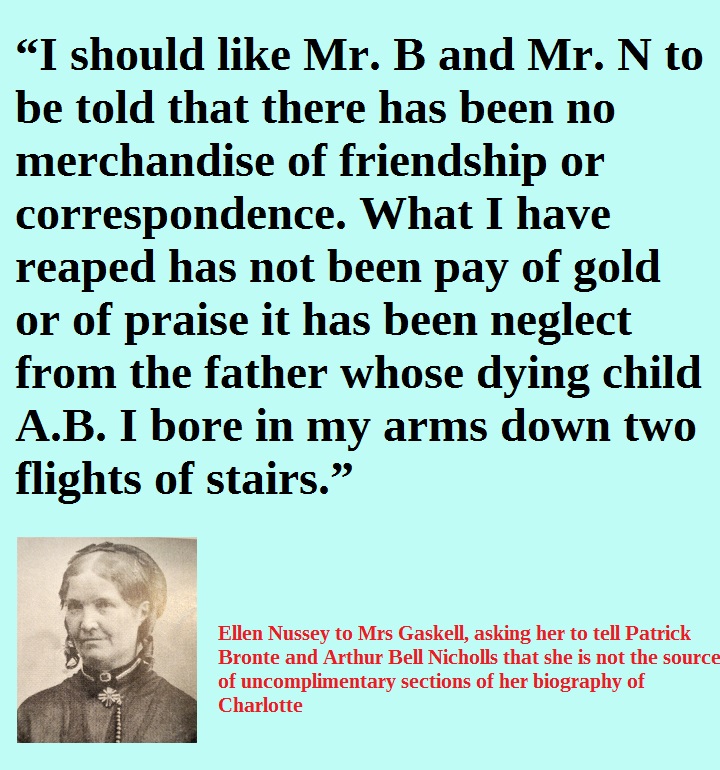

Already the strain brought on by the book, and an almost constant stream of letters from solicitors and unhappy individuals, is making Elizabeth Gaskell unwell. Ellen Nussey, too, had cause to write to Elizabeth. One sad aspect of the book’s publication is that Patrick and Arthur blamed Ellen for the sections of the book they were unhappy with, although again we now know that she was not the source for those parts of the biography. They cut off the woman who had been Charlotte’s best friend, and a lifelong animosity grew between Ellen and Arthur. With a moving plea, she too wrote to Elizabeth Gaskell:

By November 1857 a third edition of The Life Of Charlotte Brontë was published. It bore the legend ‘revised and corrected’ it should really have read ‘censored’. Elizabeth Gaskell had tried to portray her great friend Charlotte Brontë as she knew her, a woman of genius and a woman with a huge heart, but although her efforts sold well they brought her grief and anxiety. She later wrote to her publisher George Smith to lament that ‘every one who has been harmed in this unlucky book complains of some thing.’

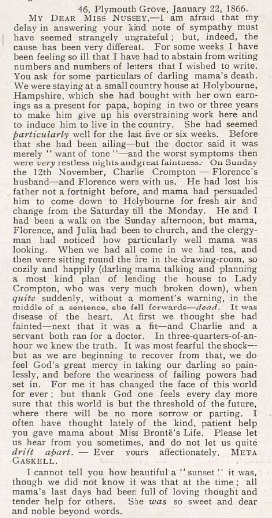

These complaints continued over the next decade until on 12th November 1865, eight years after the publication of the biography, Elizabeth Gaskell died suddenly in the middle of a sentence. We know this thanks to a letter sent by her daughter Meta to Ellen Nussey in January 1866:

The postscript is interesting here, as although we don’t have her letter it is clear that Ellen has asked about Elizabeth Gaskell’s ‘sunset’. This brings to mind her description of the last night of Anne Brontë’s life; Ellen wrote that Anne was looking out of the window across Scarborough’s South Bay, and that she witnessed the most ‘glorious sunset’ ever seen. Some have pointed out that the sun rises over the South Bay rather than setting in it, but it seems clear to me now that Ellen habitually used the phrase ‘sunset’ to refer to the closing of a life.

Did the stress caused by the aftermath of the publication of The Life Of Charlotte Brontë hasten the end of Elizabeth Gaskell’s life? We shall never know, but we can be sure that she regretted its publication. We can’t regret its publication however because, for all its flaws, it is a brilliant biography that reveals so much of what we know about the Brontës today.

Thank you to all who supported the Kickstarter project for Hanover Press after last week’s post – with your help we will be rescuing some neglected classics of Victorian literature in 2021. Stay well, stay happy, and I will see you here for another Brontë blog post next Sunday.

If this is so — especially the idea that the publication of this book at least weakened her health, what an ironic tragedy. I’m one who thinks it a powerful biography, the first genuinely genius level one for a woman writer. It ought to be spoken of in the same breath as Boswell’s for Johnson. I also still think her portrait of the Bronte father tells us important truths about the man and thus his children.

It’s a case of a woman’s book which were it by a man about a man would today be far more respected and taken its rightful place in the history of a thriving genre.