The Brontë sisters are unique in the annals of great literature – after all, which other literary family had three siblings who all wrote great works of fiction? There are, however, some similarities between the Brontës and other writing greats – for example, whilst their juvenilia is astonishing, many other writers also created large bodies of youthful prose and poetry. John Ruskin, for one, produced his own ‘little books’, although they can’t match the power, beauty and brilliance of the tiny volumes created by the Brontë children.

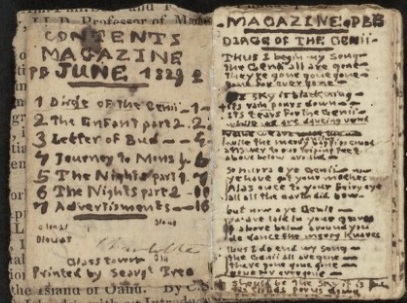

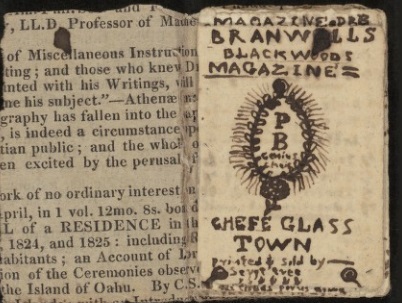

This week marks the 192nd anniversary of an especially wonderful piece of Brontë juvenilia – written by Charlotte Brontë when she was just 12 years old, and dated by her on the 12th March 1829, she entitled it simply ‘The History of the Year.’ It tells us a lot about the lives of the young Brontës at the time, so I’ve reproduced it below:

‘Once Papa lent my sister Maria a book. It was an old geography and she wrote on its blank leaf, “Papa lent me this book.” The book is an hundred and twenty years old. It is at this moment lying before me while I write this. I am in the kitchen of the parsonage house, Haworth. Tabby the servant is washing up after breakfast and Anne, my youngest sister (Maria was my eldest), is kneeling on a chair looking at some cakes which Tabby has been baking for us. Emily is in the parlour brushing it. Papa and Branwell are gone to Keighley. Aunt is up stairs in her room and I am sitting by the table writing this in the kitchin. Keighley is a small town four miles from here. Papa and Branwell are gone for the newspaper, the Leeds Intelligencer, a most excellent Tory news paper edited by Mr Edward Wood for the proprietor Mr Hernaman. We take and 2 and see three newspapers a week. We take the Leeds Intelligencer, party Tory, and the Leeds Mercury, Whig, edited by Mr Baines and his brother, son in law and his 2 sons, Edward and Talbot. We see the John Bull; it is a High Tory, very violent. Mr Driver lends us it, likewise Blackwood’s Magazine, the most amiable periodical there is. The editor is Mr Christopher North, an old man, 74 years of age. The 1st of April is his birthday. His company are Thomas Tickler, Morgan O’Doherty, Macrabin, Mordecai Mullion, Warrell, and James Hogg, a man of most extraordinary genius, a Scottish shepherd.

Our plays were established: Young Men, June 1826; Our Fellows, July 1827; Islanders, December 1827. These are our three great plays that are not kept secret. Emily’s and my bed plays were established the 1st December 1827, the others March 1828. Their nature I need not write on paper, for I think I shall always remember them. The Young Men took its rise from some wooden soldiers Branwell had, Our Fellows from Aesop’s Fables, and the Islanders from several events which happened. I will sketch out the origins of our plays more explicitly if I can. March 12, 1829.

Young Men’s

Papa brought Branwell some soldiers at Leeds. When Papa came home it was night and we were in bed, so next morning Branwell came to our door with a box of soldiers. Emily and I jumped out of bed and I snatched up one and exclaimed: “This is the Duke of Wellington! It shall be mine!” when I had said this, Emily likewise took one up and said it should be hers; when Anne came down, she said one should be hers. Mine was the prettiest of the whole, and the tallest, and the most perfect in every part. Emily’s was a grave-looking fellow, and we called him “Gravey”. Anne’s was a queer little thing, much like herself. He was called Waiting Boy. Branwell chose Bonaparte. March 12, 1829.

The origin of the O’Dears

The origin of the O’Dears was as follows. We pretended we had each a large island inhabited by people 6 miles high. The people we took out of Aesop’s Fables. Hay Man was my chief man, Boaster Branwell’s, Hunter Anne’s, and Clown Emily’s. Our chief men were 10 miles high except Emily’s who was only 4. March 12, 1829.

The origin of the Islanders

The origin of the Islanders was as follows. It was one wet night in December. We were all sitting round the fire and had been silent some time, and at last I said, ‘Suppose we each had an island of our own.’ Branwell chose the Isle of Man, Emily Isle of Arran and Bute Isle, Anne, Jersey, and I chose the Isle of Wight. We then chose who should live in our islands. The chief of Branwell’s were John Bull, Astley Cooper, Leigh Hunt, etc, etc. Emily’s Walter Scott, Mr Lockhart, Johnny Lockhart etc, etc. Anne’s Michael Sadler, Lord Bentinck, Henry Halford, etc, etc. And I chose Duke of Wellington & son, North & Co., 30 officers, Mr Abernethy, etc, etc. March 12, 1829.’

A sweet summary of a year from Charlotte, and it’s almost as if we were in that moorside parsonage with them. Even at this age, and with this brief description to examine, we get glimpses of the characters they would carry into adulthood.

Charlotte is incredibly perceptive and bright, with a great thirst for knowledge – she is clearly a voracious reader who knows not only the names of the newspaper proprietors and editors, but their birthdays; in those pre-Wikipedia days, that’s impressive knowledge. She is also taking a keen interest in politics, and in society in general.

Branwell is already cultivating a rebellious streak and a love of the anti-hero. When choosing his heroes he picks Napoleon Bonaparte, enemy of Charlotte’s beloved Duke of Wellington, and later chooses the jingoistic John Bull to man his island – perhaps inspired by the ‘very violent’ newspaper bearing this fictional character’s name.

Emily is idiosyncratic; rules are not for her, she will follow her own path – in childhood and adulthood. The O’Dears are ten miles high, but Emily’s is only four miles high, smaller than the general populace around them. The siblings pick an island each, but Emily decides that she will have two islands. There was obviously no arguing with Emily once she had made her mind up.

What do we learn of Anne? First of all we see Anne kneeling on a chair looking longingly at some cakes. Perhaps kneeling on chairs was a habit of young Anne’s, and that explains Aunt Branwell’s question to her, “Where are your feet Anne?”, in the 1834 diary paper written by Anne and Emily. I believe Anne had a fondness for cakes and all things sweet, as we have also heard a Haworth villager, a young boy at the time, say how Anne always brought him a little cake when she saw him. We also see an incredibly precocious intelligence in young Anne: in December 1827, aged 7, Anne picks as her islander Lord Bentinck, a military leader and politician.

It’s a fascinating snapshot of history; I wonder what people two hundred years hence would make of our history if we wrote a History of the Year for 2021? We’d need more than a couple of pages, that’s for sure.

Thank you for joining me today, and I look forward to seeing you next Sunday for another new Brontë blog post. It’s a special day in the United Kingdom: Mother’s Day. To all the mothers and grandmothers out there, have a great day. Let’s also remember today the Brontës’ own mother – Maria Brontë, nee Branwell.

So interesting.