This weekend, the 27th of March to be precise, saw the advent of World Theatre Day. I love the theatre, and we know that Charlotte, at least, did too, so this week we’re going to look at theatre and the Brontës.

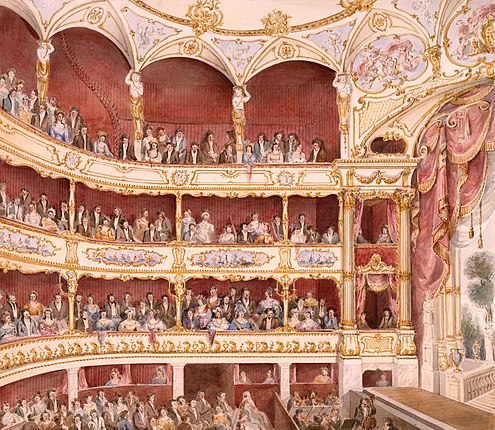

At the time of the Brontës theatres were not yet the mass entertainment centres they were to become during the twentieth century; the working class had neither the time nor money to attend them, and the transport infrastructure was only just appearing that would make it easy for theatre goers to reach the towns and cities that had a theatre. Attending the theatre was an upper class activity and an occasional treat to be savoured for middle class families like the Brontes, but we have records of two such occasions when Charlotte Brontë was in the audience.

Firstly, let us turn to an account given many years later by a Frank Peel of an encounter with Charlotte Brontë sometime in the early 1850s. Out of work and down on his luck, Peel had been promised a job in a travelling theatre show, but he had no shoes in which to attend an interview. Having been told of Charlotte’s reputation for philanthropy he made his way to the parsonage and, after reciting some Shakespeare which was rather less than well received, Frank was given a pair of boots which had belonged to Branwell along with advice to give up thoughts of a stage career. Nevertheless, Frank Peel obtained a job as a stage hand and general factotum, which leads us to this revelation:

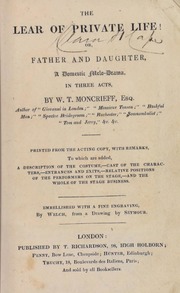

‘I did go behind the scenes at night, and I am now getting at what I wish to tell you. The play was called ‘The Lear of Private Life’ – that is, a sort of domestic copy of ‘King Lear.’ I assisted in shifting the scenes, and before the last act began the ‘Lear’ sent me to the money-taker to get a shilling and fetch him some brandy in a pint-pot, for he was “nearly a croaker.” It was a ‘grand fashionable night,’ and there were about a hundred people in the pit, and in coming from the stage to the side-door I had to pass on one side to it, and there, only just within the garden enclosure, and close to where I had to pass, was Miss Brontë and the other lady I had seen the day before at Haworth parsonage! I now felt so guilty of having told Miss Brontë a falsehood about having got the engagement that I should not have ventured to pass her if the actor’s words “nearly a croaker” had not rung in my ears. In the walk for the brandy I had time to collect myself, and I decided to walk past the ladies as if I belonged to the establishment. I did so, and also made a very respectful bow to them, which they gracefully returned. I looked through the peep-hole in the wing and saw them leave soon after. It was some years after this before I learned that the lady who had given me the breakfast, the boots, and the scolding was the authoress of Jane Eyre. I was pleased the rascal stole my boots when I learnt I had had an interview with Charlotte Brontë.’

From this account we can tell that Charlotte Brontë, along with a companion whom we can assume to be Ellen Nussey on one of her visits to the parsonage, had travelled from Haworth to Keighley to see a play – perhaps this is something she was in the habit of doing, and perhaps Anne and Emily had shared that experience in happier times too?

We now come to an account from Charlotte Brontë herself, and of an altogether grander theatrical performance. In June 1851, Charlotte was in London where she visited the St. James Theatre on 7 June and saw a production of ‘Adrienne Lecouvrer’ – its chief attraction was that it starred the most famous, and infamous, actress of the day – Elisa Felix, known across Europe by her stage name of Rachel. Felix had risen from humble beginnings to become a hugely acclaimed, if melodramatic, actress, and she was also the mistress of a number of the leading figures in French society, including Emperor Napoleon III. Charlotte was so taken by Rachel’s performance that she returned to the same theatre to see her in Corneille’s ‘Horace’ two weeks later, and she gave fulsome descriptions of the actress in three letters. On 11th June 1851, Charlotte wrote to Amelia Ringrose:

‘I have seen Rachel – her acting was something apart from any other acting it has come in my way to witness; her soul was in it – and a strange soul she has. I shall not discuss it – it is my hope to see her again.’

See her again, and discuss her again, Charlotte did, for on the 24th of June she wrote to Ellen Nussey:

‘On Saturday I went to see & hear Rachel – a wonderful sight – terrible as if the earth had cracked deep at your feet and revealed a glimpse of hell. I shall never forget it – she made me shudder to the marrow of my bones; in her some fiend has certainly taken up an incarnate home. She is not a woman – she is a snake – she is the -’

Mademoiselle Rachel’s performances had certainly made a deep impression on Charlotte, so much so that she she was still telling people about them five months later. On 15th November 1851 she wrote to Joe Taylor:

‘Rachel’s Acting (sic) transfixed me with wonder, enchained me with interest and thrilled me with horror. The tremendous power with which she expresses the very worst passions in their strongest essence forms an exhibition as exciting as the bull-fights of Spain and the gladiatorial combats of old Rome – and (it seemed to me) not one whit more moral than these poisoned stimulants to popular ferocity. It is scarcely human nature that she shews you; it is something wilder and worse; the feelings and fury of a fiend. The great gift of Genius she undoubtedly has – but – I fear – she rather abuses than turns it to good account.’

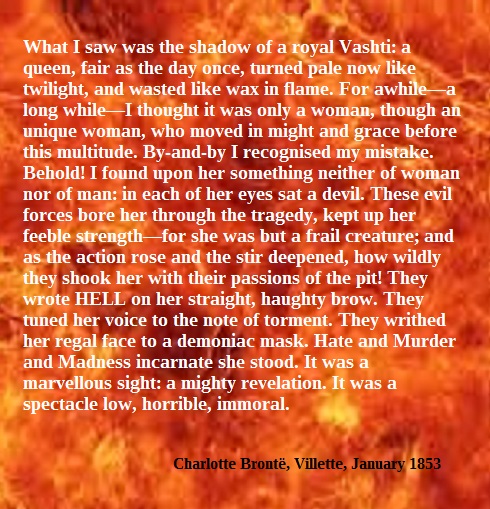

If only we could see one of Rachel’s performances today – they certainly sound like something to behold. Charlotte wasn’t finished with her yet, for she clearly uses her memories of Rachel’s performances and immortalises her as the wild, hypnotic actress performing Vashti in Villette:

There can be no doubt at all then that Charlotte Brontë was passionate about the theatre, and the work of Charlotte and her sisters has inspired many plays and performances in the decades since their passing – from stage adaptations of their work, to dramatic biopics of their lives.

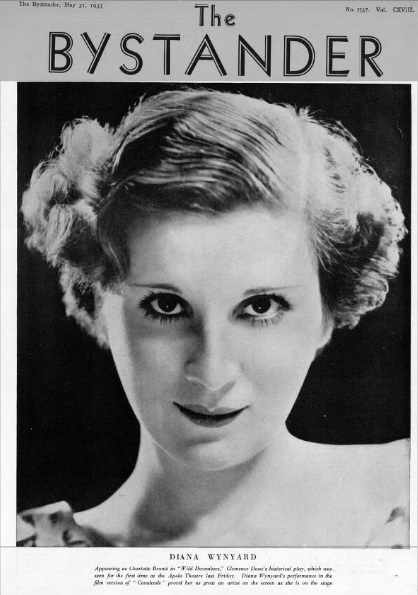

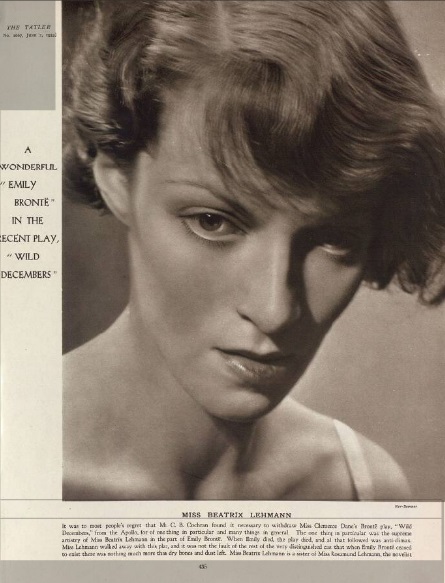

So popular were plays about the Brontës (something which continues to this day on both stage and screen) that 1933 saw two plays about the Brontës open at neighbouring theatres. One of which, ‘Wild Decembers’ by Clemence Dane was covered extensively by The Tatler and other magazines of the time, and it’s from Tatler that we get these remarkable pictures above of the opening night. In attendance are Dodie Smith, author of The Hundred and One Dalmations and I Capture The Castle, and ‘Brontë descendants’ Charlotte Brontë Branwell and her son David, members in fact of the Branwell family of Penzance.

Hopefully it won’t be too long until theatres of all sizes open their doors again, and we should all get along and support them if we can. Hopefully also there will be lots of Brontë related plays to watch. Those who live in the south may be able to see the acclaimed play ‘Bronte’ by William Luce, an award winner upon its release in 1979, as actress Bethany Goodman is currently raising funds to bring a new production to the stage this autumn. You can find more about that excellent endeavour, and back it if you so wish, at this link: https://www.justgiving.com/crowdfunding/bronte-aukdebut

It’s a pity that the Brontës themselves never wrote for the stage, as their work is wonderfully dramatic – just imagine what Mademoiselle Rachel could have brought to the part of Catherine Earnshaw! I will see you again next Sunday for another new Brontë blog post.

Such an interesting post.

I do my nutcracker performance there and I love it so much and it is so cool in there I love it