Many people made a lasting impression on Anne, Emily and Charlotte Brontë – people such as Ellen Nussey, Mary Taylor, George Smith and Margaret Wooler. This week marks the anniversary of the passing of a woman who certainly made a lasting impression upon Charlotte Brontë and influenced her work, but they weren’t necessarily the best of friends. In today’s post we’re going to look at Madame Claire Heger, the prototype of Madame Beck in Villette.

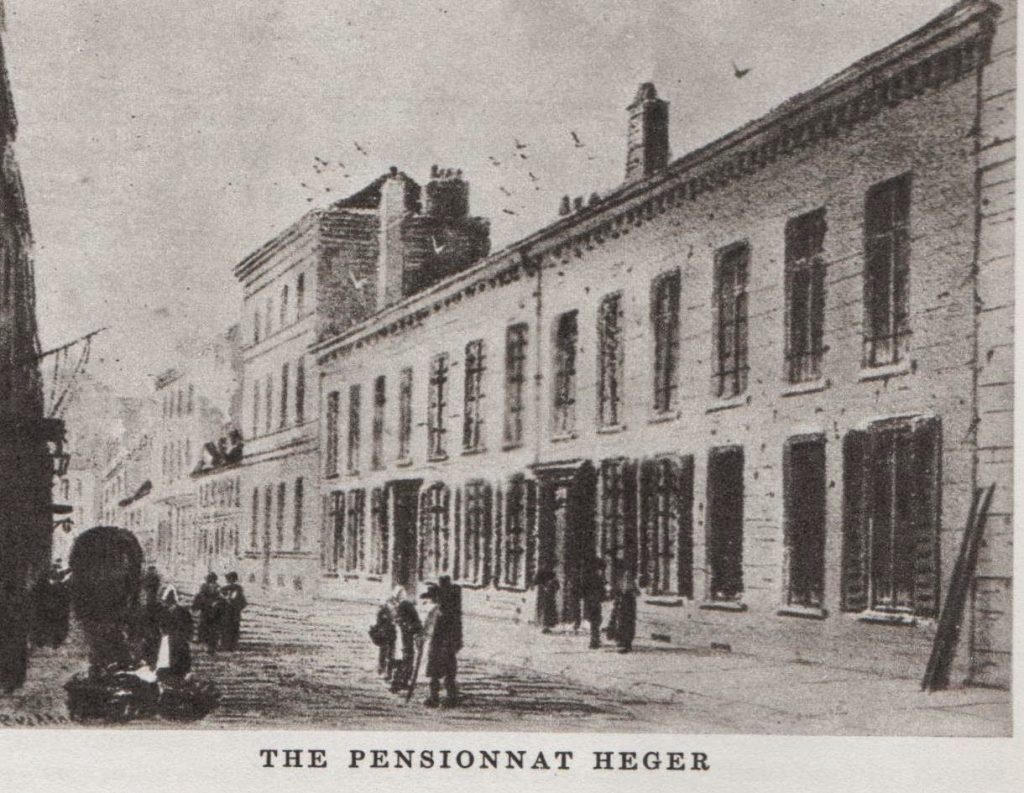

Claire Zoë Parent was born in 1804 in Belgium to a French father, but perhaps the most significant relative, for our story, was her aunt. This aunt was a nun who ran boarding schools in Brussels, with a girl’s school and boy’s school adjacent to each other. It may be supposed that Clare worked as a teacher in that school for in 1830 she inherited the establishment, known as a Pensionnat. By 1842, at the time that two new English pupils arrived at the school on the city’s Rue d’Isabelle (Charlotte and Emily Brontë of course) it bore a plaque outside hailing it as the ‘Pensionnat de Demoiselles Heger-Parent.’

Charlotte would always remember the moment she arrived at the school, and recreated it in the guise of English born teacher William Crimsworth in her first-written novel The Professor:

‘I saw what a fine street was the Rue Royale, and, walking leisurely along its broad pavement, I continued to survey its stately hotels, till the palisades, the gates, and trees of the park appearing in sight, offered to my eye a new attraction. I remember, before entering the park, I stood awhile to contemplate the statue of General Belliard, and then I advanced to the top of the great staircase just beyond, and I looked down into a narrow back street, which I afterwards learnt was called the Rue d’Isabelle. I well recollect that my eye rested on the green door of a rather large house opposite, where, on a brass plate, was inscribed, “Pensionnat de Demoiselles.” Pensionnat! The word excited an uneasy sensation in my mind; it seemed to speak of restraint. Some of the demoiselles, externats no doubt, were at that moment issuing from the door – I looked for a pretty face amongst them, but their close, little French bonnets hid their features; in a moment they were gone.’

Let’s head back to see how Claire Parent is doing as Directrice of her own school. In 1833 she hired a new Professor for the boy’s school which was named the Athenee Royal. Constantin Georges Heger was 24 but had already experienced tragedy in his life. He came from a wealthy family but the fortune had been lost and the young Constantin moved to Paris to seek his own way in life as a lawyer. In 1830 he married Marie Josephine Noyer but she, along with their son, died in 1833 and Constantin returned to his home city of Brussels. It was in the direct aftermath of this double tragedy that he was hired by Claire Parent to teach at the Athenee Royal. She must have helped to heal his broken heart, for three years later they were married and Claire became Madame Heger.

Within ten years of their marriage they had (like Patrick and Maria Brontë) six children: Marie, Louise, Claire, Prospere (born in the year the Brontës arrived in Brussels), Julie and Paul. That’s the happy Heger family at the top of the post, painted by Ange Francois. Claire is centre stage, although her husband Constantin is looking on rather furtively from the left as if he’s about to sneak off whilst his wife’s back is turned.

The story is well known of how Charlotte Brontë spent time as both a pupil and then teacher in Brussels, and of how she came to fall in love with Professor Constantin Heger. We only need to look at the despairing letters that Charlotte sent back to Brussels after her return to Haworth at the commencement of 1844 to see this, including one sent on 8th January 1845 in which she writes: ‘Pardonnez-moi donc Monsieur si je prends le partie de vous ecrire encore – Comment puis-je supporter la vie si je ne fais pas un effort pour en alleger les suffrances?’

Let’s have it in English, and see just what suffering the departure from Constantin caused Charlotte:

This letter and others sent from Charlotte to Constantin were first published in 1913 by ‘The Times’ newspaper, and they caused an uproar. Up until then the prevailing orthodoxy was that Charlotte had not been in love with Constantin at all, but these letters proved otherwise and challenged the Victorian attitudes of propriety which were still holding firm among the chattering classes. The general opinion in 1913 was that the letters should have been destroyed rather than published, but thank goodness that they were brought to life for it allows us to see a passionate, human side of Charlotte Brontë that we can surely all sympathise with, and it gives us a first hand insight into the events and emotions that shaped The Professor and Villette and which influenced the character of Rochester.

We can have no doubt that poor Charlotte fell head over heels for Monsieur Heger, although you might not guess that from her first mention of him in a May 1842 letter to Ellen Nussey:

‘There is one individual of whom I have not yet spoken: Monsieur Heger the husband of Madame. He is professor of Rhetoric, a man of power as to mind but very choleric and irritable in temperament – a little, black, ugly being with a face that varies in expression. Sometimes he borrows the lineaments of an insane Tom-cat – sometimes those of a delirious hyena – occasionally, but very seldom, he discards these perilous attractions and assumes an air not above a hundred degrees removed from what you would call mild and gentleman-like.’

In this same letter Charlotte also introduced Claire Heger:

‘Madame Heger the head is a lady of precisely the same cast of mind, degree of cultivation & quality of character as Miss Catherine Wooler [this sister of Margaret Wooler had taught Charlotte at Roe Head and was renowned for her aloofness and severity]. I think the severe points are a little softened because she has not been disappointed & consequently soured – in a word she is a married instead of a maiden lady.’

By the following year, Charlotte’s views on Claire had hardened, as she expressed in a letter to her sister Emily dated 29th May 1843:

‘Of late days, Mr and Mde Heger rarely speak to me, and I really don’t pretend to care a fig for anybody else in that establishment. You are not to suppose by that expression that I am under the influence of warm affection for Mde Heger. I am convinced that she does not like me – why, I can’t tell.’

Perhaps the clearest indication of Charlotte’s feelings towards Claire Heger (although once again hidden by another name) is given via the depiction of Madame Beck in Villette – clearly a depiction of Madame Heger herself.

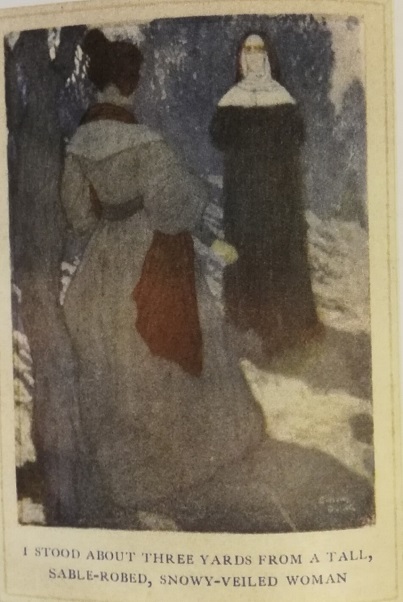

Madame Modeste Beck is the cool and calculating head of the Pensionnat de Demoiselles; she is not averse to spying on pupils and staff alike, and ruling them with a rod of iron. She is the antagonist of Lucy Snowe, doing all she can to keep Lucy from Monsieur Paul, and Charlotte Brontë is unsparing in her description of her:

‘About noon, I was summoned to dress Madame. (It appeared my place was to be a hybrid between gouvernante and lady’s-maid.) Till noon, she haunted the house in her wrapping-gown, shawl, and soundless slippers. How would the lady-chief of an English school approve this custom?

The dressing of her hair puzzled me; she had plenty of it: auburn, unmixed with grey: though she was forty years old. Seeing my embarrassment, she said, “You have not been a femme-de-chambre in your own country?” And taking the brush from my hand, and setting me aside, not ungently or disrespectfully, she arranged it herself. In performing other offices of the toilet, she half-directed, half-aided me, without the least display of temper or impatience. N.B.—That was the first and last time I was required to dress her. Henceforth, on Rosine, the portress, devolved that duty.

When attired, Madame Beck appeared a personage of a figure rather short and stout, yet still graceful in its own peculiar way; that is, with the grace resulting from proportion of parts. Her complexion was fresh and sanguine, not too rubicund; her eye, blue and serene; her dark silk dress fitted her as a French sempstress alone can make a dress fit; she looked well, though a little bourgeoise; as bourgeoise, indeed, she was. I know not what of harmony pervaded her whole person; and yet her face offered contrast, too: its features were by no means such as are usually seen in conjunction with a complexion of such blended freshness and repose: their outline was stern: her forehead was high but narrow; it expressed capacity and some benevolence, but no expanse; nor did her peaceful yet watchful eye ever know the fire which is kindled in the heart or the softness which flows thence. Her mouth was hard: it could be a little grim; her lips were thin. For sensibility and genius, with all their tenderness and temerity, I felt somehow that Madame would be the right sort of Minos in petticoats… “Surveillance,” “espionage,” – these were her watchwords.’

There can be no doubt that Lucy didn’t get on with Madame Beck, nor did Charlotte get on with Madame Heger, but why? The answer clearly lies in Charlotte’s affections for Claire’s husband Constantin. He never replied to Charlotte’s letters after her return to England, and they grow ever more desparate. Indeed, they have been torn into pieces and then stitched back together again. Perhaps Constantin meant to destroy the evidence of this unrequited love, but his wife, being an expert spy around her kingdom, found them and pieced them back together again?

We all love Charlotte Brontë of course, and we all love her masterly novel Villette, but in Belgium a very different view of the novel tended to be held. Claire Heger was a pillar of the Brussels commnunity and well loved for her lifelong services to education and for her charitable works. It was she, in the minds of her countrymen, who had been wronged.

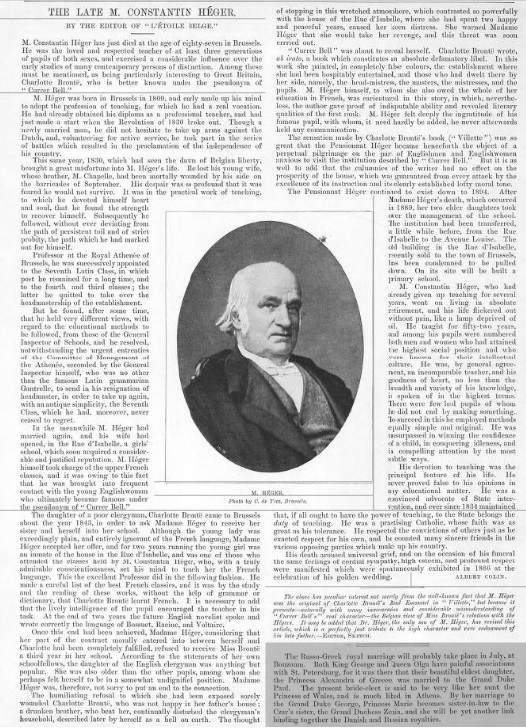

Claire Heger died in 1890, and her husband survived her by six years. On 3rd June 1896 ‘The Sketch’ carried an extraordinary obituary of Constantin Heger written by Albert Colin, editor of ‘L’Etoile Belge’. In it, Monsieur Colin writes:

‘At the end of two years [after Charlotte Brontë’s entrance into the Pensionnat], the future English novelist spoke and wrote correctly the language of Bossuet, Racine and Voltaire. Once this had been achieved, Madame Heger, considering that her part of the contract morally entered into between herself and Charlotte had been completely fulfilled, refused to receive Miss Brontë a third year in her school. According to the statements of her own schoolfellows, the daughter of the English clergyman [sic] was anything but popular… Madame Heger was, therefore, not sorry to put an end to the connection.

The humiliating refusal to which she had been exposed sorely wounded Charlotte Brontë, who was not happy in her father’s house… She warned Madame Heger that she would take her revenge, and this threat was soon carried out.’

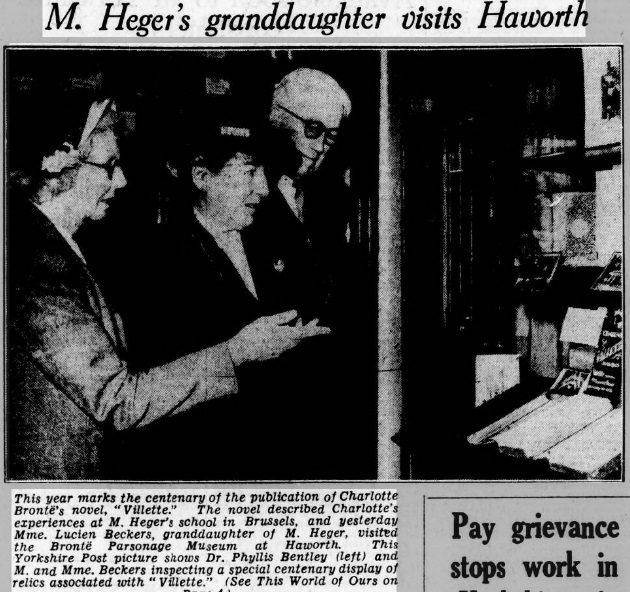

Clearly the Heger family in Brussels, maybe the city as a whole, felt slighted by Villette, although they could not help but acknowledge its genius. These wounds were healed, however, in 1953 by the visit to Haworth of a woman with a very appropriate name: Madame Beck(ers).

Madame Beckers was a guest of honour at the Brontë Parsonage, for she was in fact the granddaughter of Claire and Constantin Heger. After being given a tour of the museum, she pronounced that she forgave Charlotte for her portrayal of her grandmother as Madame Beck. What Charlotte’s response would have been we do not know, although a faint rumbling noise may have been heard coming from the nearby church.

Perhaps we too, in a spirit of reconciliation, should put aside any ill feelings we may have towards Madame Heger. At the time Charlotte knew her, Claire was successfully running two schools and raising her family, and she was also pregnant in both of the years that Charlotte was in Brussels – with Prospere in 1842 and with Julie in 1843. She may also have been understandably suspicious of Charlotte’s growing infatuation with her husband, and she may have witnessed similar things in previous years with other pupils.

What we can say for certain is that Claire Heger was a good mother and a good headmistress, and that without the advent of herself and Constantin Heger in Charlotte’s life the world of literature would be very different today. For that we can all be grateful. I will see you again next Sunday for another new Brontë blog post; have a slice of cake ready for we’ll be saying happy 201st birthday to Anne Brontë!

Wonderful insights. Recently re-reading Villette & The Professor, I can see the similarities. But it’s odd no mention of Charlotte’s sister as a character in either novel. The article written by Albert Colin (from what I could decipher) seemed plausible, even written from a man’s perspective in that era. Obviously, M. Heger and Charlotte had a mutual interest in each other. They got caught, and Heger, with too much to lose, and no doubt not that much into Charlotte, let her bear the brunt of the break-up. Indeed, not much different than today’s typical end to marital infidelities. Studying history, we learn how things change and yet remain the same.