March, and with it Spring, is just around the corner, and it may herald a better, more promising, time for all of us. I had thought, then, of offering up Emily Brontë’s magnificent poem ‘Hope’ for today’s blog post, but unfortunately it is a tale of hope fleeing not arriving, so it didn’t fit in with my general feeling of optimism. Instead then, with just a day left to squeeze it in, we’re going to look at the month of February in the Brontë novels:

Wuthering Heights

‘Edgar sighed; and, walking to the window, looked out towards Gimmerton Kirk. It was a misty afternoon, but the February sun shone dimly, and we could just distinguish the two fir-trees in the yard, and the sparely-scattered gravestones.

“I’ve prayed often,” he half soliloquised, “for the approach of what is coming; and now I begin to shrink, and fear it. I thought the memory of the hour I came down that glen a bridegroom would be less sweet than the anticipation that I was soon, in a few months, or, possibly, weeks, to be carried up, and laid in its lonely hollow! Ellen, I’ve been very happy with my little Cathy: through winter nights and summer days she was a living hope at my side. But I’ve been as happy musing by myself among those stones, under that old church: lying, through the long June evenings, on the green mound of her mother’s grave, and wishing – yearning for the time when I might lie beneath it. What can I do for Cathy? How must I quit her? I’d not care one moment for Linton being Heathcliff’s son; nor for his taking her from me, if he could console her for my loss. I’d not care that Heathcliff gained his ends, and triumphed in robbing me of my last blessing! But should Linton be unworthy – only a feeble tool to his father – I cannot abandon her to him! And, hard though it be to crush her buoyant spirit, I must persevere.”’

Edgar knows that Heathcliff plans to make his daughter Cathy’s life a misery by marrying her to his son Linton. His great sadness is that he knows he will be powerless to prevent this, although Nelly tries to reassure him that there is hope yet.

Jane Eyre

‘“I’m sure last winter (it was a very severe one, if you recollect, and when it did not snow, it rained and blew), not a creature but the butcher and postman came to the house, from November till February; and I really got quite melancholy with sitting night after night alone; I had Leah in to read to me sometimes; but I don’t think the poor girl liked the task much: she felt it confining. In spring and summer one got on better: sunshine and long days make such a difference; and then, just at the commencement of this autumn, little Adele Varens came and her nurse: a child makes a house alive all at once; and now you are here I shall be quite gay.”’

Mrs. Fairfax (the narrator here) has endured a lonely winter at Thornfield Hall, but with the arrival of Adele and now Jane, her isolation is over. I think we can all sympathise with Mrs. Fairfax here.

The Tenant Of Wildfell Hall

‘But sometimes, I believe, she really had some little gratification in conversing with me; and one bright February morning, during twenty minutes’ stroll along the moor, she laid aside her usual asperity and reserve, and fairly entered into conversation with me, discoursing with so much eloquence and depth of thought and feeling on a subject happily coinciding with my own ideas, and looking so beautiful withal, that I went home enchanted; and on the way (morally) started to find myself thinking that, after all, it would, perhaps, be better to spend one’s days with such a woman than with Eliza Millward; and then I (figuratively) blushed for my inconstancy.’

Gilbert is supposedly to marry Eliza, but his acquaintance with the mysterious Helen of Wildfell Hall has stirred up deeper feelings. This February stroll seems to him to mark the passing of a cold wintry alliance with Eliza into something altogether warmer and invigorating with Helen.

Villette

‘One February night – I remember it well – there came a voice near Miss Marchmont’s house, heard by every inmate, but translated, perhaps, only by one. After a calm winter, storms were ushering in the spring. I had put Miss Marchmont to bed; I sat at the fireside sewing. The wind was wailing at the windows; it had wailed all day; but, as night deepened, it took a new tone – an accent keen, piercing, almost articulate to the ear; a plaint, piteous and disconsolate to the nerves, trilled in every gust.

“Oh, hush! hush!” I said in my disturbed mind, dropping my work, and making a vain effort to stop my ears against that subtle, searching cry. I had heard that very voice ere this, and compulsory observation had forced on me a theory as to what it boded. Three times in the course of my life, events had taught me that these strange accents in the storm – this restless, hopeless cry – denote a coming state of the atmosphere unpropitious to life. Epidemic diseases, I believed, were often heralded by a gasping, sobbing, tormented, long-lamenting east wind. Hence, I inferred, arose the legend of the Banshee. I fancied, too, I had noticed – but was not philosopher enough to know whether there was any connection between the circumstances – that we often at the same time hear of disturbed volcanic action in distant parts of the world; of rivers suddenly rushing above their banks; and of strange high tides flowing furiously in on low sea-coasts. “Our globe,” I had said to myself, “seems at such periods torn and disordered; the feeble amongst us wither in her distempered breath, rushing hot from steaming volcanoes.”’

February can bring storms and howling winds, and such a night has brought to mind for Lucy the myth of the banshee – whose sorrowful wails heralds tragedy and death. Much later in the book, and with Lucy living a very different life, we find the true force of storms and the fulfilment of this omen.

Agnes Grey

‘One bright day in the last week of February, I was walking in the park, enjoying the threefold luxury of solitude, a book, and pleasant weather; for Miss Matilda had set out on her daily ride, and Miss Murray was gone in the carriage with her mamma to pay some morning calls. But it struck me that I ought to leave these selfish pleasures, and the park with its glorious canopy of bright blue sky, the west wind sounding through its yet leafless branches, the snow-wreaths still lingering in its hollows, but melting fast beneath the sun, and the graceful deer browsing on its moist herbage already assuming the freshness and verdure of spring – and go to the cottage of one Nancy Brown, a widow, whose son was at work all day in the fields, and who was afflicted with an inflammation in the eyes; which had for some time incapacitated her from reading: to her own great grief, for she was a woman of a serious, thoughtful turn of mind. I accordingly went, and found her alone, as usual, in her little, close, dark cottage, redolent of smoke and confined air, but as tidy and clean as she could make it. She was seated beside her little fire (consisting of a few red cinders and a bit of stick), busily knitting, with a small sackcloth cushion at her feet, placed for the accommodation of her gentle friend the cat, who was seated thereon, with her long tail half encircling her velvet paws, and her half-closed eyes dreamily gazing on the low, crooked fender.

“Well, Nancy, how are you to-day?”

“Why, middling, Miss, i’ myseln – my eyes is no better, but I’m a deal easier i’ my mind nor I have been,” replied she, rising to welcome me with a contented smile; which I was glad to see, for Nancy had been somewhat afflicted with religious melancholy. I congratulated her upon the change. She agreed that it was a great blessing, and expressed herself “right down thankful for it”; adding, “If it please God to spare my sight, and make me so as I can read my Bible again, I think I shall be as happy as a queen.”

“I hope He will, Nancy,” replied I; “and, meantime, I’ll come and read to you now and then, when I have a little time to spare.”

With expressions of grateful pleasure, the poor woman moved to get me a chair; but, as I saved her the trouble, she busied herself with stirring the fire, and adding a few more sticks to the decaying embers; and then, taking her well-used Bible from the shelf, dusted it carefully, and gave it me. On my asking if there was any particular part she should like me to read, she answered –

“Well, Miss Grey, if it’s all the same to you, I should like to hear that chapter in the First Epistle of St. John, that says, ‘God is love, and he that dwelleth in love dwelleth in God, and God in him.’”

With a little searching, I found these words in the fourth chapter. When I came to the seventh verse she interrupted me, and, with needless apologies for such a liberty, desired me to read it very slowly, that she might take it all in, and dwell on every word; hoping I would excuse her, as she was but a “simple body.”

“The wisest person,” I replied, “might think over each of these verses for an hour, and be all the better for it; and I would rather read them slowly than not.”

Accordingly, I finished the chapter as slowly as need be, and at the same time as impressively as I could; my auditor listened most attentively all the while, and sincerely thanked me when I had done. I sat still about half a minute to give her time to reflect upon it; when, somewhat to my surprise, she broke the pause by asking me how I liked Mr. Weston?

“I don’t know,” I replied, a little startled by the suddenness of the question; “I think he preaches very well.”

“Ay, he does so; and talks well too.”’

Agnes’ haughty young charges in the Murray family think little of the assistant curate Reverend Weston, but the poor parishioners of the area have a very different view of him. Agnes’ love for Weston is growing because of his character and actions, rather than his looks; these are the things that the author Anne Brontë prized most highly too, and which she found pleasing in both Weston and in his prototype Reverend Weightman.

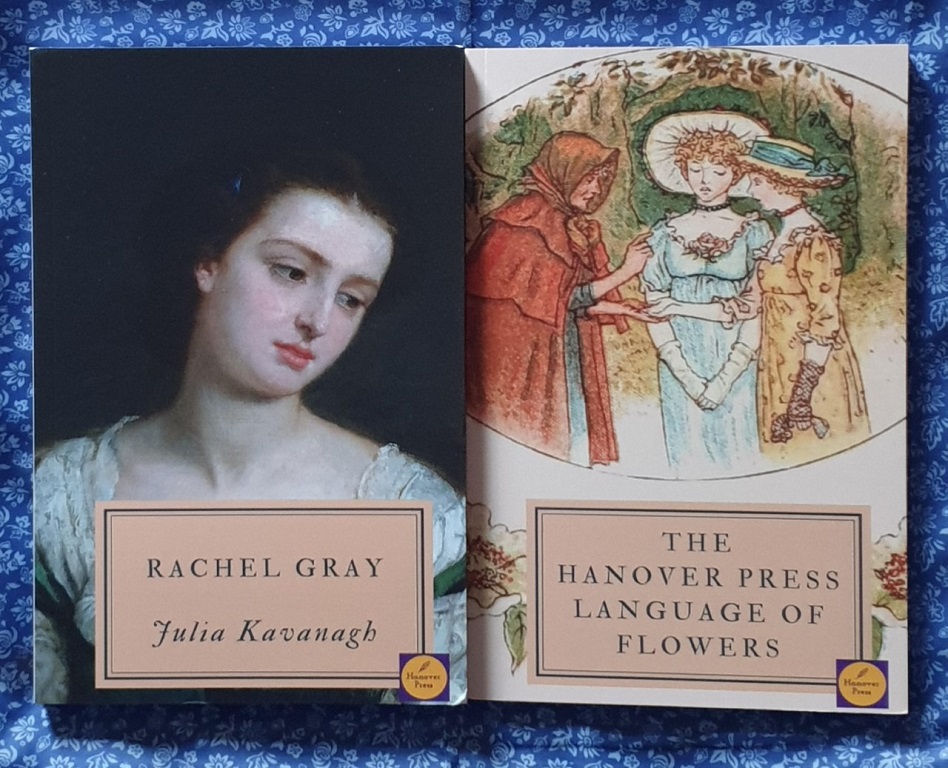

It’s a shorter post today because I’m currently preparing to post copies of my Hanover Press books Rachel Gray and The Hanover Press Book of Flowers. I’m really happy with how they’ve turned out, and I’m thrilled that more people will be able to read Julia Kavanagh’s most personal novel once more. Copies will be heading out to Kickstarter backers next week, but if you missed out on that you can pre-order now at hanoverpress.co.uk/store in readiness for its general release on March 11th.

So what do we learn from the depiction of February in the Brontë novels? It’s a time of change, a time to say goodbye to coldness in the air and coldness in our hearts. Better times are coming, it seems to say, and so we must trust to the future and wait for the warmth. I will see you again in March, i.e. next Sunday, for another new Brontë blog post.