The year draws to an end and we’re just a few days away from Christmas and all that brings (which may be slightly less than usual in this oddest of years). As promised, I want to bring you something truly special today: a glimpse into the lives of the Brontës from those who actually knew them. It’s a long post but, I hope you’ll agree, packed with fascinating detail. We’ll hear from Haworth villagers at the time of the Brontës, and from two of the people who knew the Brontës better than most: Charlotte’s widow Arthur Bell Nicholls and Charlotte’s friend and long time parsonage servant Martha Brown. I guarantee that you won’t have read most of these accounts before.

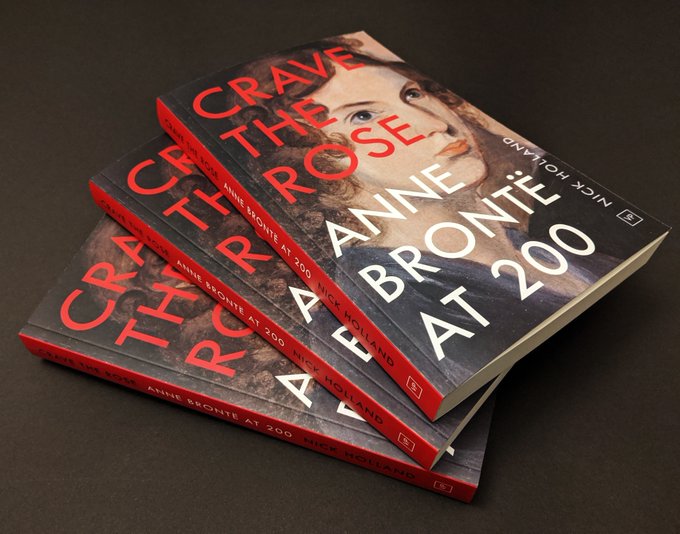

I love delving into the archives and finding stories of the Brontës that have become lost through the passage of time, and over the years I’ve accumulated a large collection of them. Some of my favourites are reproduced below, but as this year is Anne Brontë’s special year we will begin with two accounts that feature in my book Crave The Rose: Anne Brontë At 200. I do this partly to promote the publisher of the book, Valley Press, an independent little publishing house in Anne’s beloved Scarborough who like so many others must have been having a tough time this year. Take a look at their website, they have a great collection of books and every purchase helps. I’ve chosen these two first person accounts from the many in Crave The Rose because they shine a sweet light on Anne’s character. I will then follow these with half a dozen accounts which you won’t find in that book, or any other. I hope you enjoy them, so let’s begin by stepping back into a winter day in Haworth over a century and a half ago:

A Winter-Day In Haworth, Chamber’s Journal, 22 February 1868

‘Standing beside Charlotte’s last resting place, I questioned my conductor respecting her, and found him at once ready and willing to oblige me with all the information in his possession. “He had been but a little boy,” he said, “when all the family were living, but he remembered the three sisters well, and had often run errands for Mr Patrick. They used to take a great deal of notice of him when he was little; but Miss Annie was his favourite, perhaps because she always paid him so much attention. Baking-day never came round at the parsonage without her remembering to make a little cake or dumpling for him, and she seldom met him without having something good and sweet to bestow on him.

Yes, they were a very reserved family, and very peculiar in their habits. The villagers did not see much of them, except on Sundays; and of course nobody knew that the young ladies were writing books, or that they had become famous, until, long after, strange people had begun to come from a distance to see them. And then the letters! What a heap of letters were always brought to the parsonage in those days by the postman!

Miss Emily, who is buried here, beside Charlotte, was the strangest of all the family; nobody thought so much of Miss Charlotte herself. Emily never came down into the village, or at least very rarely; but here, through the window, I might see the path by which she used always to go from the parsonage from to the moors. Hundreds of times, when he was a boy, he had watched her go through the stile yonder, followed by her dogs. No matter what the weather was, she loved the moors so much that she must go out upon them, and enjoy the fresh breezes. When she went away from Haworth, to become a governess, she was taken very ill, and sickened until she was brought home again, and then she very soon recovered. She loved the moors so much, that it would have been a sad thing if she had been buried away from them.

Of course I had read Mrs Gaskell’s book, and the way in which she had refused to see a doctor until an hour or two before she died. About Miss Charlotte, he could not tell so much, she was so very reserved; but he remembered seeing her stand, just where he was standing now, that morning when she was married. To his mind, Mr Branwell was the cleverest of the family. A wonderful talker he was, and able to do things which nobody he had ever seen could do. He had seen Branwell sitting in the vestry, talking to his (the sexton’s) father, and writing two different letters at the same time. He could take a pen in each hand, and write a letter with each at once. He had seen him do that many times, and had afterwards read the letters written in that way. Yes; it was true that he had come to a sad end, but Mrs Gaskell had not stated the case about him correctly.

Haworth people did not like Mrs Gaskell at all. There was a deal of feeling against her for what she had said about Mr Branwell, and the villagers encouraging him to drink. Mrs Gaskell said that he had learned to drink as a boy, and had gone on strengthening his habit; but that was not true. When he was nineteen years old he was secretary to the temperance society in the village, and it was not until after that that he learned to drink. It was not correct that the landlord of the Bull had anything to do with teaching him, though it was quite true that he used to sit in the back parlour there and drink almost constantly of an evening when he was older. But if he could not have got drink there, he would have been sure to have got it somewhere else. But, oh, he was a fine talker Branwell; and such a talker! Ay, and when he was at the worst, he never missed coming to the Sunday school with his sisters. They all used to come regularly.

He remembered Mr Branwell’s funeral, and Miss Emily’s funeral, and of course he remembered Miss Charlotte’s and Mr Brontë’s. A strange old gentleman was Mr Brontë – Mr Nicholls, who married Miss Charlotte, was very well liked by the people. A true gentleman he was, though very shy and reserved; but how could he help being that, when he had lived so long with such a family? When Mr Brontë died he “put in” for the place; but when he found out there was likely to be opposition, he withdrew, and now he was living in Ireland again, where he had married a second wife. With such pleasant garrulousness did my companion entertain me, even while I stood beside the grave in which ‘life’s fitful fever’ o’er, the bones of Charlotte Brontë rest.’

Old Haworth Folk Who Knew The Brontës, Cornhill Magazine, 29 July 1910

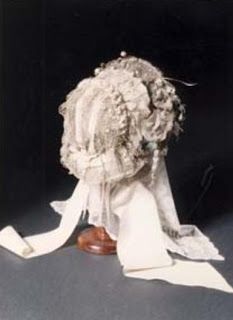

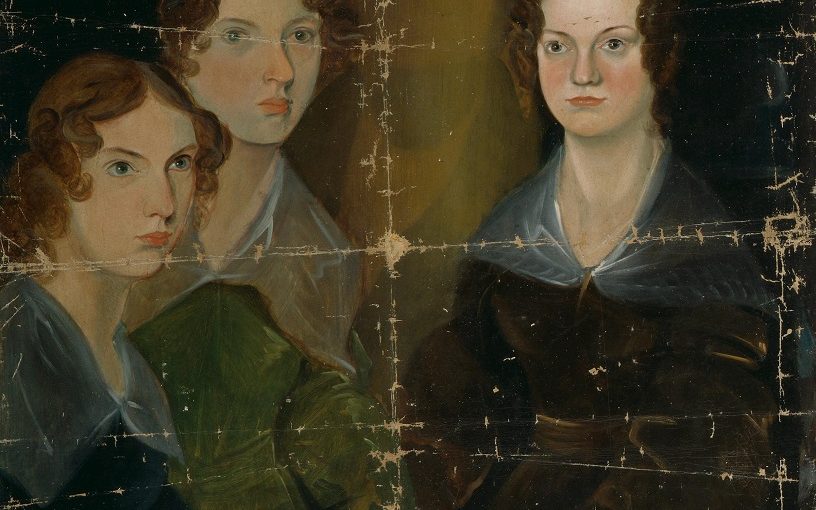

‘She [Tabitha Ratcliffe, younger sister to long time Brontë servant Martha Brown] still preserves a few mementoes of the various members of the family: of Miss Branwell a silk shawl, of Mr Brontë a small hammer he used to use, and of Charlotte a delaine skirt and a white sprigged net veil – which latter has served as a christening veil for several of her grandchildren. Perhaps, however, her most interesting relic is a photograph on glass of the three sisters. “I believe Charlotte was the lowest and the broadest, and Emily was the tallest. She’d bigger bones and was stronger looking and more masculine, but very nice in her ways,” she comments. “But I used to think Miss Anne looked the nicest and most serious like; she used to teach at Sunday school. I’ve been taught by her and by Charlotte and all.” And it is on Anne that her glance rests as she says, “I think that is a good face.” There is no doubt which of the sisters of Haworth was Mrs Ratcliffe’s favourite.’

Camera And Pencil In Charlotte Brontë’s Country, Batley Reporter And Guardian, 3 April 1897

Brontë students must not read this free-and-easy record of a week-end in the Brontë country. It is for laymen who have conned with delight the immortal Jane Eyre and the fascinating Shirley; but who have never read Mrs. Gaskell’s Life Of Charlotte Brontë, or had the patience to wade through the plethora of letters in Mr. Clement Shorter’s recent work.

The bright sunshine of early morning on a Saturday in windy March gladdens the heart of the gentleman who has promised to accompany me in our little exhibition, with the object of pictorially reproducing the scenes that we visited… A quarter of an hour’s journey, and the porter sonorously shouts “Howarth” – caring not a fig for the laws of orthography – and, with stand and portfolio, we alight at a little station unknown in Charlotte Brontë’s day, and suggestive of the changes of the past thirty or forty years…

The homeward journey is relieved by a humorous dialogue with the Man of the Moor, a self-centred, self-opinionated keeper, who has known no society but the lonely moor for a quarter of a century. ‘Old Bluche’, the sobriquet in which he rejoices, followed by pointer and setter, is making tracks for his cottage on the moor. He looks too much of a character to pass without challenge…

“Ha wish Charlut Bronty ha’ ta’en t’waterfall wi’ her. She’d a’ saved me a lot o’ truble.”

“What for?” I enquired.

“Wha, I doan’t min’ yer lads and lasses goin’ to t’waterfall, but yer mun stick to tu’t path and noan wander o’er my moor.”

Upon hazarding that the moor not was the place for the preservation of game and the exclusion of man, he rejoined,

“Ah, they cum here wanderin’ o’ert’ Moor, stealing t’eggs, flaying t’ung birds. It’s a peety she ha’ na’ ta’en her waterfall wi’ her. If they’d only move it neer t’edge ot Moor, I wudent care.” Then, menacingly pointing to the innocent guide – “It’s lads loike that that cums taking t’eggs, that bothers me.”

“Then you are not an admirer of Charlotte Brontë?”

“Noa, I’m not. I doan’t believe i’ her. She niver wrate them books ‘at they talk abaut.”

“Not wrote the books? Who did then?”

“Wha, she didn’t; poor, waik little thing. Sum geentlefowks met together an’ boxed them up for her.”

More light on the Brontës at Haworth!

A little friendly chaff on his startling literary theory and his geographical knowledge, and he makes another alarming assertion, which leads us to associate the place of his nativity with Paddy’s Land –

“I’ve niver bean out of Yorkshir – but I’ve been in Dublin.”…

From the bleak and wintry moor, now covered with snow, which had been falling fast for hours, asylum is sought in the humble cottage of a devout and infirm couple, who have climbed the hill together, and are going down into the valley happy in each other’s society, and with buoyant hope for the future. Both of them knew the Brontës; both talked freely about them, especially the aged veteran, who, puritanical as he now is, would hear nothing against the erring Branwell worse than that “he wor fond o’ a bit a cum-pony.”’

An Interview With Charlotte Brontë’s Husband, Yorkshire Post, 12 September 1893

The tardy revival of public interest in the Brontë literature brings to light an interesting fact. The Rev. Arthur Bell Nicholls, Charlotte Brontë’s husband during the last nine happy months of her life survives her. His old age is passed among his own people in the South of Ireland, where, highly esteemed by the peasantry and all about him, as he was by those who knew him best at Haworth, he follows the career of a gentleman farmer…

Mr. Turner’s interview with him [Arthur] seems to have given him the liveliest pleasure. It was accorded very readily, and it introduced him to an excellent host. “I should not”, he [Brontë biographer and Arthur’s interviewer Horsfall Turner] says, “have known him from the photograph. This is nothing less, indeed, than a caricature. You would fancy him as you look at it a curt, snarling, heavy-jawed, morose Hibernian. But I had learnt something of him from Martha Brown, who was long his trusted servant, both at Haworth and at his Irish home, and the moment I felt the hearty grip of his hand I was at home with him. We were seated in his drawing-room, with the kind eyes of Richmond’s own drawing of Charlotte streaming down their lustrous expression upon us… Next I eyed more carefully my host – a genial, well-built, healthy, ruddy-faced, strong-haired gentleman, in manner, mind and matter as different from the usual portrayal of him as chalk and cheese. Sunviter in modo, fortiter in re is the best description I can give of his bearing [gentle in manner, strong in deed]. I could get on with him well; nay, I already revere him. He is the country gentleman, not only cultured, charitable, manly, but Christ-like.

The Richmond portrait, as it hung in the parlour of Haworth Parsonage, had for company, as most people will remember, portraits of the Duke of Wellington and Thackeray (the latter a gift of the author) to which, said Charlotte, in one of her playful moods, “It serves for contrast and foil. Thackeray looks away from it with a grand scorn edifying to witness”. These, too, are in Mr. Nicholls’ drawing-room, with five lead-pencil drawings – copies of engravings, minute in detail – of which three bear the “printed” autograph of Anne Brontë, and the other two are Charlotte’s work. He has, besides, Emily Brontë’s coloured crayon drawing of her two favourite dogs and her cat. Finally, of Patrick Branwell Brontë there is a massive framed medallion, sculpted by his friend Leyland, of Halifax – a high-relief profile in white marble…

“I specially asked,” he [Turner] writes, “about the last walk of Mr. and Mrs. Nicholls to see the water fall in flood, and was corroborated in the belief that the fall in question is that which is usually called the Brontë Fall, near the parsonage at Haworth. We spoke about closely identifying characters in the novels with Charlotte’s relatives and acquaintances and he joined in the deprecation. We spoke of Miss Martineau and Mrs. Gaskell and the misunderstandings that were afterwards rectified so far as the former was concerned. This led me to state that one of the most remarkable puzzles to Brontë students is the silence that he has preserved ever since Mrs. Gaskell’s memoir appeared. I now believe that both Mr. Brontë and Mr. Nicholls had the best motive for this silence, and exercised the rare gift of Christian charity in preserving it. Mr. Nicholls has borne obloquy with patience and courage; in the long run he will be duly appreciated… Not long after his return to Ireland he married again. His second wife, who is unfortunately an invalid, was a Miss Bell, one of his cousins.”’

A Visit To Haworth, Batley Reporter and Guardian, 13 September 1873

‘For years I had felt a desire to visit what was the home of the Brontë family, and to have a peep at the district which they have made for ever famous. I had read their wondrous books with a pleasure that many people cannot understand, and had become more and more interested in their home and haunts. Accordingly, I and a friend determined that we would have a day over there, come what might, and fixed on 3rd September as the date… There is a pretty little wooden station at the foot of the village, although the train service between Haworth and Keighley is not of the most accommodating character.

As we had plenty of time before us we sat down a little and enjoyed the beauties of the morning scene. We had not been sat long before we were joined by a personage of the exact character that Mrs. Gaskell’s book would make one expect to meet in Haworth. We were soon in conversation with him, and found that he had been particularly acquainted with the Brontë family. He was a farmer just outside the village, and the old vicar and his daughters used to come very morning to his house for milk, generally accompanied by a large dog. He had talked with them all “scores of times,” and was very well acquainted with Branwell, whom he said had been “led off before he became a man.” As we had read much of the conduct of the father towards his children, and his treatment of them, we thought that they who had lived around them for a life time would be best able to tell. In answer to our enquiries he said that he “was as good a father as ever lived,” and also that “niver a quieter man ever lived.” We made the same enquiries of different persons during the day, and received similar answers to the above… Our friend at the station however admitted that he [Patrick Brontë, although the interviewer may be getting him confused with Branwell] used to get a little too much to drink occasionally, and told of once bringing him home in a drunken state and telling parties he had had a fit. For the above service he reinstated himself in the good graces of Miss Branwell who had once run him away from the parsonage with a pistol in her hand…

Before we reached the village, we met with another old villager, who in answer to a question in our conversation with him, said he “Knew all t’lot on ‘em.” He knew Branwell particularly well, and had often met with him at the Black Bull and other places. He said “he wor a trimmer”, an expression that the reader may explain for himself. On questioning him further respecting Branwell, he said “he was as gooid a fellow as ivver brake bread.” He told us that if any one had gone to him and read a passage from a book, he could at the conclusion have repeated the whole of it…

We sought out the residence of the sexton and got his wife to show us round the place… The woman said she had been one of the scholars in Miss Charlotte’s class in the Sunday school, and also told us that she was a good teacher, but “rather sharp.” All the sisters she said were very kind, but Annie was the most gentle. She well remembered the incident which is so often related respecting Emily, viz., her being bit with the dog, and coming home, and without a murmur burning out the part with a red hot iron.’

A Pilgrimage To Haworth, Leeds Mercury 4 March 1893

‘On the particular pilgrimage which forms the subject of the present sketch, I, in company with an antiquarian friend of like tastes, chose this as our route on a fine day fifteen summers ago… Haworth was now soon reached, and as the chief object of our visit was to have an interview with Martha Brown, the faithful servant of the Brontës for many years, we were not long before ourselves seated in her small, but clean and comfortable, dwelling at the bottom of the village…

Though by no means demonstrative in manner, Martha gave us a cordial greeting, and had a happy way of making us feel “quite at home,” as she termed it. Of course, the chief topic of our conversation was the Brontë family. Her reminiscences of the members of that family abound in references to their uniform kindness to herself and others. “From my first entering the house,” she said, “I was always recognised and treated as a member of the family, although by outsiders I was spoken of as the servant girl”…

Peeling the potatoes for dinner was one of Tabby’s duties, but from her partial blindness she was unable to see and cut out the black specks known as the ‘eyes’ of the potato. “Miss Brontë was too dainty a housekeeper to put up with this, yet she could not bear to hurt the faithful old servant by bidding the younger maiden (Martha) to go over the potatoes again. Accordingly, she would steal into the kitchen, and quietly carry off the bowl of vegetables without Tabby’s being aware, and, breaking off in the full flow of interest and inspiration in her writing (Jane Eyre), carefully cut out the specks in the potatoes, and noiselessly carry them back to their place.”…

Although she spoke in a quiet, subdued tone, her narrative would sometimes become animated, even thrilling; at others deeply pathetic. Especially touching was her description of Charlotte’s maternal anxieties for her younger sisters, and the strong attachment each had for the others. She also told us of the long rambles on the moors; of the regular habits of indoor life; the putting away of domestic work punctually at nine o’clock in the evening, and their beginning their literary studies, talking over the stories they were engaged upon, and describing their plots. “Many’s the time that I have seen Miss Emily put down the tally-iron as she was ironing the clothes to scribble something on a piece of paper. Whatever she was doing, ironing or baking, she had her pencil and paper by her. I know now that she was then writing Wuthering Heights.”

When old Tabby became so lame that she had to give up her work for a time, Charlotte and Emily, who were then at home, divided her duties betwixt them, the former doing the ironing and keeping the rooms clean; the latter the baking and attending generally to the kitchen. “Poor Emily,” said Martha, “we always thought to be the best-looking, the cleverest, and the bravest-spirited of the three. Little did we dream that she would be the first to be taken away.”

Martha had many interesting things treasured in her memory concerning Charlotte Brontë’s literary career. When news first came to Haworth that Miss Brontë was the author of Jane Eyre and Shirley, Martha was the first to bring it to the parsonage. She rushed to the house in the greatest excitement, exclaiming, “I’ve heard such news!” “What about?” inquired Miss Brontë. “Please, ma’am; you’ve been and written two books – the grandest books that ever was seen. My father has heard it at Halifax, and Mr. T-, and Mr. G, and Mr. M-, at Bradford. They are going to have a meeting at the Mechanics Institute to settle about ordering them.”…

The former [Charlotte Brontë] did not much care to talk about either herself or her book, but these were themes on which Martha, for the very life of her, could not be silent, and talk about them she would. “Well, Martha,” said Charlotte, “I only hope the book may be worth all the fuss that is being made about it, but I am afraid it is not.” Taking a very practical view of the subject, and wishing to say something by way of encouragement, Martha replied, “Oh, but you must please not forget the good that your book must have done in supplying employment to so many people. Look at the printers, bookbinders, stationers, and others who have been benefitted by its large sale.” “Thank you, Martha, for putting it in that light,” said Miss Brontë, “I am sure I had never thought of that.”

Martha Brown assured us that Miss [Charlotte] Brontë had been advised, on more than one occasion, to change her publishers, on the ground that the great popularity of her writing would now command a higher figure than she had hitherto received. Charlotte would not, however, hear of this, and replied that Messrs. Smith, Elder, & Co, had been pleased to accept her manuscripts after they had been rejected by other publishers, and unless they forsook her she would never forsake them.

Martha was unstinted in her admiration of Emily Brontë. Although silent and reserved in the presence of strangers, she was ever regarded by those who knew her best as the very embodiment of truth and honour… Martha was very indignant at the hard things that had been said about old Mr. Brontë by Mrs. Gaskell and others. “A kinder man could not be, although he was sometimes queer and reserved before strangers.” As to his discharging pistols into the air as a means of letting off his bad tempers, the tale was without the slightest foundation. “Mr. Brontë always was fond of firearms,” she said. “He had acquired this fondness from his having been a Volunteer whilst at college.” She never saw him discharge one in passion.

It was Martha Brown’s loving duty to wait upon her mistress, Mrs. Nicholls, during her illness. Very touching was her narrative of the last moments of the brave and patient sufferer. Even when utterly prostrated by weakness and pain, her thoughts were more occupied with anxiety for her old father, who was so soon to be left desolate, than for her own intense sufferings. When she heard him coming upstairs to see her, she would ask Martha to let her sit up a moment, and would then strain every nerve to give him a pleasing reception. On his entering the room, she would greet him with, “See, papa, I am looking a little better.” The old man would then retire, trying to look comforted, while the poor patient would fall back upon her pillow all but exhausted by the effort she had put forth.

The wasting form told but too sad and true a tale of the end that was not far off. Early on the morning of March 31st, 1855, the bell in the tower of the old church at Haworth gave out the sad news that Charlotte Brontë was no more. The grey old parsonage was now very silent and solitary. Martha Brown remained with the bereaved parent until his death in 1861, and was one of the sorrowful mourners who followed him to his grave.’

The Home Of The Brontës, York Herald, 19 April 1890

‘It is a mistake to suppose that the memory of the Brontës is dying out in the place which once knew them so well. Every old villager we spoke to – and there were not a few – had something to say, and usually some reminiscence on the subject. The names of ‘Charlotte’, ‘Emily’, and ‘Branwell’ dropped easily and familiarly from their lips; and yet there was nothing impertinent, nothing the least disrespectful, in the sound; it merely seemed as if these simple folks cherished a hallowed remembrance, with which any of the ordinary forms of speech would have been incompatible. One nice little matron, with a chastened, subdued demeanour and a face that plainly told life to her had been no child’s play, had perhaps more to tell than all the rest about the Brontës. She had seen ‘Mrs. Nicholls’ pass into the church in her bridal attire on the wedding morn – “very plain, but Charlotte always was very plain in her dress;” and again had seen her re-enter the same churchyard gates but a few brief months later, when carried to her grave.

“She was never very intimate, never at all freespoken with the Haworth people.” “Oh, they liked her; nobody had ever a word against her; but it was understood that she, and indeed all the family, liked best to be alone. Charlotte would come and go. She was a very quick walker, and she would turn the corner of the parsonage lane and be down the street all in a moment: and then she would drop into the shop” – (we were sitting in the shop as we listened) – “order what she wanted, and be off home again at once, without a word more than was needed. My father,” continued the narrator, “had always himself to take the cloth, or whatever it was that had been ordered, up to the parsonage, when his work was done; and he had to measure it there and cut off the length required. No, none of them would ever have it measure and cut off in the shop; it had to be taken up in the piece to the house, and cut there. The Brontës had ways of their own, and that was one of them. They were strange people, but very much beloved. Mr. Brontë was a fine old gentleman” (with a sudden little glow of warmth), “a very fine old gentleman” (most emphatically); and the speaker had heard that there were some who had written about Charlotte, and made up books about her, “who had not spoken quite true about Mr. Brontë.” All she could say was that “there was no one in Haworth now living who had not a good word for the old gentleman, and to see him and Mr. Nicholls together after they were left alone, and poor Mr. Brontë so helpless and blind, was just a beautiful sight – that it was.” She would have discoursed till midnight, but time pressed. We had to move on, and hearken to others.’

An Opposite Opinion, Pall Mall Gazette, 14 October 1889

‘Before bringing these reminiscences to a close, it is pleasant to record the account given by another lady of a visit to Haworth a few years ago. So great is the growth of population in the district around Keighley and Haworth (to which the railway now extends) that the desolate loneliness of Haworth Parsonage and the moors beyond, so graphically described by Charlotte, can now be scarcely realized. On visiting the church and looking at the Brontë tablet, with its pathetic record of eight deaths, this lady got into conversation with one of the older generation of Haworth women, who though at first (with true Yorkshire caution) a little suspicious of a stranger, eventually spoke freely and in the most affectionate way of Miss Brontë, mentioning as one of her chief characteristics the shyness and reserve of which the authoress herself was so painfully conscious. “She never raised her eyes from her book when in church,” said the good woman. How clearly the picture rises before our mental vision! The tiny but well proportioned figure; her dress exquisitely neat, but perfectly plain; her face without pretension to beauty, but with the light of genius shining bright and clear through her expressive eyes. Here, in the old church, plain and unpretending like herself, where for so many years her prayers and praises went up to the God in whom she never lost her trust, we can most fitly take our leave of Charlotte Brontë.’

We must fitly take leave of these first person accounts of the Brontës now; through their encounters we too can encounter them as the flesh and blood people they were, as if the intervening years had drifted away on a December breeze. Thank you for sharing this post with me, and, whatever your faith, I hope you can find time to join me here on Thursday for a Brontë Christmas Day post.

Thank you for this and hope you have the best possible Christmas and New year.

Fascinating post! Really brings the Brontes to life. Thank you, Nick, and best wishes for a wonderful Merry Christmas!

Thank you for this delightful collection. I lived in West Yorkshire from 1972 to 1983 when I moved to London. While there I visited Haworth, the town , the parsonage and the surrounding moors on several occasions. I decided about this time last year that during 2020 I would have a holiday in Yorkshire and revisit various places, including Haworth! Ah well, maybe next year…

What a wonderful post. Such a glorious Christmas present to your readers. It makes me want to choose them as the subject of my next book.

Wonderful. Thank you for the insights. Reading about the Brontes always makes for a better understanding of their novels & poetry. Reading credible historical documents such as these also lends sound facts for my own writing of historical novels.

Let me spoil it a bit. All but Tabitha Ratcliffe seem to forget about Anne… which only makes Tabby’s reminiscence more precious. “Miss Anne looked the nicest and most serious like.” An unusual combination. Anne and Emily will always be a mystery.

P. S. Merry Christmas!

Thank you, Nick for this very interesting post and the excellent pictures. Best wishes for 2021.

A very interesting Christmas garland – thank you. I wonder if there are other accounts which corroborate the 1868 description of Branwell’s ambidexterity – writing with both hands at the same time is known but (not surprisingly) rare.

Fascinating to hear the thoughts of people who knew them. Thank you for writing this, and I hope you you have a good new year to come!

Thank you for such an interesting article, and, particularly, thank you for including Branwell. There is much written about the sisters but very little about Branwell yet his story is both interesting and rather tragic. Have you read Francis Leyland’s book (in two volumes) on the Brontes with particular reference to Branwell? Francis as brother of Joseph Leyland, Branwell’s close friend was in a position to know more about him than most. To me poor Branwell seems to have many of the symptoms of Bi-Polar disorder, it’s sad that he’s either ignored or vilified by history. Mrs. Gaskell wrote excellent fiction but she included a great deal of fiction in her biography of Charlotte Bronte too, she let her friendship for Charlotte get in the way of the truth, especially when it came to the male members involved in the story of her heroine.