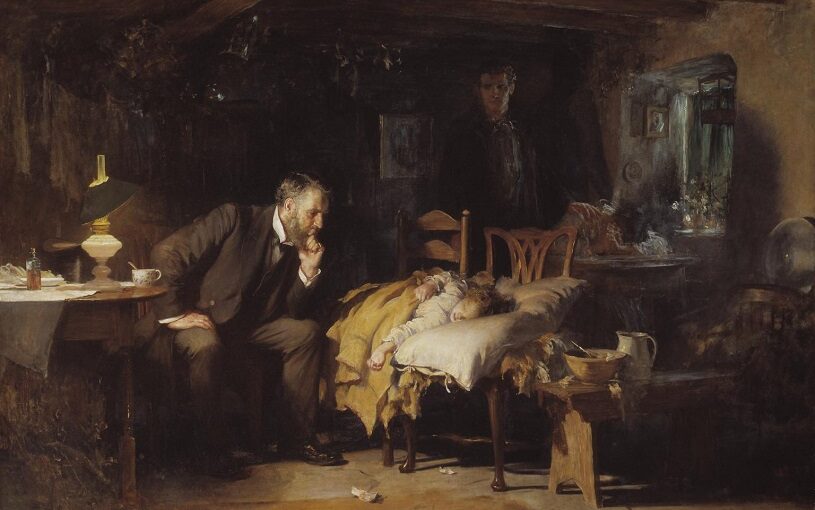

In today’s post we look at someone who was called upon by Charlotte Brontë in this week 1855, and who played a sad part in her story. Tragedy was never far away from the life of a doctor in the first half of the nineteenth century, as Dr. William MacTurk (or Macturk or McTurk) must have known well.

By the 30th of January 1855 Charlotte Brontë had been ill for some time, and her sickness and lethargy seemed to be growing worse. A Haworth doctor had already examined Charlotte and pronounced that there was little to worry about, but a worried Arthur Bell Nicholls, by then the husband of Charlotte, insisted that they call in William MacTurk for a second opinion.

We can see, then, that Dr. MacTurk must have been a very well respected physician, for his practice was based in the centre of Bradford, around nine miles distance from Haworth. He was also renowned for his philanthropic enterprises, having campaigned to lower the number of hours that children could work in factories, establishing a new church in Manningham, Bradford and being closely connected to Bradford Grammar School.

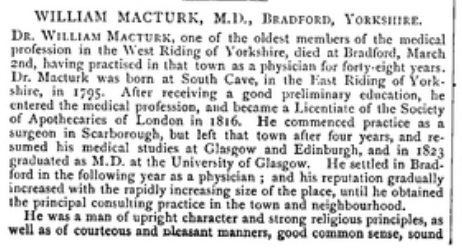

Born to Scottish parents in 1795 in South Cave, 14 miles west of Hull, he continued to practice until 1869, making him ‘one of the oldest members of the medical profession in the West Riding of Yorkshire’ as reported in a glowing obituary in an 1872 edition of the British Medical Journal. The journal also noted that MacTurk was ‘a man of upright character’, although he had ‘made no contributions to the literature of his profession’.

We can imagine how anxious Arthur Bell Nicholls and Patrick Brontë must have been on that January day 1855 as they awaited the doctor’s verdict. What it was Elizabeth Gaskell alluded to in her biography of her friend, couched in the modesty the century demanded:

‘She yielded to Mr. Nicholls’ wish that a doctor should be sent for. He came, and assigned a natural cause for her miserable indisposition; a little patience, and all would go right.’

Later the natural cause is explained more simply, ‘Martha tenderly waited on her mistress, and from time to time tried to cheer her with the thought of the baby that was coming. “I dare say I shall be glad some time,” she would say; “but I am so ill—so weary—”’

It was 166 years and a day ago, then, that Dr. MacTurk confirmed that Charlotte Brontë was pregnant. We get further evidence of this in a letter Charlotte wrote to her closest friend Ellen Nussey on 21st February 1855, in which she asks:

‘Write and tell me about Mrs. Hewitt’s case, how long she was ill and in what way.’

Mary Hewitt was a friend of Ellen, and had suffered severe sickness during her pregancy in the previous year, before giving birth to a son in December 1854. It seems clear then that Charlotte’s friends knew that she was pregnant, as further shown by the baby bonnet knitted by Charlotte’s friend, and former teacher and employer, Margaret Wooler, one of the most moving exhibits of the Brontë Parsonage Museum.

William MacTurk had diagnosed Charlotte’s pregancy but had failed to diagnose hyperemesis gravidarum, an excessive morning sickness. Today it would be treated rapidly and successfully, as in the case of the Duchess of Cambridge, but alas such knowledge and treatment was then unavailable, and Charlotte was nearing her end – who knows what a Brontë child could have achieved in their life, or if the line would still be continuing to this day.

Dr. MacTurk continued to visit Charlotte throughout her final illness, and it seems that he had also treated Branwell Brontë for the effects of his alcoholism. It could be this service which first brought him to the attention of Charlotte Brontë, leading to him featuring in her novel Shirley as the surgeon who is called upon to administer to Robert Moore:

‘”We must have Dr. Rile again, ma’am; or better still, MacTurk. He’s less of a humbug. Thomas must saddle the pony and go for him.”… Doubtless they executed the trust to the best of their ability; but something got wrong. The bandages were displaced or tampered with; great loss of blood followed. MacTurk, being summoned, came with steed afoam. He was one of those surgeons whom it is dangerous to vex – abrupt in his best moods, in his worst savage. On seeing Moore’s state he relieved his feelings by a little flowery language, with which it is not necessary to strew the present page.’

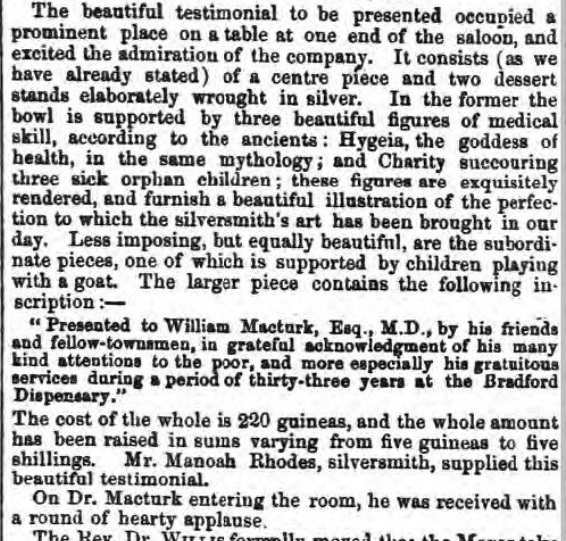

Dr. William MacTurk was much loved across Bradford and beyond, as shown by a grand testimonial thrown for him in 1859 in which he was presented with an elaborate silver bowl and stand costing over two hundred guineas, a five figure sum in today’s terms. Perhaps the greatest testimony he received, however, was being featured in a Charlotte Brontë novel. I hope you are all in good health, and I’ll see you again next Sunday for another new Brontë blog post.